While ultraviolet (UV) light is harmful for human skin, it could be a new tool in the fight against airborne allergies. A study recently published in the journal ACS ES&T Air found that UV light can disarm common indoor allergens in only 30 minutes.

“We have found that we can use a passive, generally safe ultraviolet light treatment to quickly inactivate airborne allergens,” study-author Tess Eidem, a microbiologist at the University of Colorado Boulder, said in a statement. “We believe this could be another tool for helping people fight allergens in their home, schools, or other places where allergens accumulate indoors.”

Why allergens can’t die

Just a quick sniff of cats, mold, dust mites, or trees is enough to trigger symptoms from swollen eyes to itchy skin and even impaired breathing. Indoor allergens can persist for months, even if the original source is gone. Repeated exposure can lead to or exacerbate asthma symptoms.

If a person allergic to cats walks into a room and sneezes, it’s not the cat itself they’re allergic to. Instead, it’s likely little airborne bits of a protein called Fel d1 that is produced in cat saliva. This protein spreads when they lick themselves and it ends up in microscopic flakes of dead skin floating in the air that we call dander.

When humans inhale these dander particles, our immune system creates antibodies that stick to the protein’s unique 3D structure. This then triggers an allergic reaction. According to the Cleveland Clinic, an allergy sufferer’s immune system creates a special antibody called immunoglobulin E (IgE) the first time they encounter an allergen. Each of these antibodies is sensitive to a specific kind of allergen. Some people may have multiple IgE antibodies that are sensitive to multiple types of allergens. If you are not allergic to cats, your immune system doesn’t make any IgE when exposed to cat dander.

Plants, mice, dogs, and dust mites all emit their own unique proteins. Each of which have distinct structures. While we can kill viruses and bacteria with cleaning agents and antibiotics, allergens cannot be killed simply because they were never alive to begin with. They are just a byproduct of many living things.

“After those dust mites are long gone, the allergen is still there,” said Eidem. “That’s why, if you shake out a rug, you can have a reaction years later.”

Washing walls, vacuuming, air filters, and regularly bathing pets can only go so far and are difficult to maintain long-term. Eidem and the study’s co-authors, environmental engineer Mark Hernandez and microbiologist Kristin Rugh, sought a simpler way to get rid of allergens. Instead of eliminating the proteins that cause allergens, the team explored changing the protein’s structure so that the immune system wouldn’t recognize the allergen. They liken this process to unfolding an origami animal.

“If your immune system is used to a swan and you unfold the protein so it no longer looks like a swan, you won’t mount an allergic response,” explained Eidem.

How UV light can eradicate allergens

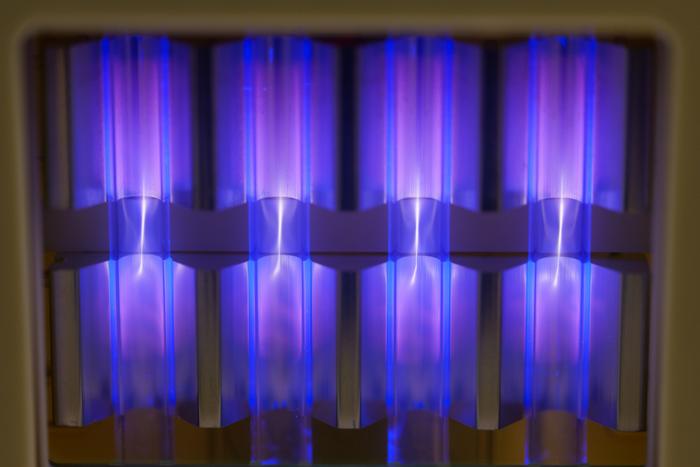

UV light could be the answer. Earlier studies have shown that UV light can kill airborne microorganisms, including the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) virus. UV light is also used to disinfect equipment in hospitals and airports. However, the light is usually incredibly strong at a wavelength of 254 nanometers. At this level, users must wear protective equipment to prevent damage to skin and eyes.

Instead, Eidem used 222-nanometer-wavelength lights. This less-intense alternative of UV light is considered safer since it does not penetrate deep into cells. However, it is not completely risk-free. Some risks include ozone pollution if it is not used in a well ventilated space and used too frequently, so its use should be limited.

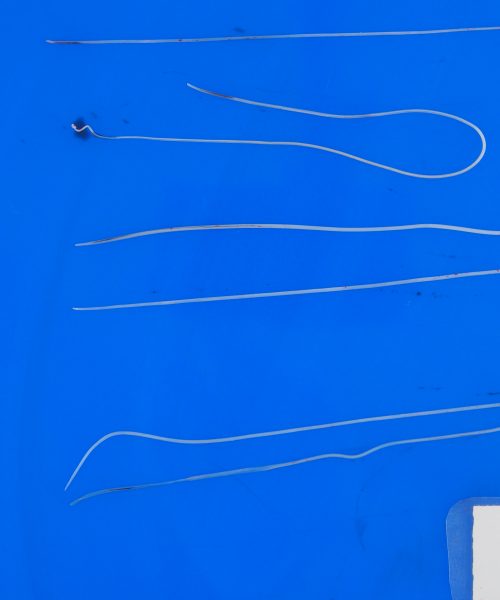

Eidem and the team pumped microscopic aerosolized allergens from mites, pet dander, mold, and pollen into an unoccupied and sealed 350-cubic-foot chamber in one of the campus’ labs. Next, they switched on four UV222 lamps about the size of a lunchbox, that were placed on the chamber’s ceiling and floor.

They sampled the air at 10-minute intervals and compared it to untreated, allergen-filled air and saw some significant differences. In the treated samples, the antibodies no longer recognized many of the proteins, meaning that the immune system had a harder time recognizing them. After only 30 minutes, airborne allergens effectively decreased by about 20 to 25 percent on average.

“Those are pretty rapid reductions when you compare them to months and months of cleaning, ripping up carpet, and bathing your cat,” said Eidem.

Help for millions of allergy sufferers

While UV222 lights are already commercially available for use, Eidem envisions portable versions for people to switch on when they visit a friend with a pet or clean out a dusty basement could exist in the future.

Additionally, UV222 systems could potentially protect workers that are frequently exposed to allergens, including those who work around live animals. Since one-in-three adults and one-in-four children in the United States have allergies, Eidem hopes future research could even save lives.

“Asthma attacks kill about 10 people every day in the United States, and they are often triggered by airborne allergies,” Eidem said. “Trying to develop new ways to prevent that exposure is really important.”