It was as if his muscle memory had evaporated. Twenty-year-old Ethan White couldn’t remember how to use the drumsticks. The snare drum he knew like a part of his own body was suddenly a foreign object. His right hand felt weak, the University of Michigan student thought perhaps it was just fatigue. After all, the Michigan Marching Band had just finished a busy football season with a victory at the 2024 CFP National Championship Game in January. By mid February, Ethan started to notice other odd things—tripping while going up stairs, struggling to hold things in his hands.

In March, an MRI found a tumor on his thalamus, deep in the center of his brain. Ethan was diagnosed with diffuse midline glioma (DMG), a cancer that is a death sentence for the vast majority of people who get it. DMG refers to cancerous tumors that grow on the thalamus, brainstem, or spinal cord. Surgery is out of the question, since these parts of the brain are dangerous to operate on, making it one of the most challenging cancers to treat.

Primarily affecting children and young adults, DMG has an overall survival rate of only 1 percent. Patients are usually given nine to 12 months to live. While DMG’s prognosis has been grim for decades, patients like Ethan are finally starting to see that change.

Using a biological flashlight

A new FDA-approved treatment called Modeyso is giving patients with DMG more time—adding months, even years, and with quality of life intact. It’s “the first change in standard of care in 60-plus years,” Lisa Ward, co-founder of Tough2gether Foundation, tells Popular Science. Her son Jace passed in 2021 from diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma (DIPG), a form of DMG. “It’s the first step and a whole new trajectory of hope.”

Modeyso’s journey into a treatment began a few decades ago. After losing his mother to cancer, Modeyso developer Dr. Joshua Allen became fascinated by cancer defenses that already exist in the human body.

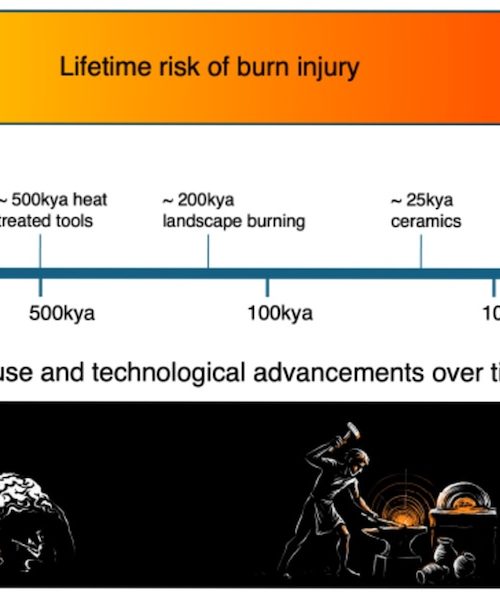

“Evolution has been working on the cancer problem for a long time, a lot longer than humans,” Allen tells Popular Science. “We all get cancer multiple times throughout our lives. Evolution has given the human immune system ways to recognize and get rid of tumor cells. There’s this really cool stuff in immune cells that can kill tumors but doesn’t cause side effects.”

Allen wanted to find a way to bottle this. He began looking for a molecule that could trick tumors into self-destructing. In his research, he used bioluminescence, a tool scientists often use to track how well a cancer treatment is working. The illuminating luciferase gene is the same gene that makes fireflies light up. For Allen, having grown up in Georgia catching fireflies in bottles with his brother, this was full-circle.

The lab inserted the firefly gene into a TRAIL gene. TRAIL genes are naturally produced by our bodies, and selectively trigger cell death in cancer cells. The fusion of TRAIL and luciferase became a biological flashlight, making cancer cells glow. Whenever a cancer cell turned on the TRAIL gene, it also made luciferase, allowing scientists to detect TRAIL-expressing cells by their bioluminescent signal.

The missing puzzle piece

At the same time, bereaved families were donating the bodies of their deceased children to medical research in hopes of finding new treatments, resulting in experts finding an important mutation they didn’t previously know of. Called H3 K27M, the mutation was present in 70 to 90 percent of the children who had died of DIPG. Scientists realized it was also present in other midline brain tumors.

This was the missing puzzle piece for Allen and his colleagues. H3 K27M damages a key “off switch” for genes, causing widespread, uncontrolled gene activity that keeps cells in a multiplying state that causes tumor growth.

Now, Modeyso reverses that mechanism. The once weekly dose is in pill form, and can be taken by patients over age one. Allen is calling it “hope in a bottle.” And while it’s not a cure, the drug is helping to extend patients’ lives with very few side-effects.

“It’s the first big win, to be able to have more time,” Tammi Carr, co-founder of ChadTough Defeat DIPG Foundation, tells Popular Science. Carr lost her five-year-old son Chad to DIPG a decade ago.

“When you get a diagnosis like this, you’re told your child has nine to 12 months to live. Every minute matters, and so to be able to have more time is a huge win from a family’s perspective,” Carr says.

Twenty-year-old Jace Ward started taking Modeyso after his diagnosis in 2019. The young athlete got 17 months that he wouldn’t have had otherwise before he died in July 2021.

“The drug worked very well for him,” says Jace’s mother Lisa. “For 17 months, he could play basketball, golf—he could have Christmas and meet his nephew for the first time. All of these memories got made because, instead of six months, he had 17 good months.”

