When the brain releases oxytocin during sex, childbirth, breastfeeding, and social interactions, the hormone supports strong feelings such as attachment, trust, and closeness. That’s why oxytocin is frequently nicknamed the love, cuddle, or happy hormone—even though it’s also linked with aggression. To continue investigating the biological role of oxytocin, a team of researchers studied it with scientist’s poster species for love and friendship, the prairie vole (Microtus ochrogaster).

The small rodents found throughout central North America have bonds that are “similar to human friendships in the sense that they are selective and long-lasting. Voles form strong, stable bonds with specific peers,” Markita Landry, a chemist from the University of California (UC), Berkeley, tells Popular Science. “These relationships can persist for long periods, even when other social options are available, which makes them an excellent model for studying the biology of friendship.”

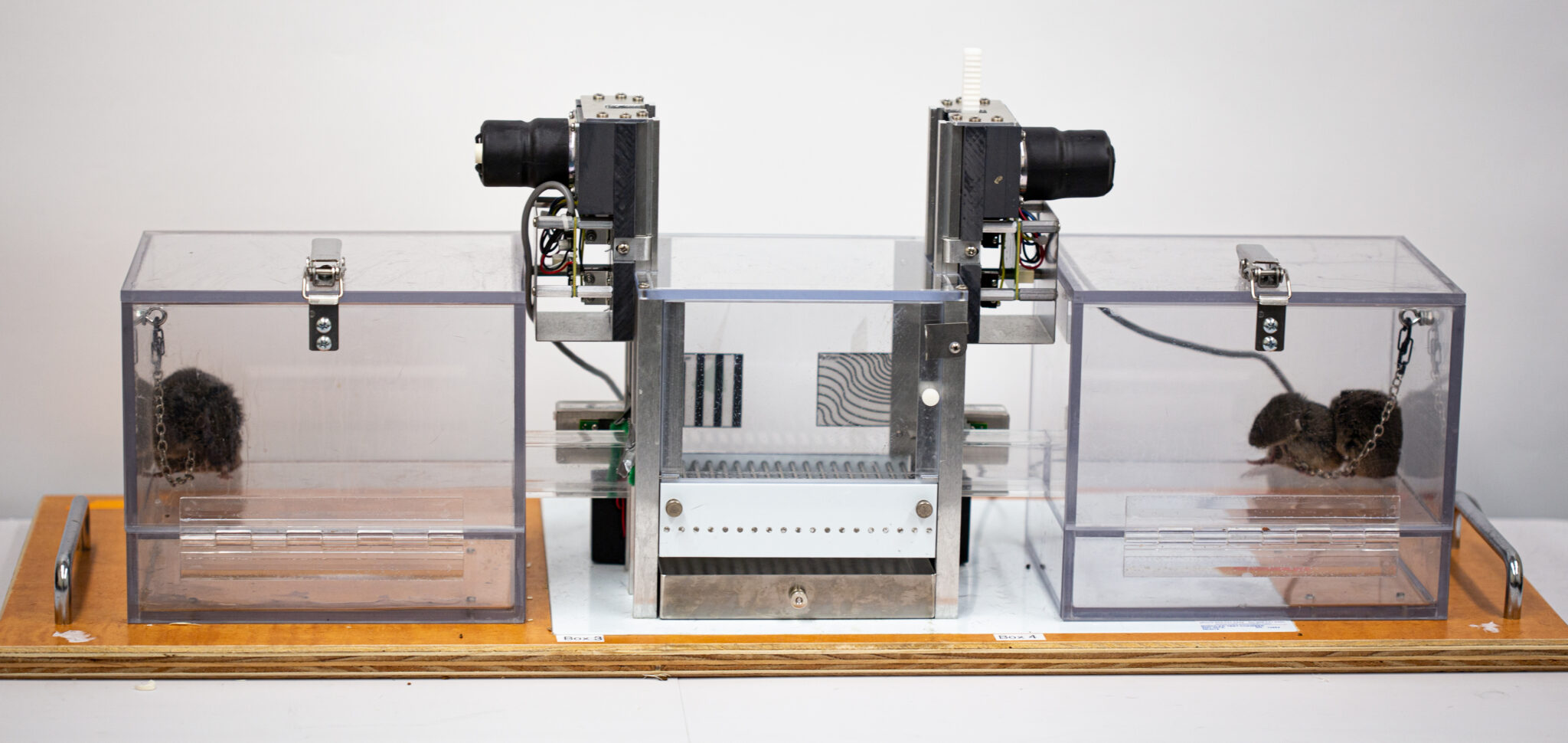

In a study recently published in the journal Current Biology, Landry and her colleagues analyzed the behaviors of voles that were genetically modified to lack oxytocin receptors. An oxytocin receptor, she explains, is like a “lock” for which oxytocin is the “key.” Essentially, the hormone needs to open the lock in order to influence brain activity.

Voles usually form friendships within a day or two, and then prefer familiar companions instead of strangers, or other voles they don’t know, Annaliese Beery, senior author of the study and a neuroscientist at UC Berkeley tells Popular Science. However, the prairie voles in this study without oxytocin receptors took longer than normal voles to make friends. They were also less aggressive toward strangers and avoidant of those they didn’t know.

[ Related: These fuzzy burrowers don’t need oxytocin to fall in love. ]

What’s more, when the researchers challenged the friendships by putting the pairs of voles in a group situation, the genetically modified animals immediately began mixing. By comparison, regular voles would stay close to their friends for a period of time before socializing with strangers.

In another experiment, the team put the voles in a space where they had to press levers to reach either a friend, a mate, or a stranger. According to Beery, regular female voles typically press the levers more in order to get their partner than to get a stranger, whether they are in a peer or mate relationship. The mutants without the oxytocin receptors also press more to get to a mating partner, but not in the peer relationships.

The receptor-deficient voles didn’t seem to experience the same rewards from bonding with friends that normal voles would, meaning they did not preserve any significant preferences.

CREDIT: Beery lab/UC Berkeley

“We found that oxytocin is essential for building and keeping these bonds, and that it also shapes how voles interact with strangers,” Landry explains.

Within the context of building bonds, oxytocin seems to play a role particularly in the selectivity of friendships. “This broadens the view of oxytocin from being just the ‘love hormone’ to a more general ‘social relationship’ hormone that supports both romantic and platonic connections,” she says.

More broadly, the researchers suggest that understanding friendship biology could ultimately provide insight into conditions that make it harder for the afflicted individual to create or preserve social bonds, such as schizophrenia and autism.