Whether it’s in your medicine cabinet, at the bottom of your bag, or rolling around somewhere in your car, chances are you own at least one tube of lip balm. Applying a little to protect the thin skin of your lips from cold winds, searing sun, or any other force that might dry, chap, and crack them feels both common sense and routine. But have you ever stopped to wonder, when did humans start smearing waxy-oily substances on our lips? And how did we get from that basic protective concept to something like a glossy, flavored Bonne Bell Lip Smacker?

Lip balm’s ancient origin story

The origins of lip balm are hard to pin down, says Alicia Schult, the archival researcher and ancient remedy expert behind LBCC Historical Apothecary. Organic materials like waxes decay rapidly and many cultures never wrote down their day-to-day personal care regimens, so the historical record is patchy at best. The records we do have often treat salves as general use, for any part of the body, and blur the lines between care items, cosmetics, and medical treatments.

[ Related: The evolution of sunglasses from science to style (and back again) ]

However, there is archaeological evidence that Neolithic people across the Mediterranean used beeswax to waterproof their pottery, Schult points out. If our prehistoric ancestors knew that wax could seal and protect things, then they likely experimented with it—and with moisture-sealing fats and oils—on their sensitive lips, she argues. Communities across the globe probably independently fiddled their way towards the invention of proto lip balms over and over. That’d explain why we see waxes and oils in the handful of ancient recipes for lip-focused salves and make-up, from Egypt to India to China.

Medieval lip ‘salves,’ from the luxurious to the everyday

Targeted salves, meant to protect or heal “lippes that be cleft and full of chinkes, by meanes of cold or wind,” start to show up in 16th century European texts like The Secrets of the Reverend Maister Alexis of Piemont. The recipes in these medicinal tomes are pretty complex—one calls for goose and hart brains mixed with silver, myrrh, ginger powder, honey, and several other precious ingredients on top of a base of wax and olive oil.

