When it comes to food, green is often shorthand for health. If it’s green, the prevailing wisdom is it must be good for you. So, what if you took the compound behind the color of spinach and broccoli and distilled it down into a supplement? That must be extra good for you, right?

According to influencers promoting chlorophyll water, the answer is a resounding yes. Videos claim that drinking ‘chlorophyll water’ (most often, actually a derivative of chlorophyll called sodium copper chlorophyllin) is an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory fast track to better breath, better skin, and more.

However, science tells a slightly different story. Despite some promising applications of the green stuff, there is very little research supporting the idea that chlorophyll or chlorophyllin supplements are a cure-all. Here’s what we actually know.

What is chlorophyll?

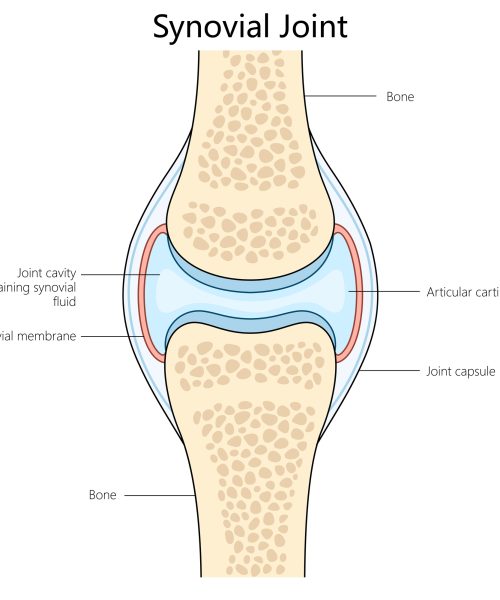

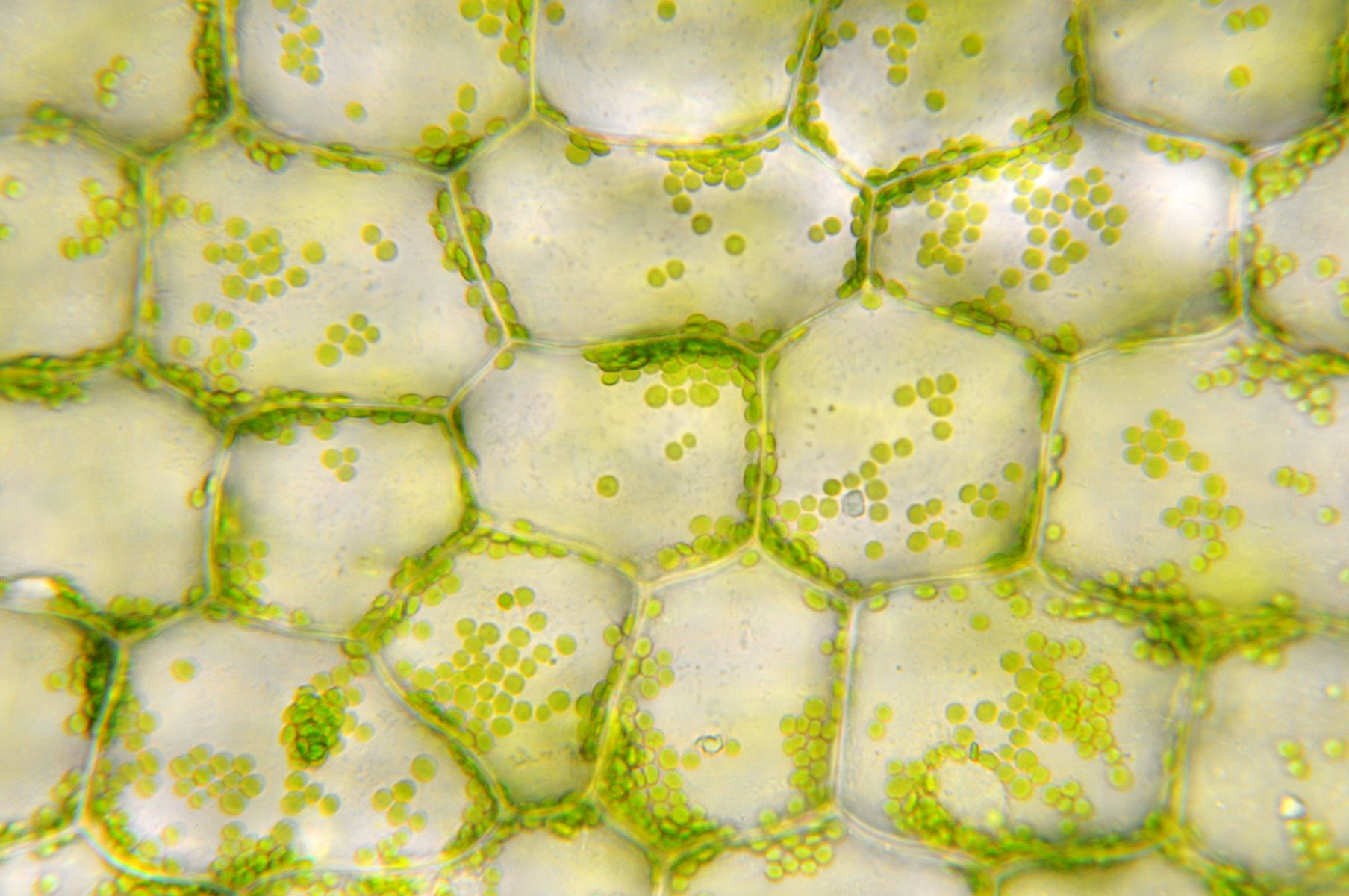

Chlorophyll is the pigment in plants that lends them their green color. It primarily comes in two forms: chlorophyll a and b. Each form captures slightly different wavelengths of sunlight that plants then convert into energy. Chlorophyll is naturally present in all the green fruits and vegetables we eat, from kale to parsley to peppers.

On a molecular level, chlorophyll is an array of carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, and nitrogen atoms centered around a metal ion, usually magnesium.

In this natural form, chlorophyll is a fat soluble molecule that doesn’t mix well with water. So, the green liquid TikTok-ers are squeezing into their glasses and bottles is a modified, semi-synthetic compound known as sodium copper chlorophyllin (SCC). It contains copper at its center instead of magnesium, and the addition of sodium ions makes it water soluble. SCC has long been used in small amounts as a color additive in certain foods, and has more recently become a popular supplement, taken for the aforementioned, purported wellness benefits.

Where did the wellness trend come from?

Human health researchers have studied chlorophyll and related compounds for a long time, Rachel Kopec, as associate professor of human nutrition at the Ohio State University, tells Popular Science. In the 1940s, laboratory tests indicated chlorophyllin had some antibacterial properties. This led to both animal and human tests of chlorophyll derivatives as a topical treatment for wounds, to