One of NASA’s Great Observatories may soon meet an untimely demise. The Chandra X-Ray Observatory—an orbiting telescope launched in 1999 aboard Space Shuttle Columbia—is facing a major financial threat in NASA’s latest budget proposal. Major cuts to its funding could lead to layoffs for half of the observatory’s staff by October and, according to concerned scientists, a premature end to the mission around 2026. Astronomers are worried that losing a telescope so crucial to our studies of the high-energy cosmos could set the field back by decades.

In an open letter, a group of astronomers claimed that Chandra “is capable of many more years of operation and scientific discovery” and that a “reduction of the budget of our flagship X-ray mission will have an outsized impact on both U.S. high-energy astrophysics research and the larger astronomy and astrophysics community.”

“It’s a huge monetary and environmental toll to put an observatory up in space, so I think it’s really important to value that and to not treat these instruments as disposable,” adds Samantha Wong, an astronomer at McGill University. “People outside of astronomy contribute to the cost of these instruments (both literally and in terms of environmental and satellite pollution), so it’s in everyone’s best interest that we use Chandra to the full extent it’s capable of.”

Chandra was launched in the 90s along with the optical and ultraviolet Hubble Space Telescope, the infrared Spitzer Space Telescope (recently decommissioned in 2020), and the Compton Gamma Ray Observatory (the shortest lived of the bunch, ending in 2000). Much like the powerhouse Hubble, Chandra was initially meant to operate for five years—but its enduring excellent performance has cemented it as a pillar of astronomy research for the past two and a half decades. Although any piece of equipment will naturally degrade over time, Chandra continues to return excellent scientific results, deemed “the most powerful X-ray facility in orbit” from a recent NASA senior review, with potential to keep going for another decade until it runs out of fuel as long as the team on the ground can continue operating it.

Space telescopes are huge endeavors and marvels of engineering, and each one opens up a new window to the universe. Astronomy requires seeing the universe in multiple wavelengths of light, far beyond what human eyes can sense, from low-energy radio waves to the highest-energy gamma rays. “It’s hard to overstate how much we’re learning about the cosmos by just putting big pieces of glass in the sky,” said Harvard astronomer Grant Tremblay in a conversation with New York Rep. Joe Morelle.

[ Related: Where do all those colors in space telescope images come from? ]