And sometimes, the treatment works even longer. Thirty-nine-year-old Ben Stein-Lobovits has been taking Modeyso for seven years. Eight years ago, he was at a wedding in Chile when he chalked up the numbness on his tongue to a hangover. Soon after, an MRI showed he had a brainstem glioma. After radiation, he started taking Modeyso.

“I think I’m the longest running patient on it,” Stein-Lobovits tells Popular Science. The father of two has seen a 70 percent reduction in his tumor size, according to his most recent imaging. He now advocates for patients getting on Modeyso as early as they can.

“The earlier the intervention, the better,” he says.

For people with cancer, more time means holidays, family bonding, and milestones. But it also means possibly being around for when there is a cure. The medicine’s minimal side-effects make it easy to combine with other treatments as well.

The gift of normal

In June 2024, four months after his eerie moment with the snare drum, Ethan started taking Modeyso. He had completed 30 sessions of radiation that helped to shrink his tumor, and his family and doctors saw an opportunity to layer the new drug with a few other medications to keep the tumor at bay.

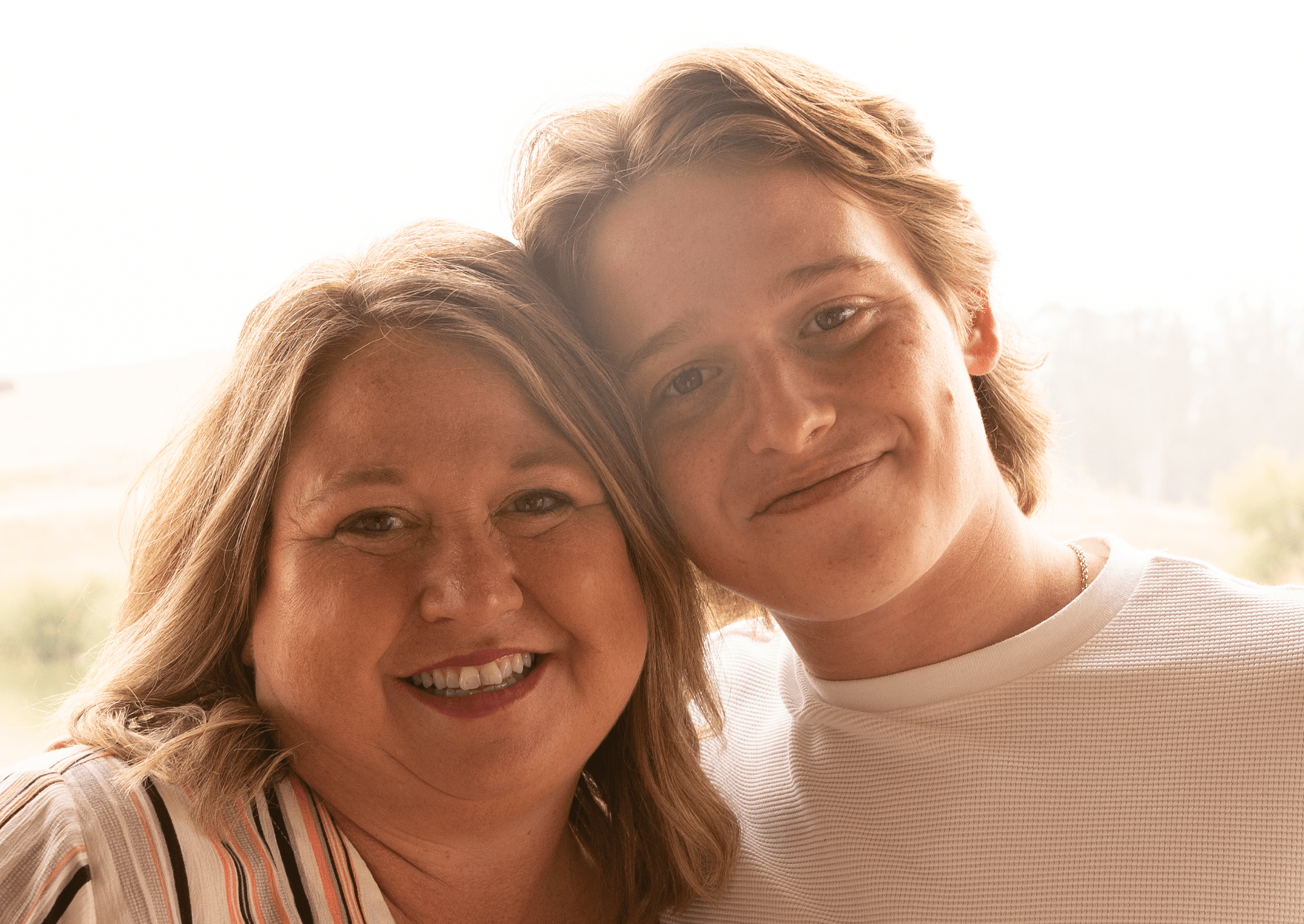

“Having access to [Modeyso] was a major part of keeping him alive,” Ethan’s mother Michelle Sherman tells Popular Science.

Ethan was able to live a relatively normal college life for over a year after that—rock climbing, going to class, living with friends. Sherman says it’s given him time and quality of life. Ethan graduated with honors from the University of Michigan on December 14, 2025.