After reviewing almost 30 years of signals, University of California Berkeley researchers have identified 100 mysterious, deep-space radio blips they want to review for signs of extraterrestrial life. And they couldn’t have done it without 11 years of volunteer work from millions of PC owners around the world.

What is SETI@home?

Even with today’s advanced computers, the world’s most complex data problems can’t be solved by a single machine. Instead, it’s far more efficient to break up tasks among many separate computers. For decades, however, the technology to handle even these distributed responsibilities was relegated to well-funded companies and government institutions. But with the rise of personal computers (PCs), UC Berkeley researchers like David Gedye and David Anderson realized that the untapped pool of citizen scientists could be a vital asset. And what bigger data pool was there to draw from than the vastness of interstellar space?

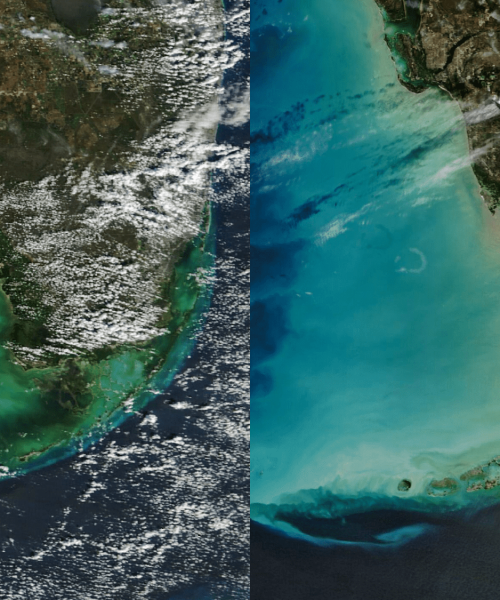

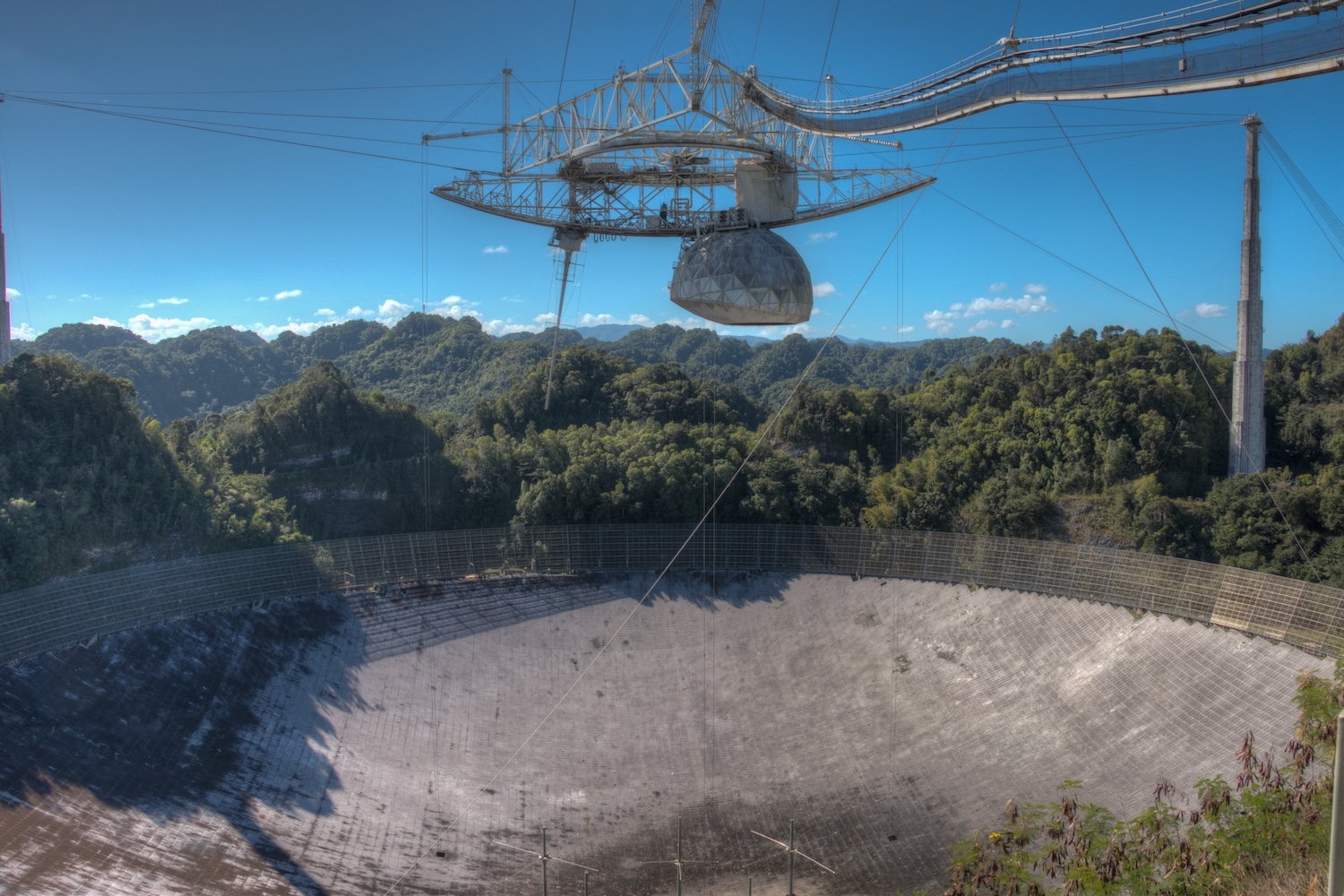

In 1999, the computer scientists teamed with astronomers Eric Korpela and Dan Werthimer to launch SETI@home. The project relied on individuals downloading a client program to their home PC designed to parse data passively collected by a 984-foot-wide radio telescope at the now-shuttered Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico. Although Arecibo’s line of sight only encompassed about a third of the entire sky, that still included most stars in the Milky Way galaxy.

“We [were], without doubt, the most sensitive narrow-band search of large portions of the sky, so we had the best chance of finding something,” Korpela said in a recent UC Berkeley profile.

Before launching SETI@home, project organizers estimated they’d receive around 50,000 volunteers. In only a few days, they surpassed 200,000 participants from over 100 countries. By the program’s one-year anniversary, the SETI@home client had been downloaded onto over 2 million PCs.

Looking for ET

The data itself wasn’t collected by simply aiming Arecibo at a section of space and listening for ET whisperings. Earth is constantly moving around the sun, and the same likely goes for any source of alien life. This required Korpela and colleagues to design a protocol to mathematically reconfigure frequency clips to account for any Doppler drifts.

“We actually had to look at a whole range of possible drift rates—tens of thousands—just to make sure that we got all possibilities. That multiplies the amount of computing power we need by 10,000,” said Anderson. “The fact that we had a million home computers available to us let us do that. No other radio SETI project has been able to do that.”

