It’s the fastest-growing black hole ever recorded. Quasar J0529-4351 eats the equivalent of the energy in our sun every single day. It is also roughly 17 billion times bigger than our sun. This ravenous star-gobbling hole is described in a study published February 19 in the journal Nature Astronomy and its size could help piece together the universe’s history.

[Related: Blindingly bright black holes could help cosmologists see deeper into the universe’s past.]

“The incredible rate of growth also means a huge release of light and heat,” study co-author and astronomer at The Australian National University (ANU) Christian Wolf said in a statement. “So, this is also the most luminous known object in the universe. It’s 500 trillion times brighter than our sun.”

What are quasars?

Quasars are galaxies with an active and energetic core that is powered by black holes. They typically offer astronomers a different view of black hole, showing energetic jets beaming out from two sides. A quasar’s dark center gobbles up the matter that is nearby and then smushes that material into an incredibly hot disc. This matter is then shot out over huge distances. However, it takes billions of years for their light to be visible on Earth. This means astronomers can view these black holes as they existed billions of years ago.

Quasars are still quite mysterious, but some more recent studies have found that quasars may shine consistently enough for astronomers to use them to fill in gaps in cosmic history. J0529-4351’s unprecedented brightness and size could help further this study of the universe’s early days.

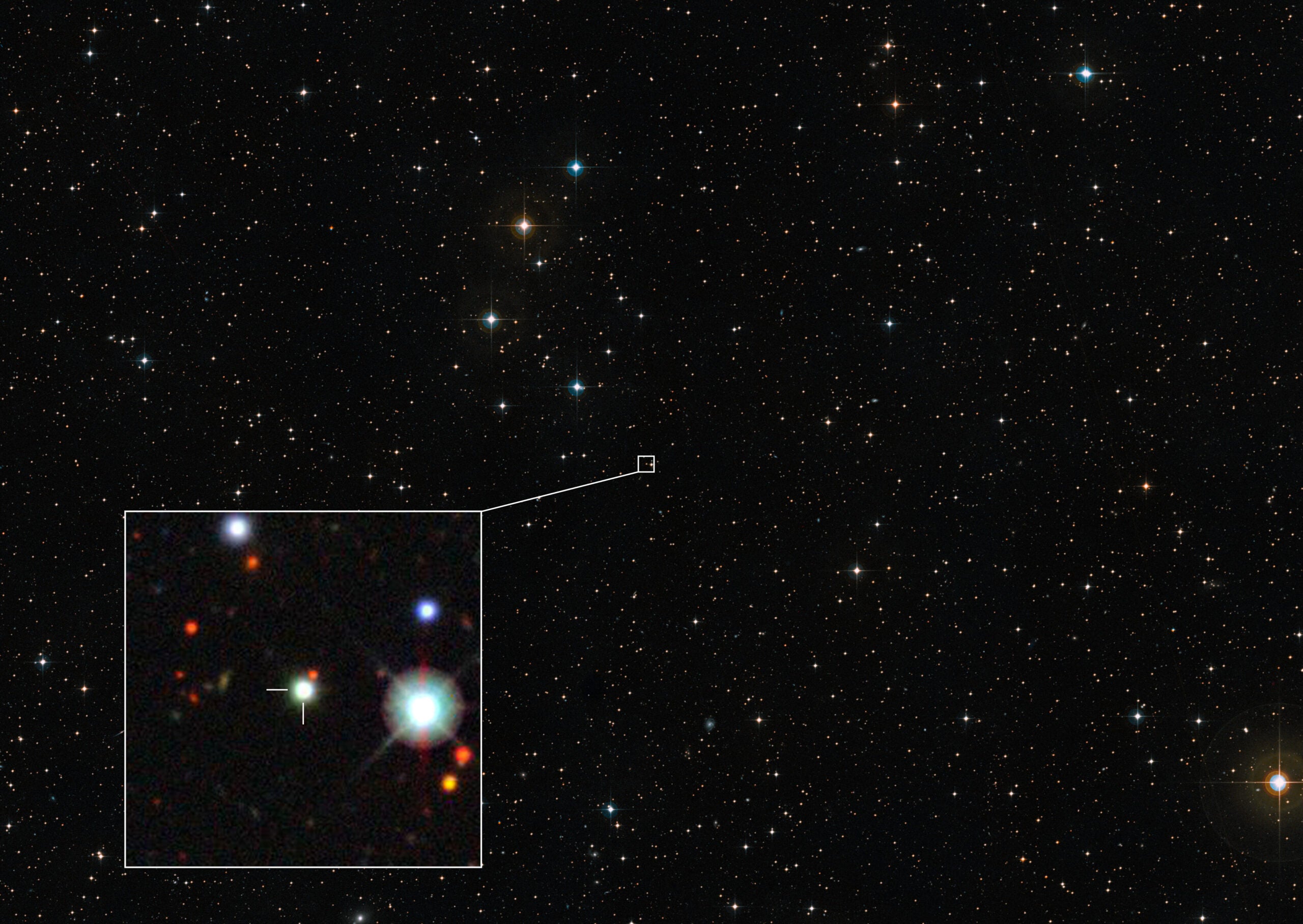

“It’s a surprise it remained undetected until now, given what we know about many other, less impressive black holes. It was hiding in plain sight,” study co-author and ANU astronomer Christopher Onken said in a statement.

A big black hole meets the Very Large Telescope

J0529-4351 has a mass that is roughly 17 billion times that of our solar system’s sun. It was detected with ANU’s Siding Spring Observatory’s telescope, but confirming such a massive black hole requires the help of an even bigger telescope. The team turned to the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile. With four telescopes 27 feet in diameter, it is one of the largest telescopes on Earth. They used it to confirm the full nature of the black hole and measure its mass.

“The light from this black hole has traveled over 12 billion years to reach us,” study co-author and University of Melbourne astrophysicist Rachel Webster said in a statement. “In the adolescent universe, matter was moving chaotically and feeding hungry black holes. Today, stars are moving orderly at safe distances and only rarely plunge into black holes.”

[Related: What we can learn from baby black holes.]

The intense radiation is coming from the accretion disc around the black hole and creates a holding pattern for all the cosmic material waiting to be consumed. According to the team, it looks like a large storm cell with temperatures over 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The region has cosmic winds that are blowing so fast that they would go around the Earth in one second.

Approaching a limit?

The accretion disc is about seven light years in diameter—or roughly 42 trillion Earth miles. According to the team, this makes it the largest known accretion disc in the universe.

The team believes that the black hole could be approaching the Eddington mass limit. This is the proposed upper limit of the mass of a star or an accreditation disc. More research and observations are needed to get a better idea of its growth rate.

When the quasar was first detected in 1980, astronomers believed it was a star. It was reclassified in 2023 after more detailed observations were taken in Chile and Australia.

“The exciting thing about this quasar is that it was hiding in plain sight and was misclassified as a star previously,” Yale University astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan told Sky News. Natarajan was not involved in the study.