This month marks the 40th anniversary of the Commodore Amiga’s release. Alongside contemporaries like the Macintosh and Acorn desktop computers, the Amiga helped usher the digital era into homes and played a major role in the PC revolution. Originally billed as a versatile, business-oriented machine, the Amiga 1000 featured a 16/32-bit Motorola 68000 CPU, some of the most cutting-edge graphics and sound systems of the time, and a multitasking operating system running on 256 KB of ROM. The Amiga line became known for its creative capacities, including its abilities to help craft video games, artwork, and music.

The Aminga’s cultural impact was bolstered by its flashy public debut celebration, which emerged as one of the most surreal moments in tech history. On July 23, 1984, Commodore hosted a black-tie launch event in New York City at Lincoln Center, complete with an orchestra and live hardware demonstrations. The event also included a live art session with Andy Warhol, who used the Amiga to paint a portrait of Blondie frontwoman Debbie Harry.

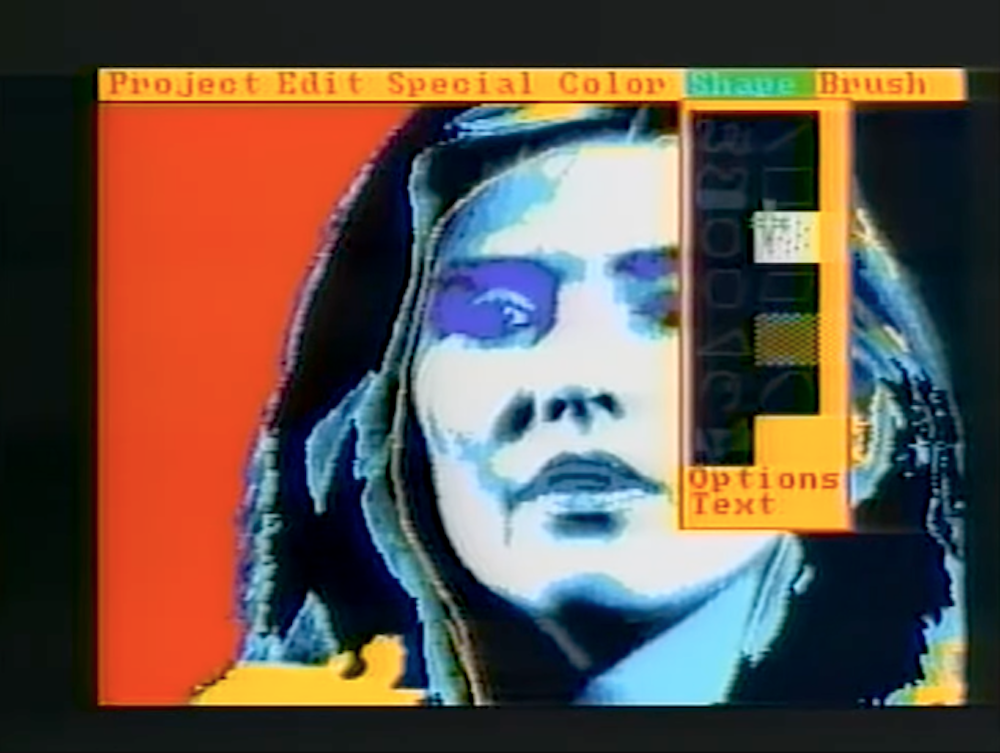

After some initial guidance from “resident Amiga artist” Jack Haeger, Warhol began by taking a “digital snapshot” of Harry before overlaying it with color fills using Amiga’s ProPaint V27 software—a precursor to illustration programs like MSPaint.

“You found it to be spontaneous?” Haeger prods Warhol at the demo’s outset.

“Yeah it’s great. It’s such a great thing,” Warhol responded flatly as onlookers laughed.

The recording of Warhol’s portrait session is only a few minutes long, but it marked the beginning of a brand ambassadorship that lasted until the artist’s death in 1987. In 1985, Commodore gifted an Amiga 1000 to Warhol, which he used to craft a series of virtual drawings including variations on his famous Campbell’s soup can series, Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus, and flowers.

In an interview with the magazine Amiga World the following year, Warhol elaborated more on his interest in the dawn of digital art.

“The thing I like most about doing this kind of work on the Amiga is that it looks like my work in other media,” he said at the time. When asked about his thoughts on how computers would affect “mass art as opposed to high art,” Warhol—true to fashion—made sure to stipulate that “mass art is high art.”

Although believed lost for decades, in 2014 the Andy Warhol Museum announced the rediscovery of multiple experimental Amiga projects stored on floppy disks in the museum’s archives.

“In the images, we see a mature artist who had spent about 50 years developing a specific hand-to-eye coordination now suddenly grappling with the bizarre new sensation of a mouse in his palm held several inches from the screen,” the museum’s chief archivist Matt Wrbican said at the time. “No doubt he resisted the urge to physically touch the screen–it had to be enormously frustrating, but it also marked a huge transformation in our culture.”

“Do you think it will push the artists? Do you think that people will be inclined to use all the different components of the art, music, video, etc.?” Amiga World editor-in-chief Guy Wright asked during the 1986 interview.

“That’s the best part about it. I guess you can… An artist can really do the whole thing,” Warhol responded. “Actually, he can make a film with everything on it, music and sound and art… everything.”