Quickly: Picture a breakfast. If you live in the United States, there’s a good chance you were picturing some combination of eggs, bacon, cereal, and/or pancakes. Of course, we also know that a classic British breakfast consists of beans and fried bread—two savory foods most Americans don’t associate with their first meal of the day. Is there a science behind why we think of some foods as breakfast and others as not?

The answer is…not really. It’s a good example of a category that feels objective but is actually cultural. We eat certain foods for breakfast because we think of them as breakfast foods, and we think of them as breakfast foods because we tend to eat them for breakfast. Breakfast isn’t a scientific category.

Different cultures eat different breakfasts

I grew up in Canada, the country most culturally similar to America. I still remember the first time, as a kid, that I saw donuts offered as a hotel breakfast food during a road trip south of the border. It blew my mind: I thought of donuts as a mid-morning treat, not a breakfast one, and had no idea those categories could be blurred.

And cultures all around the world have different categories of what is and isn’t breakfast food. The Wikipedia page for breakfast by country has a fascinating breakdown of this. In Japan, it’s common to eat things like rice, grilled salmon, and vegetables for breakfast, whereas in parts of Latin America, rice and beans are commonly included.

That’s all to say that the specific foods people eat for breakfast are a product of the culture they live in. And, it turns out, the culture you live in can be intentionally shaped.

