I drove up to my first sound bath experience not knowing quite what to expect. The meditative practice, which utilizes chimes, gongs, and an arsenal of “vibrational musical instruments,” has existed in various forms for millennia but has seen a post-pandemic resurgence, particularly among the burgeoning, influencer-boosted online wellness community.

Practitioners swear by a sound bath’s therapeutic effects, saying the various sound waves generated by the instruments can relax and rejuvenate the body, alleviate tension, and reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety. For some, being bathed in a cascading orchestra of sound sparks a sense of spiritual awakening. Some people cry during the session; others fall asleep and snore.

My rationale for lying back in a chair beside three strangers and enduring roughly 50 minutes of sonic overtures came from a place of humble skepticism. The academic literature surrounding sound baths falls somewhere between emerging and thin, depending on one’s point of view. One peer-reviewed study from 2016 found that participants reported “significantly less tension, anger, fatigue, and depressed mood,” following a session. Other studies have reported similar findings.

But wellness influencers often promise far more ambitious benefits, less rooted in science. Some sound healing practitioners have claimed the power of sound waves can treat arthritis, manifest wealth, and even cure cancer.

Admittedly, my cynical instinct had more to do with some of sound baths’ messengers than the actual practice itself. It can be increasingly difficult to separate the supposed objectivity of modern wellness practices from the questionable profiteering of massively popular companies like Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop and shady online influencer personalities. Still, reservations aside, one can’t immediately discount the anecdotal experiences people have reported across cultures for generations.

Entering a world of sound

My experience, which took place in a small four-room meditation bar in a suburb of Austin, Texas, began with me and three others in my group session lying flat on cozy recliners resembling massage chairs. Aside from the cadre of supine bodies, the room was filled with about a dozen instruments, ranging from chimes and Tibetan singing bowls to larger gongs—the kind you might have last seen at a high school pep rally.

Our guide, an emotionally observant woman named Stacie, briefly walked us through each instrument’s sounds. She then had us close our eyes and engage in deep breathwork, narrated by a spoken-word meditation. (I’ve had my own daily meditation practice for half a decade, so this aspect at least felt familiar.)

Then the chimes started. High-pitched and assertive, the sounds quickly filled the room, complementing our instructor’s monologue in a kind of meditative symphony. As she gradually approached me, chimes in hand, I could feel their sharp vibrations, like an invisible worm scurrying its way in one ear and out the other.

What began as a startling invasion of sound slowly faded into something more tranquil as Stacie moved on to the singing bowls. They emitted a deep, bass-toned wombling, like an ancient Doppler effect, that seemed to encourage slower, deeper breaths. Roughly 15 minutes in, my thoughts, once pronounced, blurred into a gray daze. Deeply personal reflections, like those about my recently deceased father, mingled with other seemingly random artifacts. Before we began, the practitioner had said her goal was to guide us into a semi-conscious “space between awake and asleep.” Mission accomplished.

When the high-pitched bells rang once more at the tail end of the experience, I felt myself suddenly jolted back to awareness. At least 20 minutes had passed in what seemed like the blink of an eye. The hypnotic session left me feeling distinctly relaxed and calm. I drove the 20 minutes back home through chaotic Texas traffic without a trace of my typical short-fused rage.

Something had happened—but what exactly? Did the scientific literature support this experience or had I, and others, simply willed the purported effects into existence?

Sound therapies were a “turning point” in a prominent researcher’s life

To get a better sense of what I had experienced, I spoke with the leading academic researcher on sound baths, University of California clinical research psychologist Tamara Goldsby. Goldsby has published several peer-reviewed studies on the effects of sound baths and runs the site Sound Healing Central.

Though the term “sound bath” can mean different things to different people, Goldsby defines it as a “form of relaxation, stress relief, and, at times, healing” that utilizes vibrational instruments. These instruments most often include Tibetan singing bowls, crystal singing bowls, and gongs, but can also encompass Tingshas, other bells, didgeridoo, and the handpan.

Goldsby’s connection with sound baths goes beyond distant, impersonal academic analyses. She says she first became aware of the practice over 15 years ago when she met a man from Nepal who was playing and selling Tibetan singing bowls at a street fair. The deep, resonant vibrations from the bowls immediately drew her in and produced what she describes as a “turning point” in her life. Goldsby began attending the weekly sound healings the man was conducting.

“In addition to the stress-reduction that I felt during these sound baths, I noticed anecdotally that the participants were invariably much calmer, more relaxed, and peaceful after the sound bath,” Goldsby said. “As a research psychologist, it became inevitable for me to want to study this intriguing effect, which I did.”

Researchers have found evidence of sound bath-like practices dating back to the ancient mystics of Egypt, Greece, and societies in the Himalayan mountains. Though the practice never really disappeared, Goldsby says the modern concept of sound baths and sound healing in Western society is relatively new. Buttressed by a resurgence during the pandemic-era lockdowns, sound baths are increasingly becoming common fixtures at spas, yoga studios, rehab clinics, and wellness retreats. They have even been offered at corporate events and on stage at the Coachella music festival.

