Supernovas are the largest explosions humans have ever observed. They can occur when massive stars run out of fuel and die, shining extremely bright and sometimes leaving behind a mysterious black hole.

Nowadays, scientists armed with sophisticated telescopes witness many supernovas every year, but they have all been distant explosions in galaxies outside of our own. To study supernovas that have taken place closer to home, astronomers can also turn to an unexpected source—historical documents.

“The last explosion in our galaxy that was better observed was before the invention of the telescope. Another observation was in 1604,” Ralph Neuhäuser, a researcher at the Astrophysical Institute at the University of Jena in Germany, tells Popular Science. “There are a few more, like up to 10 historical supernovas that have been observed by humans around the world with the naked eye before the invention of the telescope.”

While the observers that recorded these historical supernovas probably had no idea what they were witnessing, their testimonies can still reveal telling details about these astronomical events—such as where in the sky they took place. This kind of data can help astronomers track down their leftovers, or supernova remnants.

So, how do we know that these historical sources are talking about a supernova rather than some other astronomical events, like shooting a star or a meteor shower? A supernova’s tell-tale written signs usually include the writer mentioning a new and unusual bright star in the sky, sometimes along with its brightness, color, location in the sky, and/or how long it lasted.

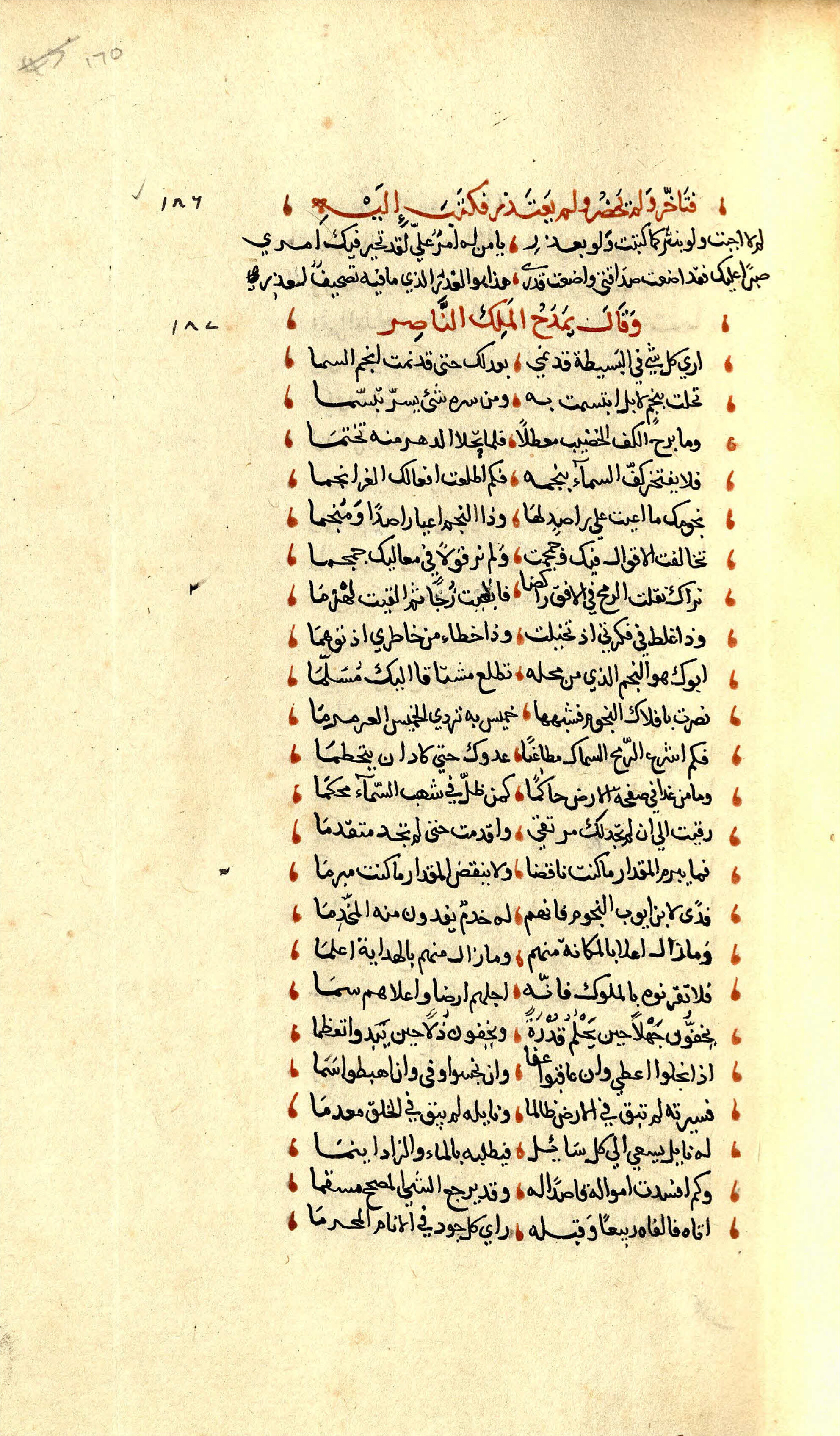

In a study recently published in the journal Astronomical Notes (or Astronomische Nachrichten), Neuhäuser and his colleagues investigate historical supernovas mentioned in two medieval Arabic texts from Cairo, Egypt. One is a poem by Ibn Sanā’ al-Mulk praising Saladin (a famous Muslim sultan of Egypt and other regions) written between 1181 and 1182. The other source is a chronicle by Egyptian scholar Aḥmad ibn ‘Alī al-Maqrīzī, who lived between 1364 and 1442 BCE. Historical records from both China and Japan also describe a supernova in 1181, but the details on its location in the sky are imprecise, meaning astronomers today are unsure which of several supernova remnant candidates resulted from the historical event.

To glean more, Jens Georg Fischer, a study co-author and a graduate student in Arabic and Islamic studies at the University of Münster, asked Neuhäuser to take a look at the poem about Saladin. Neuhäuser confirmed that the text, “is really an observation of that particular supernova, and indeed, there are new details on the position on sky, and possibly also on the duration and the brightness of the supernova.” According to the poem, the “new star” appeared in the henna-stained hand, an Arabic constellation also known as Cassiopeia.

Part of the difficulty in reconstructing the 1181 event is that rather than a supernova, it may have been a different kind of cosmic explosion. The mystery would be solved if astronomers could pinpoint the event’s centuries-old traces. While the Saladin poem doesn’t definitively determine the situation, it does provide a helpful additional constraint.

The supernova mentioned by Al-Maqrīzī, on the other hand, is a completely different situation. The text describes a historical supernova that took place in 1006 BCE. Since this celestial event and its leftovers are already well-known, the description provides very little new astronomical information.

“This was the brightest in the last 2,000 years,” Neuhäuser explains, comparable to the moon. “Very, very bright and so therefore, also relatively nearby.” It took place inside our galaxy, and at just 6,000 light years away, it is the closest known historical supernova.

It goes to show just how consequential ancient sources can be, reaching far beyond the limits of history.