speed recovery and minimize inflammation. Research here does suggest a healing benefit from certain formulations of topical SCC ointments and sprays. (Though it’s possible some of the effect comes from the antibacterial and peptide-enhancing nature of copper itself, not chlorophyll, Joshua Zeichner, an associate professor of dermatology at Mount Sinai Hospital, tells Popular Science.)

Decades ago, physicians also tested chlorophyll and chlorophyllin for its potential to reduce bodily odors, first as a topical on festering wounds and then as an oral supplement to lessen the unpleasant smells associated with maintenance of colostomies or ileostomies. This is how chlorophyll first went from an external treatment to an internal supplement.

Does chlorophyll really work?

Initial studies suggested taking chlorophyll can control odors, but these first analyses lacked appropriate control groups for comparison. One 1989 follow-up study found that chlorophyll supplementation was no more effective at minimizing fecal smells than a placebo. Though case studies and anecdotal reports of chlorophyll’s anti-odor efficacy continue to persist, including among social media influencers who claim drinking chlorophyllin fixed their bad breath. Yet many brands of chlorophyllin drops also contain peppermint flavorings, so consumers might simply be noting the same sort of benefit one can get from a breath mint.

Amid enthusiasm around antioxidants in medical research beginning in the 2000s, SCC became the subject of many test tube experiments assessing its ability to neutralize unstable molecules within the body. In the lab, studies suggest SCC does show clear antioxidant activity. Some animal studies also indicate SCC supplements may reduce damage from chemical carcinogens and radiation, but that’s when supplements are given alongside the toxins or radiation dose.

Related Health Stories

The only demonstrated human tests of chlorophyll derivatives’ toxin-fighting potential have been with aflatoxin, a naturally occurring toxin common in some grain supplies that can increase the risk of liver cancer. In studies conducted in Qidong, China, a region where aflatoxin exposure is high, short-term tests showed that taking chlorophyllin with meals reduced the level of DNA damage from aflatoxin. Outside of populations with unavoidable, high levels of aflatoxin exposure, research doesn’t yet support chlorophyll or chlorophyllin as a cancer-fighting supplement.