What does the science say?

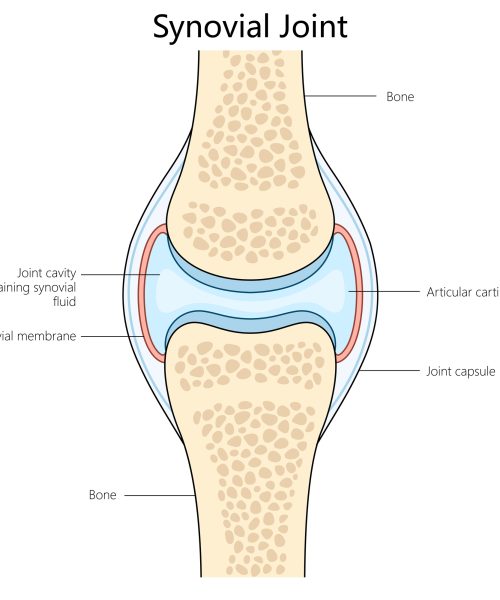

Describing what is actually happening on a biological level during sound baths can be challenging. Goldsby notes that the reasons for the effects of sound are still “primarily theoretical,” but her work and that of others are beginning to offer clearer insights. The sounds and vibrations emitted from the instruments appear to influence brain waves, which vary according to different levels of concentration and consciousness. (Similarly, binaural beats can create a phantom tone in your head to promote focus, relaxation, and cognition.)

Sound baths can provoke and heighten states of relaxation, associated with alpha, theta, and delta brainwaves. Goldsby says the body also seems to experience what researcher Herbert Benson calls a “Relaxation Response” during these sessions.

“The body’s system basically slows down, going out of fight-or-flight and into the rest-and-digest state,” Goldsby said. “Breathing and heart rate slow, muscles relax, and the body returns to its pre-stress state.”

However it happens, sound baths seem to have a noticeable effect. A 2022 study in the journal Religions, (in which Goldsby was involved) exposed 62 participants to a sound bath session and found it “revealed significant correlations between improvements in scores of spiritual well-being and reductions in scores of tension and depression post-sound healing.” These improvements were strongest for participants between the ages of 31 and 40.

Another 2023 paper, published in the European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, exposed a group of 50 participants to Tibetan singing bowls and found significant changes in HPA-related hormone levels, self-reported anxiety, and alpha brainwaves compared to a control group. The researchers concluded that “a single session” was able to “induce a more evidence-based psychological/physiological relaxation response.” Goldsby adds that research has also found sound baths are correlated with reduction in certain measurable brain activity and heart rate variability.

Related Health Stories

Sound baths are an inherently physical experience

A sound bath, from my experience at least, isn’t universally pleasant. The deep, haunting low notes of the gongs seemed to push some of my more unpleasant, thickly buried thoughts to the surface. (Our guide noted that gongs should be avoided by people who may have severe cases of post-traumatic stress disorder.) I also caught myself, for a moment during the peak of the hypnotic experience, feeling as if I had to catch my breath. After the session, I also noticed a kind of persistent nasal drip that caused me to constantly clear my throat. Some participants say this sensation may be due to the vibrations emitted from the instruments actually breaking up mucus in the throat and lungs.

In general, I was struck by just how physical the entire experience felt, something I hadn’t expected from simply reading about the process online. And while I did feel a noticeable sense of serene calm immediately following the session, that feeling seemed to fade within a few days. The lingering veil of general anxious thinking, briefly relieved, slowly crept back in.

Separating sound baths from other meditative experiences

Some of the sound bath’s effects seemed to resemble the altered states of consciousness I’ve previously attained during prolonged mindfulness meditation sessions, albeit more acute and pronounced. When asked about this, Goldsby said several factors make sound healing distinct from meditation alone. Sound baths, she notes, are generally a “passive” experience, whereas meditation is more active.

She adds, though, that “there may be some overlap” between the two. Goldsby also says there may be some placebo effects at work in certain studies but notes that others, notably an influential one out of Chile, that have utilized a randomized controlled trial may have negated that possible effect. Sound baths are also distinct from other musical experiences, such as a loud concert. While the latter may also induce a relaxing sensation, Goldsby notes that such effects are not necessarily achieved without the use of specialized vibrational musical instruments.

“Sound baths specifically utilize vibrational musical instruments (instruments that produce strong vibrations or sound waves), which appears to be the crucial difference in producing stronger positive results for participants,” Goldsby said.

Goldsby admits that research involving sound baths and sound healing practices more broadly is “still in its infancy,” and that academics have only “touched the tip of the iceberg” regarding its potential. The growing commercial interest in the practice, along with its popularity in mainstream culture, means we will likely see more studies investigating its effects in the near future.

Goldsby, for her part, says she plans to continue her research, with a particular focus on physiological effects such as brainwaves and biomarkers of stress and tension. And while I’m not necessarily chomping at the bit to rush into another sound session, I’m certainly glad I did it, and pleased to have had some of my deeper reservations proved wrong.

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.