The breakfast conspiracy

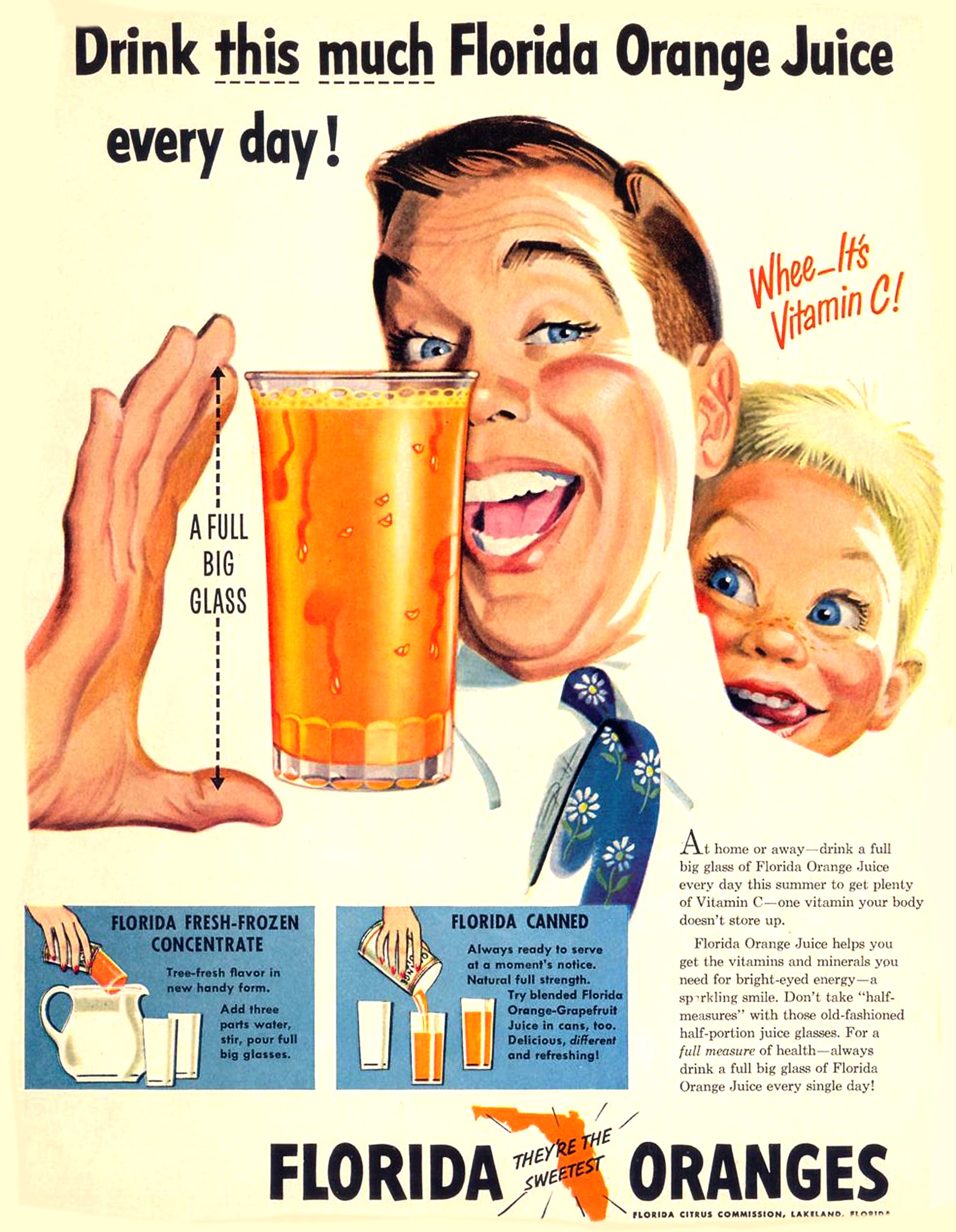

Orange juice, bacon, and eggs—the all-American breakfast throughout history. Or is it?

At least one part of that combination dates back to a specific advertising campaign. Edward Bernays, the nephew of Sigmund Freud, is arguably the reason we think of bacon as a breakfast food today.

As the economist June Zaccone at Hofstra University outlined in a paper, Americans used to eat lighter breakfasts—some coffee and a roll, for example. Bernays, working for the Beech-Nut packing company in the 1920s, wanted to increase demand for bacon. He “decided that doctors were most likely to convince Americans about food,” according to the paper. He conducted a survey of doctors that “found that doctors recommend a hearty breakfast.” He used this survey, which didn’t mention bacon and was not exactly scientific, as the basis for a series of ads claiming bacon and eggs is the true all-American breakfast.

It worked. And this is hardly ancient history—Bernays lived long enough that there’s even a video where he outlines the scheme. He worked in PR for decades after this, where he came up with diabolical campaigns like the one that linked Lucky Strike cigarettes with feminism.

Orange juice became a breakfast beverage because there was a surplus of oranges in the 1940s. Growers, rather than reducing production, decided to find new ways to market their product, and positioning it as a breakfast beverage worked well. This resulted in ads suggesting that drinking massive amounts of orange juice for breakfast was healthy. This video by Phil Edwards offers a great overview of some of the history of orange juices and its place in pop culture, if you’re interested.

“The most important meal of the day”

Marketing’s influence on breakfast goes even further: the idea that breakfast is the most important meal of the day also has its origins more in marketing than science. The exact phrase “breakfast is the most important meal of the day” became popularized by a 1944 campaign for Grape Nuts. Over time it became a cultural truism, despite the scientific research on the relative importance of breakfast being mixed at best.

Cereal companies have been particularly effective at using a combination of marketing and scientific-sounding claims. Until the industrial revolution breakfast tended to consist of leftovers from the day before. Concern about workers suffering from indigestion is part of what motivated the widespread popularity of breakfast cereals at that point, which were aggressively marketed as a healthier alternative to heavy foods like meat.

Breakfast is whatever you eat in the morning

This isn’t to say that bacon, eggs, cereal, and orange juice aren’t a good breakfast—they all have nutritional upsides and downsides. However, our ideas of what qualifies as breakfast food are cultural distinctions, not scientific ones. We’ve collectively decided as a culture that certain foods are eaten in the morning and certain foods are not. Sometimes people even intentionally influence the culture of breakfast in order to sell specific goods.

That’s not to suggest that categories are arbitrary—they all exist in a specific cultural context, affected by all sorts of facts, from the schedules we keep to the media we consume. But our idea of “breakfast foods” isn’t based on any kind of objectivity. People put eggs in stir fry, bacon on pizzas, and cereal in ice cream—none of those things become breakfast when you do so.