Geologists have discovered 10 new species of trilobite in a relatively unstudied area of Thailand. These extinct sea creatures were hidden for 490 million years and are helping scientists create a new map of the animal life during the late Cambrian period. They are described in a monograph that was published in October in the journal Papers in Palaeontology.

[Related: These ancient trilobites are forever frozen in a conga line.]

Trilobites were marine arthropods similar to today’s spiders and crustaceans and are known for a wide variety of body designs. A species called Walliserops may have jousted with ‘tridents’ on their heads to win mates and recent trilobite specimens have been found with full stomachs. More than 20,000 species lived in Earth’s seas before they went extinct about 250 million years ago.

The trilobite fossils described in the new paper were trapped between layers of petrified ash in sandstone and were the product of old volcanic eruptions. The sediment from the eruptions settled on the bottom of the sea and formed a green layer called a tuff. This important layer contains crystals of a critical mineral that formed during the eruption called zircon. Aside from being as tough as steel, zircon is chemically stable and heat and weather resistant. Zircon also persists while the minerals in other kinds of rocks erode over time. Individual atoms of uranium that transform into lead live inside these resilient zircon crystals and give paleontologists a benchmark for dating the fossils.

“We can use radio isotope techniques to date when the zircon formed and thus find the age of the eruption, as well as the fossil,” study co-author and University of California, Riverside geologist Nigel Hughes said in a statement.

Finding tuffs from the late Cambrian period (between 497 and 485 million years ago) is also rather rare. According to the team, it is one of the “worst dated” intervals of time in Earth’s history.

“The tuffs will allow us to not only determine the age of the fossils we found in Thailand, but to better understand parts of the world like China, Australia, and even North America where similar fossils have been found in rocks that cannot be dated,” study co-author and Texas State University geologist Shelly Wernette said in a statement. Wernette previously worked in the Hughes Lab.

The trilobite fossils were found on the coast of an island called Ko Tarutao. This island is part of a UNESCO geopark site that has encouraged international teams of scientists to work in this area.

One of the most interesting discoveries was 12 types of trilobites that scientists have seen in other parts of the world, but not in Thailand.

“We can now connect Thailand to parts of Australia, a really exciting discovery,” said Wernette.

During trilobites’ lifetime, this area was located on the margins of an ancient supercontinent called Gondwanaland. The giant land mass included present day India, Africa, South America, Australia, and Antarctica.

[Related: Ancient ‘weird shrimp from Canada’ used bizarre appendages to scarf up soft prey.]

“Because continents shift over time, part of our job has been to work out where this region of Thailand was in relation to the rest of Gondwanaland,” Hughes said. “It’s a moving, shape shifting, 3D jigsaw puzzle we’re trying to put together. This discovery will help us do that.”

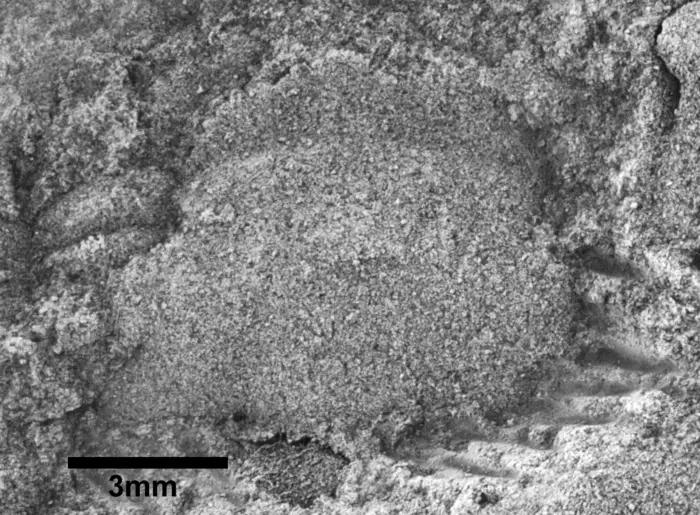

They named one of the newly discovered species Tsinania sirindhornae in honor of Thai Royal Princess Maha Chakri Sirindhorn, for her dedication to developing the sciences in Thailand.

“I also thought this species had a regal quality. It has a broad headdress and clean sweeping lines,” Wernette said.

If the team can get an accurate date from the tuffs that the remains of T. sirindhornae had been sitting in for millions of years, they could be able to determine if closely related species found in northern and southern China are roughly the same age.

The team believes that the portrait of the ancient world hidden in these trilobite fossils contain invaluable information about our planet’s history.

“What we have here is a chronicle of evolutionary change accompanied by extinctions. The Earth has written this record for us, and we’re fortunate to have it,” Hughes said. “The more we learn from it the better prepared we are for the challenges we’re engineering on the planet for ourselves today.”