Japan’s Hyabusa2 space probe is currently about 105.5 million miles away, en route to its second asteroid rendezvous. However, revised data collected from a global network of observatories now indicates that the space rock designated as 1998 KY26 will look and behave far differently than astronomers previously theorized—and it may prove disastrous for the tiny explorer.

In 2010, the Japanese Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) made history when its Hayabusa probe became the first spacecraft to not only land on and launch from an asteroid (Itokawa), but successfully return to Earth with samples. Hayabusa2 continued the project’s legacy by accomplishing a similar retrieval from another asteroid (Ryugu) in 2020.

After delivering its payload, JAXA engineers then sent the small vehicle back out into the void towards asteroid KY26 for a final collection mission slated to take place in 2031.

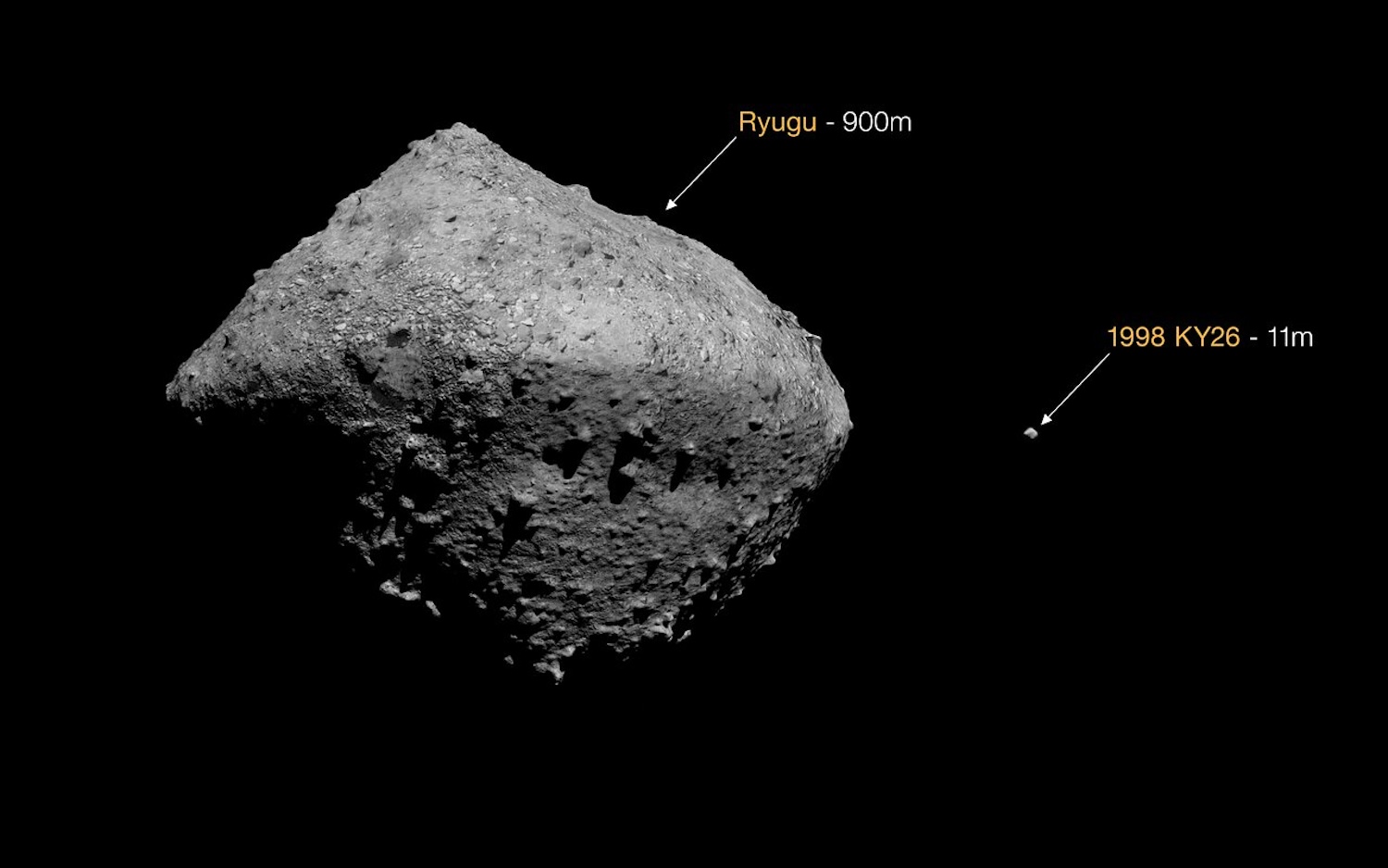

Unlike prior targets, KY26 was chosen for its comparatively diminutive size. The asteroid Itokawa was only about 820-feet-wide and Ryugu was 2,950-feet-wide. KY26 was initially estimated to be only around 100 feet in diameter. Landing a probe on such a small target while it hurtles through space is difficult enough, but astronomers always knew the asteroid’s theorized dimensions might shift as they gathered more information.

However, based on the most recent observations amassed by tools including the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope (VLT), KY26 is much smaller than anticipated.

ESO/M. Kornmesser. Asteroid models: T. Santana-Ros, JAXA/University of Aizu/Kobe University

“We found that the reality of the object is completely different from what it was previously described as,” said Toni Santana-Ros, University of Alicante researcher and co-author of a study on the new findings published in Nature Communications.

In actuality, KY26 is nearly three times tinier than Santana-Ros and colleagues thought. At only about 36-feet-wide it is smaller than a full-sized school bus, and barely larger than the Hayabusa2 space probe itself. Not only that, but the asteroid’s rotation is about twice as fast as initial estimates.

“One day on this asteroid lasts only five minutes,” explained Santana-Ros, adding that the revisions make the Hayabusa2 mission “even more interesting, but also even more challenging.”

It’s also still unclear what the space probe will find once it arrives in about six years. Current data suggests the asteroid features a bright surface made of solid rock, possibly broken off of a distant planet or another asteroid. At the same time, there is still the possibility that KY26 is actually a mass of loose rubble piles glombing together thanks to gravitational pull.

“We have never seen a ten-meter-size asteroid in situ, so we don’t really know what to expect and how it will look,” said Santana-Ros.

Hyabusa2’s gold standard outcome remains returning to Earth again with even more asteroid samples. But even if its final journey culminates in a fatal collision, it will still provide researchers with a trove of data on these fascinating space rocks..

“The amazing story here is that we found that the size of the asteroid is comparable to the size of the spacecraft that is going to visit it,” Santana-Ros said. “And we were able to characterise such a small object using our telescopes, which means that we can do it for other objects in the future.

This may help inform plans for future near-Earth asteroid missions, or possibly even mining operations in space. And in the end, Hayabusa2’s mission could one day save lives.

“We now know we can characterise even the smallest hazardous asteroids that could impact Earth, such as the one that hit near Chelyabinsk, in Russia in 2013,” added study co-author Olivier Hainaut.

After all, the 2013 incident involved an asteroid only slightly larger than KY26, and it released approximately 30 times as much energy as the Hiroshima atomic bomb.