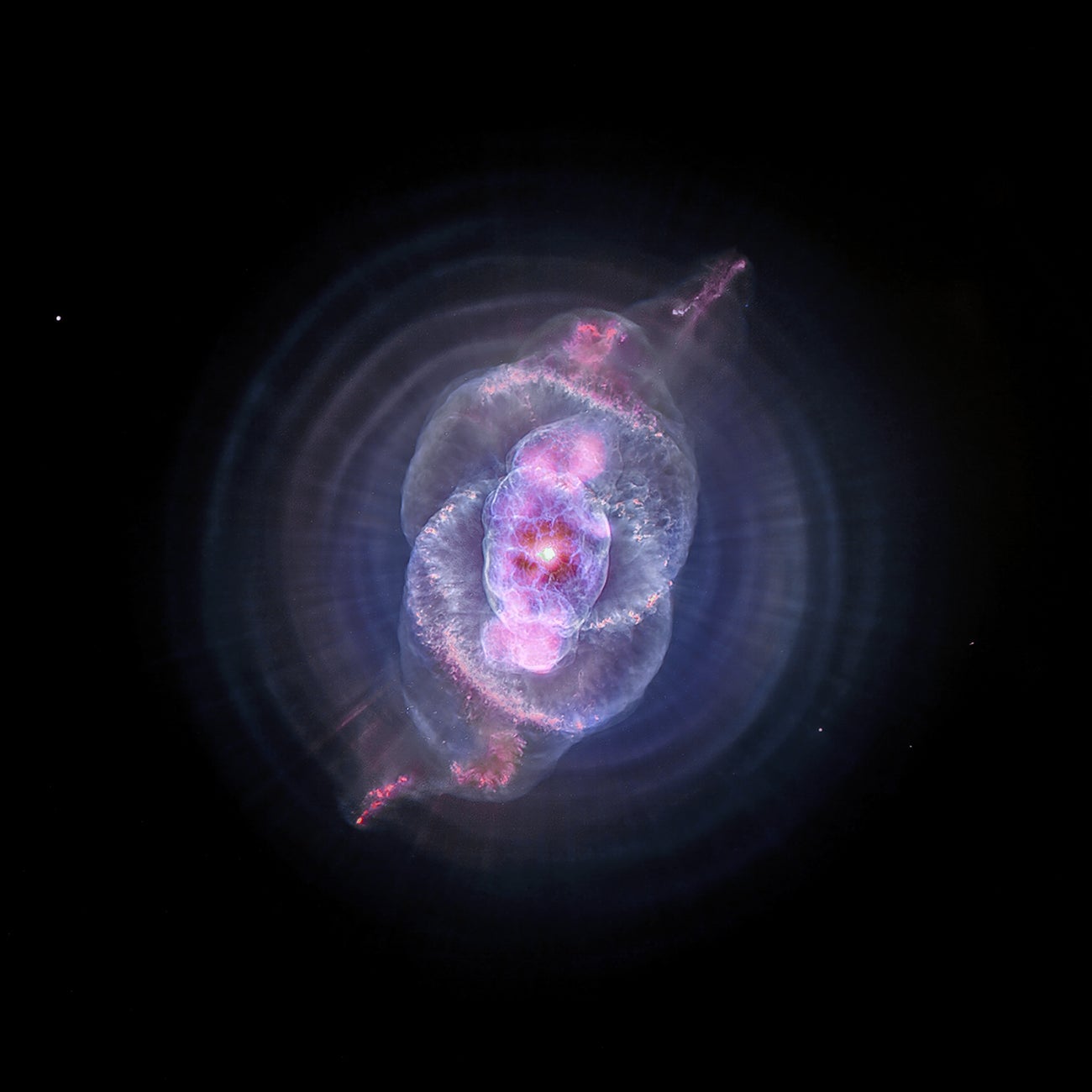

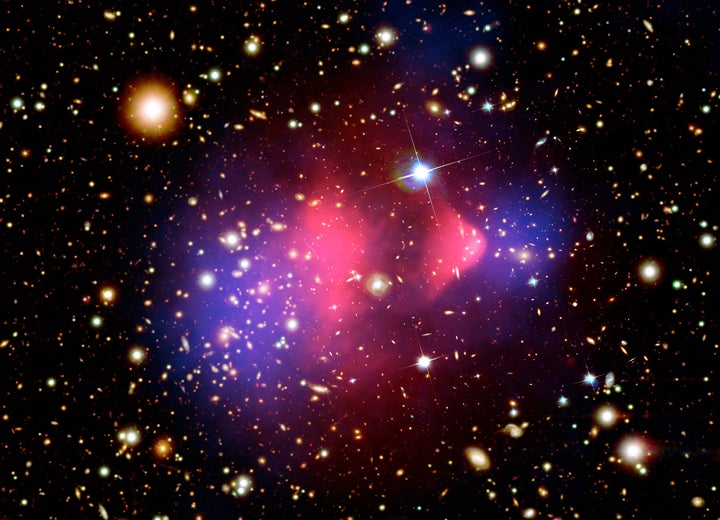

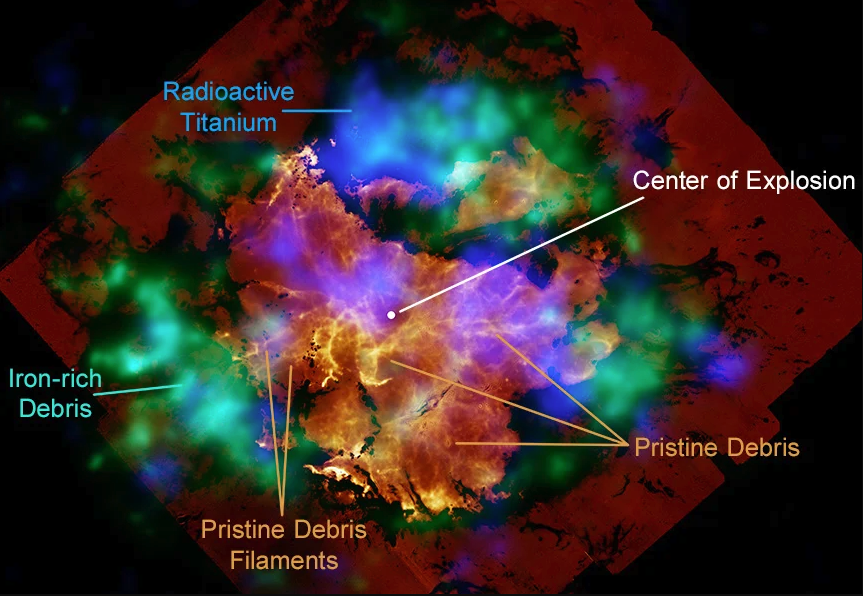

In space, X-rays can tell us about the most explosive phenomena in the cosmos: supernovae, supermassive black holes, colliding neutron stars, and more. Chandra is one of a small number of telescopes—including the European XMM-Newton and Japanese XRISM—that can sense X-rays, the same high-energy light used to image human bones here on the ground. However, Chandra is unique even out of that small bunch, able to see in unparalleled detail. Observations from Chandra have also revealed fluorescence on planets in the solar system, and where mysterious dark matter lurks in a cluster of galaxies.

