If humans are going to spend as much time in space as some hope we will, it’s important to understand the impact spaceflight has on our bodies. Our bodies in space act like a soda can ready to implode, spaceflight can impact our immune systems, and we lose muscle and bone density at an increased rate.

But how does space affect our ability to produce healthy offspring? A study published August 15 in the journal Stem Cell Reports found that mice stem cells cryopreserved in space can produce healthy offspring.

Germ cells are the precursor cells to eggs and sperm. Studying the impact of spaceflight on germ cells is critical because they directly influence the next generation. If irreversible damage is done to those cells, it will likely be transmitted to offspring. Earlier studies of embryonic stem cells that have undergone spaceflight found some abnormalities. However, the exact cause of the damage is still a mystery.

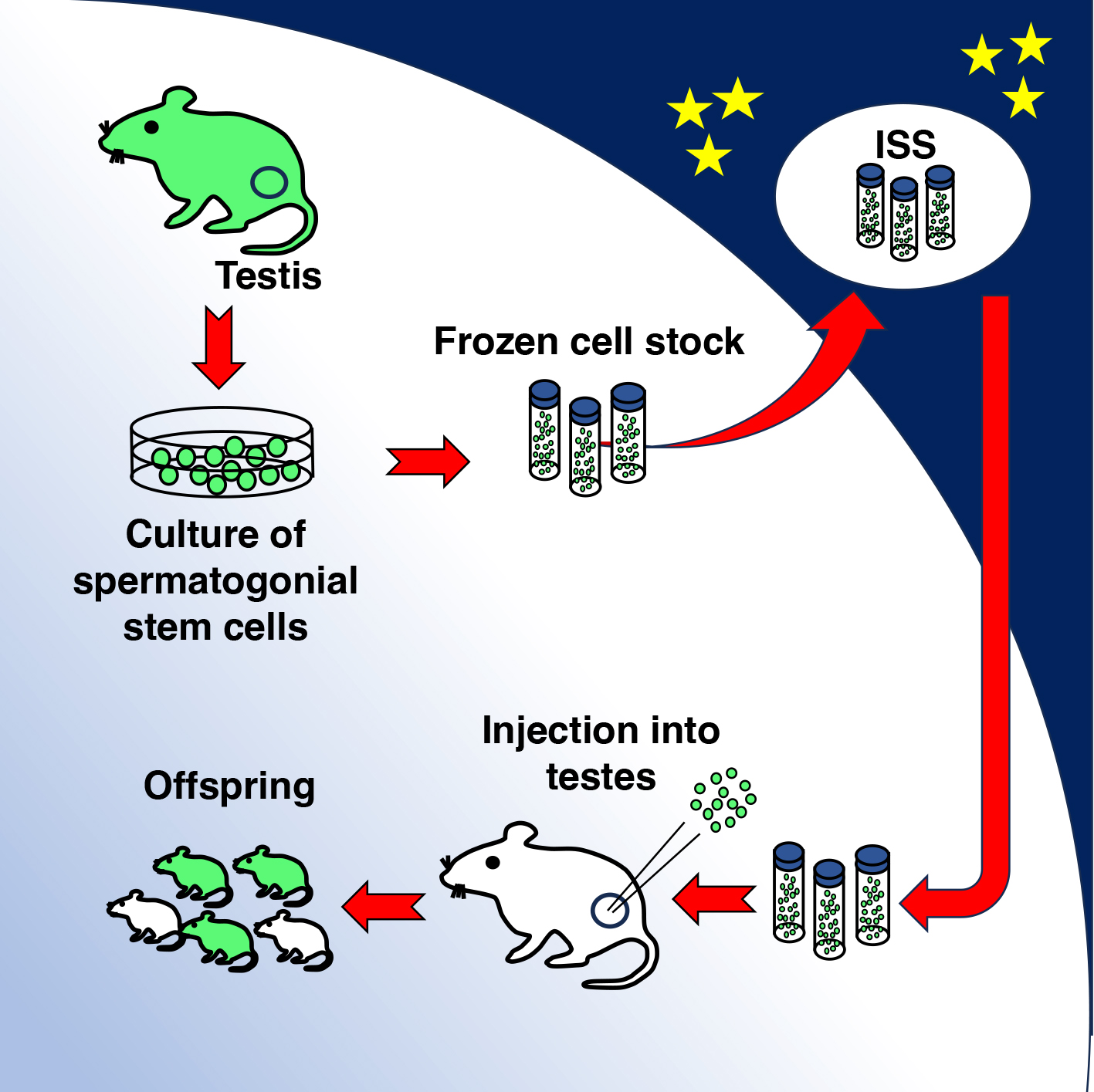

A team at Kyoto University in Japan decided to test the potential damage that spaceflight has on spermatogonial stem cells, a type of germ cell that lives in the testes and turns into sperm cells for reproduction. They used stem cells from mice, which have a much shorter reproductive life span than humans, so any damage to the offspring is easier to spot.

[ Related: This is how space might disturb our immune systems. ]

First, they cryopreserved (or froze) the stem cells. The cells were then sent to the International Space Station and were stored in a deep freezer for six months. When the cells were then returned to Kyoto, the team observed no initial abnormalities.

Once the stem cells were thawed out, they transplanted the cells into mouse testes. Three to four months later, the offspring of the frozen cells were born after they mated the old-fashioned way. The newborn mice were healthy and had normal gene expression. According to the team, this indicates that cryopreserved germ cells can maintain fertility for at least six months– for mice.

“It is important to examine how long we can store germ cells in the ISS to better understand the limits of storage for future human spaceflight,” study co-author and biologist Mito Kanatsu-Shinohara said in a statement.

Stem cells from numerous species can be cryopreserved and still produce healthy sperm. By studying how those cells respond to the freezing process in proxy animals, we could better understand what it will do to the cells that become eggs and sperm during long-haul space missions in the future.

Initially, the team on this study predicted that the spaceflight itself would be more harmful to spermatogonial stem cells than cryopreservation, due to their sensitivity to radiation. However, the opposite was true in this case. The concentration of hydrogen peroxide used in cryopreservation did kill off some of the cells, but there were still minimal differences between the pre- and post-spaceflight germ cells.

Several more studies are needed to reach conclusions for humans. While the mice offspring appear normal and do not have abnormal DNA patterns, long-term health issues still cannot be ruled out. Only when the lifespan and fertility of these mice and subsequent generations of mice are properly analyzed will we know for sure.

“We still have some spermatogonial stem cells frozen on the ISS, so we will continue to conduct further analysis,” says Kanatsu-Shinohara.