New deep sea sonar scans are reigniting interest in one of the 20th century’s most enduring mysteries—the disappearance of Amelia Earhart. For those in charge of maintaining the world’s largest Earhart archival collection, last week’s news appears not only credible, but extremely promising.

“The potential discovery of the location of Amelia Earhart’s plane is incredibly exciting,” Sammie Morris, Purdue University’s Head of Archives and Special Collections, tells PopSci. Earhart joined Purdue’s faculty in 1935 as an aeronautics adviser and counselor in the study of careers for women. “The location of the found object is in the vicinity of where the plane may logically have gone down when the fliers were en route to Howland Island, and the imagery the searchers captured is compelling and appears consistent with the shape of a plane.”

[Related: Many have tried, but no one has solved the mystery of Amelia Earhart’s demise.]

Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, disappeared on July 2, 1937, during her widely covered attempt to become the first female pilot to circumnavigate the world. Countless experts, researchers, and fame-seekers attempted to locate the legendary pilot’s final resting place over the next 87 years—spawning all manner of plausible and not-so-plausible theories in the process.

In 2018, for example, an investigation team claimed to possess proof Earhart that crash landed on Gardner Island, approximately 350 nautical miles from Howland Island, where the aviator was expected to land for refueling. Subsequent examinations proved inconclusive, leading groups like the marine robotics company, Deep Sea Vision, to continue the decades’ long quest.

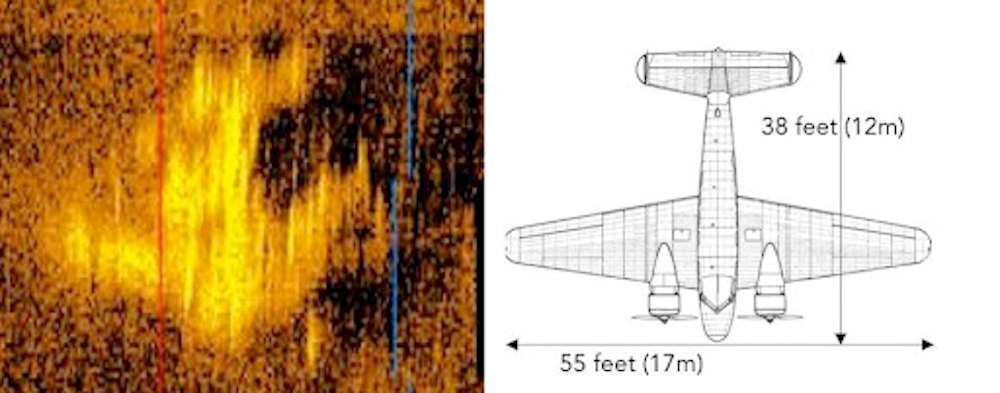

Last Friday, the organization released striking sonar imagery “captured westward of Earhart’s projected landing point” in the Pacific Ocean. According to DSV’s announcement, the scan appears to show “unique dual tails” emblematic to the famed pilot’s dual-engine Lockheed 10-E Electra. Further analysis also indicates the anomaly’s size appears to match the dimensions of Earhart’s aircraft.

Although exact coordinates remain secret to guard the potential find, Deep Sea Vision CEO Tony Romeo told The Wall Street Journal on January 26 that the sonar imaging was obtained from a high-tech submersible exploring a region 16,000 feet underwater, within 100 miles of Howland Island.

“We always felt that [Earhart] would have made every attempt to land the aircraft gently on the water, and the aircraft signature that we see in the sonar image suggests that may be the case,” the pilot and former US. Air Force intelligence officer said in an official press release.

To search for Earhart’s plane, Romeo’s team subscribed to what’s known as the “Date Line Theory” first posited in 2010 by Liz Smith, an amateur pilot and former NASA employee. According to Smith, Earhart’s crash can likely be attributed to navigator Fred Noonan forgetting to set the plane’s calendar back one day from July 3 to July 2 after flying over the International Date Line. Romeo and collaborators believed such an error could easily be made after the duo’s previous 17 hours of flying, and concentrated their search while taking a potential westward navigational error of 60 miles into question.

Over roughly three months, DSV’s HUGIN 6000 autonomous underwater submersible combed across a cumulative 5,200 square miles of Pacific Ocean floor using a modified side scan sonar capable of imaging 1,600-meter-wide chunks at a time. Normal side scan sonars, by comparison, only handle 450 meters per scan.

Of course, nothing can be fully confirmed until a team returns to the site to obtain verifiable evidence of Earhart’s 10-E Electra. Until then, archivists at Purdue University are thrilled at the mystery’s potential conclusion.

“We [are] eagerly following the story along with the rest of the world as it develops,” Morris tells PopSci. “Due to the close ties Earhart had with Purdue we have a particular interest in learning the outcome of this exciting discovery.”