Since the budget cuts were announced in March, astronomers have rallied together to #SaveChandra, compiling their case for the observatory into a website. “Together, Chandra and Hubble are amongst the most scientifically productive missions in the entire NASA Science portfolio,” reads the Save Chandra website. Astronomers also expect Chandra to be highly complementary to the famous JWST and the upcoming Rubin Observatory in Chile, which will scan nearly the entire sky every night. For example, Chandra can peer into the hearts of high-redshift galaxies seen by Webb, learning more about the supermassive black holes at their centers. It will also be crucial for follow up on the 10 million alerts that Rubin will generate each night by pinpointing short-lived, bright flashes from explosive celestial events.

Astronomers have also been advocating on social media, including sharing personal anecdotes of how important Chandra has been to their scientific careers, from a graduate student describing the importance of Chandra in her education to a professor reminiscing on her first research paper in 2001, which used Chandra data and led to 30 other papers related to the mission in her career.

One of the biggest concerns in the community is the fact that there is no replacement for Chandra on the horizons. Its successor, the Lynx observatory, is “unlikely to launch before the 2050s” according to Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies astronomer Affelia Wibisono—that is, if it launches at all. NASA is considering a smaller X-ray probe mission (to be chosen from a few ideas, including STROBE-X or the Line Emission Mapper), but none of these concepts would fill the gap left by Chandra. Plus, the resulting layoffs from Chandra’s demise would lead to a huge loss of expertise in X-ray astronomy as jobless astronomers are forced to leave the field, creating a huge gap in our ability to even do the science expected from Lynx and other future observatories. Without Chandra, “there’s little incentive or accessibility to doing high energy work for the next decade or so, which really depletes the field and makes it hard to retain momentum in the science that we’re doing,” adds Wong.

With scientists so dedicated to the success of this mission, then, why would it be canceled by NASA?

Chandra’s plight is a symptom of a larger issue: ongoing cuts to science funding in the United States, partially resulting from the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 that limited non-defense spending. NASA’s budget was cut by 2% in the 2024 fiscal year, a stark change from President Biden’s recent request for a 7% increase to their funding. Essentially, NASA leadership has been forced between a rock and a hard place—who would want to choose between one incredible discovery machine and another nearly equally amazing? “We acknowledge that we are operating in a challenging budget environment, and we always want to do the most science we possibly can,” explained NASA Astrophysics director Mark Clampin.

This isn’t the only budget threat facing astronomy this year, either. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab in Pasadena, CA was forced to make major layoffs in February, and the highly ambitious Mars Sample Return program (intended to bring rocks collected by the Perseverance rover, currently on the Red Planet, back home to Earth) is undergoing major restructuring after its original budget was deemed unrealistic. Even ground-based astronomy is faced with hard choices, as the National Science Foundation is now forced to decide on one next-generation telescope instead of the two originally planned for construction.

Astronomy, however, is a mere sliver of the U.S.’s overall budget, and many people are hoping for a future where we can fund more of these scientific endeavors. “Science has such absurdly high national and global return on investment that you can easily advocate for the whole discovery portfolio,” wrote Tremblay in a post on X. Astronomers have also highlighted the importance of astronomy missions for inspiring the next generation of scientists, and keeping the public interested in science overall. “Continuing to operate Chandra would symbolize a renewed dedication to setting big goals,” says West Virginia University astronomer Graham Doskoch. “That’s an idea that has relevance for everyone.”

So, what comes next for the great X-ray observatory? NASA is currently planning a “mini-review” to decide how to best operate Chandra under the new budget constraints, ideally hoping to scale back operations without completely shuttering the program. Meanwhile, Chandra advocates are encouraging people to talk to their government representatives, sign a community letter, and spread the word on social media with resources available on the Save Chandra Website.

“You want to #SaveChandra? The high impact way to do that is to reach out to your representatives and senators,” wrote astronomer Laura Lopez on X. In this critical moment for the future of astronomy, now all eyes are on Congress to see how the budget shakes out in the coming months and years.