By the time SETI@home officially ended in 2020, the team was staring down around 12 billion signals of interest. Combing through those files ultimately required enlisting the help of a supercomputer—in this case an installation at Germany’s Max Planck Institute for Gravitational Physics. From there, researchers could winnow down their suspects to a couple million signals, then rank them by likelihood of ET origin after accounting for radio frequency interferences from sources like orbital satellites, TV broadcasts, and even kitchen microwaves.

Korpela and Werthimer eventually settled on about 100 final contenders worth additional examinations. Since July 2025, they have used China’s Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope (FAST) to collect new data from these sections of sky. The approach was detailed in two studies published last year in The Astronomical Journal, and showcases both the project’s highlights and places where future endeavors can improve on their work.

“Some of our conclusions are that the project didn’t completely work the way we thought it was going to. And we have a long list of things that we would have done differently and that future sky survey projects should do differently,” explained Anderson. “[But] if we don’t find ET, what we can say is that we established a new sensitivity level. If there were a signal above a certain power, we would have found it.”

The power of crowdsourcing

However, Anderson and the others aren’t holding their breath. According to Korpela, Arecibo’s limited field-of-view and a lack of any particularly striking radio blips so far means a sudden ET revelation isn’t likely just yet.

“There’s a little disappointment that we didn’t see anything,” he said. “In order to probe farther distances, you need bigger telescopes and longer observing times. It’s always best if you are able to control the telescope for your project. We weren’t able to control what the telescope was doing.”

Regardless, SETI@home speaks to the power of both crowdsourcing and citizen science. When combined with all of the PC advancements since 1999, there’s a chance that an heir to the project may finally find that extraordinary, history-altering space signal.

“I think it still captures people’s imagination to look for extraterrestrial intelligence,” said Korpella. “I think that you could still get significantly more processing power than we used for SETI@home and process more data because of a wider internet bandwidth.”