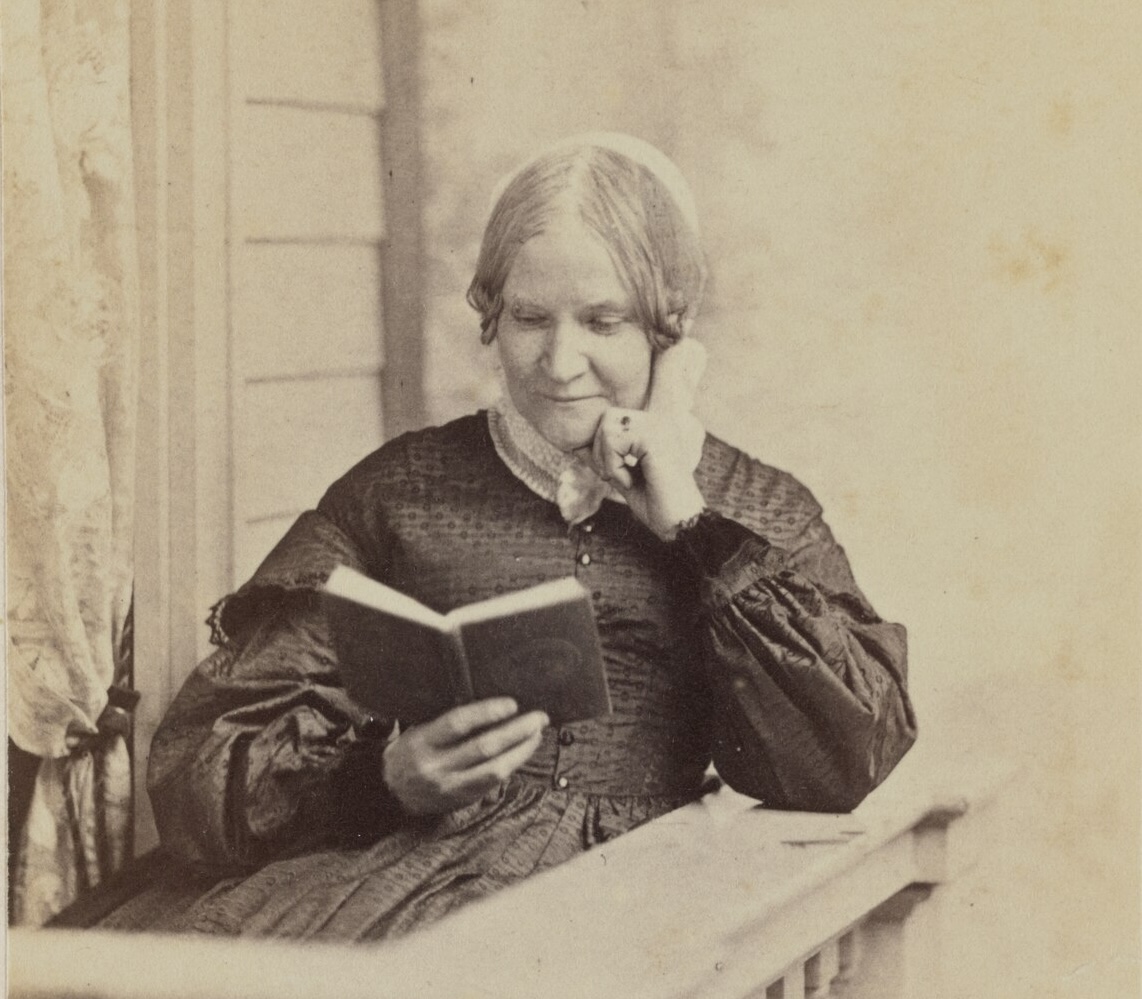

Common folk developed their own cheap and simple remedies, says Schult, passed down from generation to generation at first informally, then, by the 19th century, increasingly in handwritten recipe books or in almanacs meant for a slightly wider audience. (Burt’s Bees famously used an old almanac recipe as the basis for its commercial balm.) Formulas varied according to the local ingredients a family could source, says Schult. In 1833, abolitionist and home economics writer Lydia Maria Child actually suggested using your own earwax as lip balm. Though certainly an easy-to-acquire ingredient, Child’s advice failed to gain much traction.

“Historically, if you took a recipe labeled ‘a salve for the lips’ and brought it to households in different countries, most would recognize the base formula” of some sort of wax or fat and oil, says Schult. (Earwax remedies notwithstanding).

Commercial lip balm takes off

Commercial cosmetics and personal care brands—which emerged in the late 18th century and took off alongside industrialization, mail order systems, and department stores over the next century—slowly standardized these varied formulas, Schult explains, turning lip balm into a uniform, portable, and shelf-stable product. But these mass market balms were nothing like the little twist tubes of soft wax we use today. They came in “hard blocks, designed to endure fluctuating temperatures without melting,” says Schult. People would carry around these blocks in paper or tins and chip bits off to rub on their lips as needed. Other late 18th century lip balms came as a spreadable mash or paste, sold in little pots and jars.

In 1869, lip balm got an upgrade. A doctor named Charles Brown Fleet opened a pharmacy in Lynchburg, Virginia, and started experimenting with different formulas, eventually developing a lip balm with the yellowish color and soft-wax texture we’d recognize today. Fleet never had much luck as a salesman, so he sold the recipe to an associate in 1912, whose wife suggested they mold it into portable sticks using brass tubes for easier use. The brand took a while to catch on, but from the 1930s onward, ChapStick became the standard for lip balms in the United States. In fact, it was so successful that the brand name is now synonymous with the product in America—a process known as genericide. Inventors in Europe and Japan developed similar products around the turn of the 20th century, like LypSyl in the former and Yojiya in the latter, that likewise defined the category in their regions.

The modern lip balm craze

For much of the last century, entrepreneurs have played around with packaging, introducing alternatives to the twist stick, such as squeeze tubes and rub-on balls. Inventors also started mixing in soothing or medicinal compounds into lip balms and marketing multi-use balms—for, say, cold sores or acne pain. Scents, flavors, and glossy colors were added as well, to make balms more attractive, once again blurring the lines between salves and aesthetic cosmetics.

By the 1990s, flavored glosses like Lip Smackers were so popular, and sometimes used so often and heavily, that people started to worry they might be addictive. That fear, doctors concluded in the early 2000s, is baseless. But people are prone to licking their lips when they wear flavorful balms, which can wear away at the protective layer and ironically cause drying and chapping as spit evaporates. Fragrant additives like cinnamon or mint, and ostensibly soothing ingredients like camphor and menthol, may also irritate our lips rather than protect them.

These revelations, alongside growing skepticism towards industrial brands and additives, seem to be fueling a renewed interest in back-to-basics balms. Brands like Burt’s Bees have gained an incredible amount of market share in just a few decades, and researchers are exploring new wax-fat-and-oil mixtures, with an eye towards efficacy and sustainability. But even as new, all-natural options emerge and gain popularity, we’re probably not going back to the days of 19th century DIY lip balms, made of earwax or goose brains. Still, spare a thought the next time you rummage through your bag for the lineage linking your tube of wax to those early salves—and the generations of innovation that brought your favorite lip balm into your hand.