Notably, one of the reasons chlorophyll seems to work against aflatoxin is because of how well it binds to the toxin in the digestive tract and then leaves the body. Very little natural dietary chlorophyll is absorbed, says Kopec.

“Most of the chlorophyll, like greater than 95% of what you or I might eat from a green plant, is excreted in the feces,” she explains. In tests of semi-synthetic derivatives, like SCC, she adds that levels of human absorption also seem low or are not yet clear. Currently, she’s working on developing and testing iron-containing chlorophyllin compounds as a way of supercharging iron supplements for people with a deficiency, but still the challenge remains of assessing how much is absorbed. So, claims that taking chlorophyll as a once daily supplement will protect you from cancer are unfounded. The safer bet might just be to eat something green with every meal—the standard ‘eat your vegetables’ advice you’ve likely heard your whole life.

When it comes to skin care, a handful of pilot studies and case reports have evaluated chlorophyllin topical treatments for facial redness, acne, and signs of sun damage and aging, like fine lines and pore size. These studies have been small, with fewer than a dozen participants—but do show promising results, with subjects experiencing improved symptoms across clinical tests after weeks of treatment. Yet placebo-controlled, large-scale clinical trials haven’t yet been done and the ideal dose and formula for skincare hasn’t yet been evaluated, Zeichner says. And again, copper might be more at play here than the green goop, he notes.

Neither Zeichner nor Kopec were familiar with any peer-reviewed studies of ingested chlorophyll or chlorophyllin supplements as an acne treatment. “Just because there isn’t a ton of research doesn’t automatically mean that something isn’t effective,” Zeichner says. “But in order for it to become a mainstream recommendation, it really does need research behind it to prove effectiveness and safety.”

Is chlorophyll safe?

Consuming natural chlorophyll, as it’s found in plants, is perfectly safe and part of a healthy balanced diet. “If you’re getting it from spinach, which is typically the richest chlorophyll source in the Western diet, you’re also getting fiber. You’re getting vitamin A and all the other vitamins and minerals that are found in spinach. You’re providing fuel for your microbes in your gastrointestinal tract. I always like to promote a whole foods approach,” Kopec says.

And in small amounts, sodium copper chlorophyllin is well-established as safe, given its use as a food coloring. Various forms of chlorophyllin have been used clinically in humans for more than half a century with no known toxic effects. Mild side effects like diarrhea, discolored urine or feces, and increased sun sensitivity have been reported by some.

However, the doses influencers are promoting with unregulated supplements makes things murkier. “Supplements are the wild west,” Zeichner says. “I think that you should purchase chlorophyll from a reputable distributor, but I just can’t tell you who’s a reputable distributor.”

Kopec also has concerns. “Once you start concentrating anything, there’s always risks of toxicity,” she says. In small amounts, copper itself is an essential micronutrient. But take too much and you can end up with copper toxicity. Again, the copper in SCC doesn’t seem to be particularly well absorbed, but at least one study suggests a portion does make it through the digestive barrier. And, if a supplement contained unbound copper because of improper production, it could pose a danger. “‘Are people actually getting what they are being told they’re getting?’ is one question. And then the other question is, ‘How much copper is actually in there?’,” Kopec says.

Thankfully, these possible risks haven’t seemed to materialize. For now, the most likely harm chlorophyll supplements pose is “to your pocketbook,” Zeichner says. “These preparations are not inexpensive,” he notes. A small dropper bottle containing less than 60 milliliters of chlorophyllin costs upwards of $20, which might last someone less than two to four weeks, depending on their regimen. Clearly though, that hasn’t dissuaded the chlorophyll-curious. As of writing, the linked product is out of stock.

In his own practice, Zeichner does talk about diet with patients. And research is increasingly revealing the role that nutrition plays in skin health. High sugar intake, dairy, and certain other food allergies and intolerances are known to trigger skin disorders or worsen acne, he says. But, short of specific prescription medications like isotretinoin (i.e. Accutane) there is no single food or ingested supplement that he’s aware of that can clear up your skin. “Diet is just one part of the story,” he says.

“If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is,” he adds.

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.