About half of us will use them at some point in our lives. But few of us like to talk about them, at least in public. With good reason—they were designed to hide something historically associated with dirt, evil, and even death.

“Contact with [menstrual blood] turns new wine sour,” the Roman author Pliny the Elder opined in 77 AD. “Crops touched by it become barren.”

This stigma around menstruation overshadowed the development, use and discussion of period products for hundreds of years, complicating the work of historians who have since studied how our ancestors managed their monthly flow.

“How do you understand things that aren’t meant to last?” asks Sharra Vostral, professor of communication studies and author of Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology. “Sometimes literature has little references. But mostly it’s in letters, reading between the lines and word of mouth.”

Vostral points out that periods were much less common centuries ago—near-constant pregnancies and lactation left little time for monthly bleeding. This relative rarity could be handled with homemade products, including softened papyrus in ancient Egypt, natural sea-sponge in Greece, and buffalo skin among native Americans. For Europeans and American settlers, the most common solution was washable rags.

19th century innovations in menstrual products

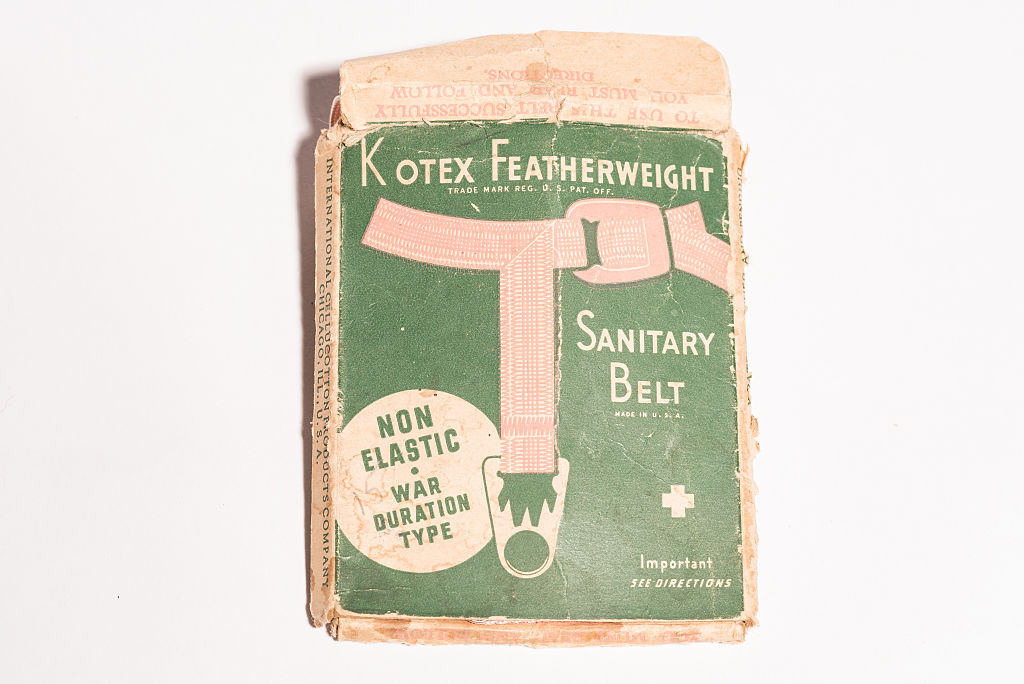

It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that falling birth rates coincided with a push towards more technological, advanced products. The 1850s saw the launch of the sanitary apron, featuring rubber bars and fabric layers to prevent bleeding onto clothes. The design later evolved into the sanitary belt, with clips to hold absorbent cloths in place.

“They wrapped between your legs up to your belly button and were connected to a waistband,” Vostral explains. “They were not easy to manage.”

Stigma held back practical innovations. When Johnson & Johnson brought out the first disposable pads for sanitary belts in 1896—cotton and gauze creations called “Lister’s Towels”—they flopped because women were too embarrassed to buy a product that told the world they were menstruating.

How WWI led to the first pads

A pivotal moment came in World War I, when nurses realized that cellulose bandages were also effective at soaking up other kinds of blood. This innovation inspired the first commercially successful period pads—Kotex Sanitary Napkins, which the Kimberly-Clark Corporation brought to market in 1918.

