Some of the solar system’s most distant comets can be very confusing. Many contain crystalline silicates that only form after exposure to high heat, which doesn’t make a lot of sense to astronomers. These comets spend most of their time inside the extremely cold Oort cloud and Kuiper Belt, at temperatures averaging -450 degrees Fahrenheit. So why the heat-related silicates?

After years of speculation, scientists finally believe they have figured out the crystal conundrum thanks to new imaging from NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). Their explanation, detailed in a paper published this week in the journal Nature, indicates the answer resides near a distant, young star about the same size as our sun.

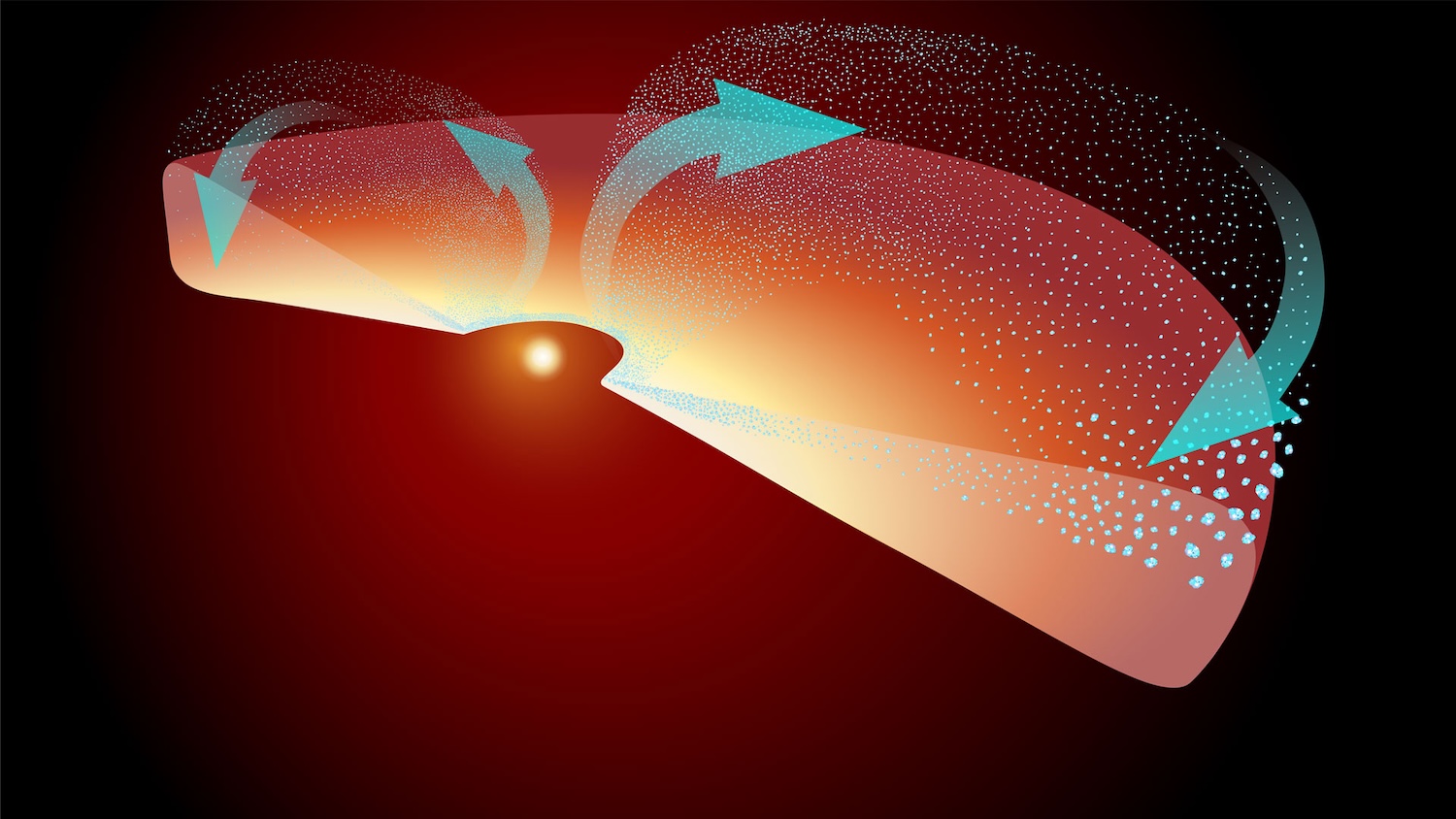

EC 53 is only one of thousands of protostars forming inside the Serpens Nebula about 1,300 light-years from Earth. Like its many siblings, EC 53 is encased by extremely hot dust and gas—exactly the type of environment capable of forging crystalline silicates. It’s also temperamental. After around 18 months of relative calm, the protostar starts a roughly 100-day feeding frenzy in which it inhales the surrounding dust clouds. Meanwhile, outflow jets purge some of this material out to the edges of its protoplanetary disk.

After aiming the JWST’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) towards the protostar, astronomers identified and mapped the locations of certain materials during EC 53’s active and dormant cycles. They soon noticed crystalline silicates like forsterite and enstatite don’t remain near their stellar birthplace. Jeong-Eun Lee, a study co-author and astronomer at South Korea’s Seoul National University, now believes EC 53 and similar protostars toss their newly created silicates into deep space during these meal times.

“EC 53’s layered outflows may lift up these newly formed crystalline silicates and transfer them outward, like they’re on a cosmic highway,” explained Lee. “Webb not only showed us exactly which types of silicates are in the dust near the star, but also where they are both before and during a burst.”

Doug Johnstone, a study co-author and principal research officer at Canada’s National Research Council added, “Even as a scientist, it is amazing to me that we can find specific silicates in space, including forsterite and enstatite near EC 53.These are common minerals on Earth. The main ingredient of our planet is silicate.”

While EC 53 has been growing for millions of years, the protostar is far from finished. Lee, Johnstone, and their colleagues estimate the protostar may remain surrounded by its dust cloud for another 100,000 years. During all that time, miniscule rocks and debris should continue to to collide and merge into the building blocks of future gas and terrestrial planets. In the end, a new star system similar to the one orbiting the sun will emerge from EC 53—and its ejected silicates may very well be on their way towards their own comets.