An unusual jellyfish species found in the eastern Pacific Ocean called Cladonema pacificum is only about the size of a pinkie nail, but it can regenerate an amputated tentacle in just two or three days. Jellyfish need their tentacles to hunt and feed, so keeping them intact is crucial to their survival. How jellyfish form the parts necessary to regrow appendages has been a mystery. Now, a team based in Japan is beginning to understand the cellular processes that these tiny jellyfish use in limb regeneration. The findings are described in a study published December 21 in the journal PLOS Biology.

[Related: Even without brains, jellyfish learn from their mistakes.]

Finding the blastema

Salamanders and insects like beetles form a clump of undifferentiated cells that have not developed into specific cell types yet. These undifferentiated cells can grow into a blastema, which is critical for repairing damage and regrowing appendages.

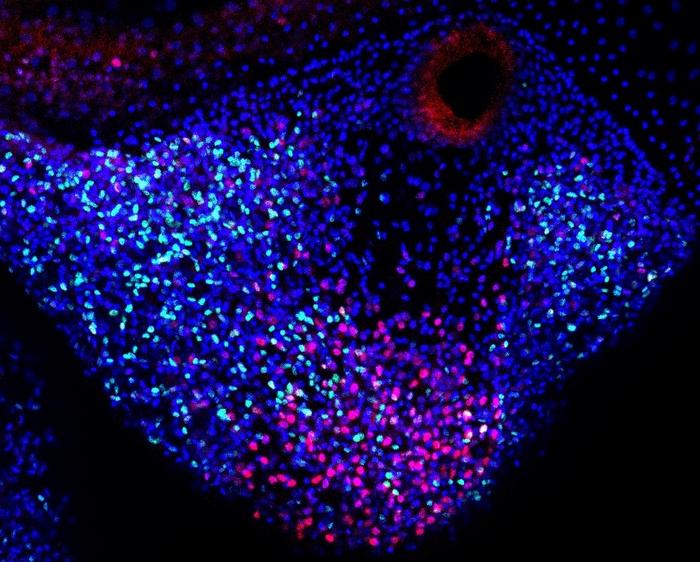

To look for signs of the crucial blastema in jellyfish, the authors of this study amputated a tentacle from a Cladonema pacificum jellyfish in the lab. They then studied the cells that were growing in the jellyfish post-amputation. The team found that jellyfish have stem-like proliferative cells actively growing and dividing, but are not yet changing into specific cell types. These cells appear at the site of injury and help from the blastema.

“Importantly, these stem-like proliferative cells in blastema are different from the resident stem cells localized in the tentacle,” study co-author and University of Tokyo cell biologist Yuichiro Nakajima said in a statement. “Repair-specific proliferative cells mainly contribute to the epithelium—the thin outer layer—of the newly formed tentacle.”

These resident stem-like cells near the jellyfish’s tentacle are responsible for maintaining and repairing whatever cells the jellyfish needs throughout its life. However, the proliferative cells needed to repair a missing appendage only appear when the jellyfish is injured.

“Together, resident stem cells and repair-specific proliferative cells allow rapid regeneration of the functional tentacle within a few days,” Nakajima said.

Bilaterians vs. non-bilaterians

According to the authors, this finding helps researchers better understand how blastema formation differs among different animal groups who have different developmental shapes. For example, salamanders are bilaterian animals that develop two equal sides on the right and left. Jellyfish are considered non-bilaterians, but both jellyfish and salamanders are capable of regenerating limbs despite their symmetrical differences. Salamander limbs have stem cells restricted to specific cell-type needs and this process appears to operate similarly to the repair-specific cells the team observed in jellyfish.

[Related: There’s no stopping this immortal jellyfish.]

“Given that repair-specific proliferative cells are analogues to the restricted stem cells in bilaterian salamander limbs, we can surmise that blastema formation by repair-specific proliferative cells is a common feature independently acquired for complex organ and appendage regeneration during animal evolution,” University of Tokyo cell biologist Sosuke Fujita said in a statement.

It is still unclear where the repair-specific proliferative cells observed in the blastema originate. The research tools that are currently available to investigate these cellular origins are too limited to explain the source of these cells or find other stem-like cells. More study and new tools for studying genetics are needed.

“It would be essential to introduce genetic tools that allow the tracing of specific cell lineages and the manipulation in Cladonema,” Nakajima said. “Ultimately, understanding blastema formation mechanisms in regenerative animals, including jellyfish, may help us identify cellular and molecular components that improve our own regenerative abilities.”