“It followed a mindset that disposing things is a modern way to manage life,” Vostral says.

Kotex’s success inspired Johnson & Johnson to try again to crack the menstruation market. In 1927, they hired psychologist Lilian Galbraith to research women’s needs for period products. She heaped scorn on bulky pads of the past, explaining that women wanted freedom to live as if they weren’t menstruating at all.

Galbraith’s insights started the push towards smaller, more discreet products, and schemes to reduce the shame of buying them. Johnson & Johnson’s Modess brand introduced magazine coupons that could be pushed across the counter without asking for menstrual pads out loud. The product would be handed over wrapped in newspaper.

“There’s no good that can come from revealing you’re having your period,” Vostral says. “There’s a lot of problematic ideologies.” There was a belief during this era that women “should be in bed” during their period because a menstruating woman was deemed “not reliable.”

The first tampons hit the market in 1930s

In 1931, Earle Hass took discretion to the next level, patenting the first internal product, the menstrual tampon. Although similar designs had been used previously to deliver vaginal medicines, Hass’s reimagined tampons came with a disposable cardboard applicator allowing for easy self-insertion.

Hass sold the patent to Gertrude Tendrich in 1933, who built the product into the renowned Tampax brand. Four years later, actress and entrepreneur Leona Chalmers patented the first menstrual cup, made from rubber. But internal products faced an uphill battle.

“As virginity was highly valued and controlled by men, tampons were seen as potentially a problem,” says Lara Freidenfelds, health historian and author of The Modern Period: Menstruation in Twentieth Century America. “What if that breaks the hymen? Is she really a virgin? What if she finds that pleasurable?” Due to these fears, “using tampons was a little edgy in the 1930s and continued to be for a long time.”

Related History Stories

Lip balm’s surprising history from earwax to Lip Smackers

Ketchup was once a diarrhea cure

The radioactive ‘miracle water’ that killed its believers

How WWII made Hershey and Mars Halloween candy kings

When the U.S. almost nuked Alaska—on purpose

How WWII helped make tampons more accepted

It took another world war to bring about the next transformation—not in products, but in attitudes. With men at the battlefront during World War II, women had to maintain factory production.

“That’s when tampons became more acceptable,” Vostral says. “The idea was that if you’re using a tampon, you wouldn’t have to stay away because of your leaky body or messy pads,” she says. “It helps you stay on the industrial clock.”

After WWII, female inventors started to stake their own place in the menstrual market, battling against entrenched discrimination. In 1957, African-American inventor Mary Kenner patented an adjustable sanitary belt with a built-in moisture-proof pocket. She had first designed the product in the 1920s, when it could have transformed the market. But racism towards Black inventors meant her invention was not commercialized until the 1960s. By then its usefulness was short-lived. Stayfree introduced the first adhesive pads in 1969, quickly making the sanitary belt obsolete.

Pads, tampons, and menstrual cups updated for the 21st century

Throughout the 1970s, a new wave of feminism allowed more open advertising and tweaks to period products, from pads with wings to mini and maxi products for different flows. Tampons suffered another setback, when Procter and Gamble’s 1975 design for a super-absorbent tampon led to a surge of cases of Toxic Shock Syndrome. The product was withdrawn in the 1980s. By 2000, tampons were used by 80% of Western women.

In 2002, Su Hardy created the Mooncup—a reinvention of Leona Chalmer’s menstrual cup that had flopped decades earlier. The new design is made of silicone, making it lighter and more comfortable. But its newfound popularity also speaks to another cultural shift. “The cup now resonates with ideas about environmental sustainability,” Vostral says.

A move away from disposable culture has coincided with a reduction of shame around menstruation, making women willing to reengage with reusable products that require direct contact with their own menstrual blood.

“Recently, the interesting invention is menstrual underwear,” Freidenfelds says, referring to new lines of washable period panties. “I wasn’t confident people would be ok with rinsing underwear rather than simply throwing away a tampon. But it appears they are easy enough to care for that they are getting a sizeable audience.”

While these latest designs might seem to be taking period products back to their origins, Freidenfelds sees these female-led innovations as reflecting a more progressive ideology.

“We’ve inched closer to a radical feminist ideal of menstruation being something that is completely in the open,” she says. “A declaration that this should not be taboo.”