Multiple brain implants can now translate a user’s thoughts into words, but a new device is the first-of-its kind to handle two languages. Not only does it allow a paralyzed man to converse in both Spanish and English, but it also potentially provides insights into the nature of human language processing.

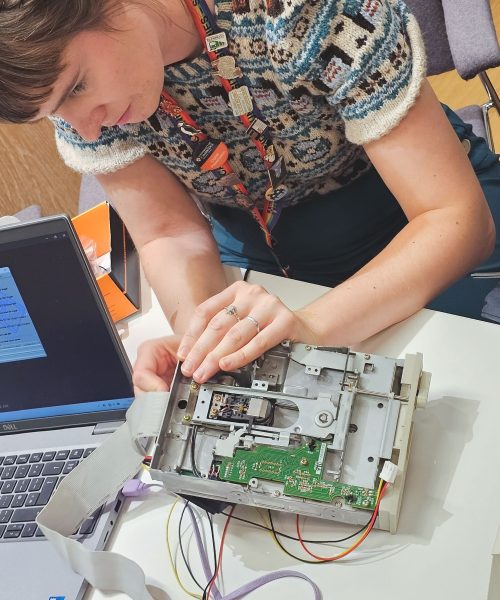

The breakthrough bilingual implant was designed by researchers at the University of California, San Francisco, and detailed in a study published on May 20 in Nature Biomedical Engineering. The team’s advances build off their previous groundbreaking research from 2021, when neuroscientists and engineers surgically implanted electrodes into a man’s cortex to record neural activity, then translated the information into corresponding text on a computer screen.

At the time, however, the patient’s thoughts could only be turned into English. Although the man learned the language as an adult after his debilitating stroke, he is far more familiar and attached to his native language, Spanish.

[Related: 85% of Neuralink implant wires are already detached, says patient.]

“What languages someone speaks are actually very linked to their identity,” Edward Chang, a UC San Francisco neurosurgeon and study co-author, said in his paper’s accompanying announcement. “And so our long-term goal has never been just about replacing words, but about restoring connection for people.”

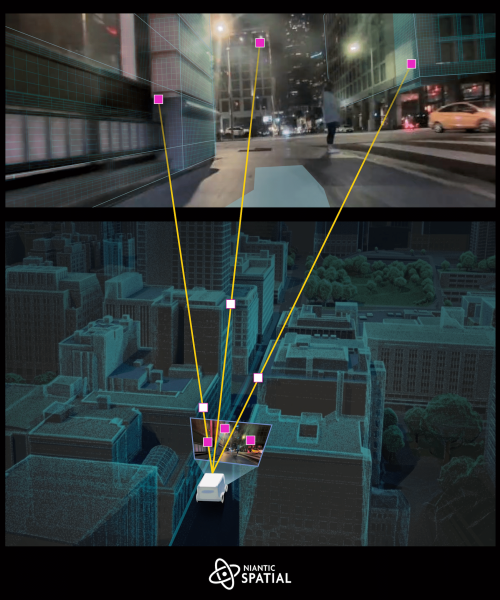

Since then, Chang’s team developed a system that combines artificial intelligence and predictive modeling to interpret the neuroprosthesis data. From there, they trained the program by asking their patient to attempt saying around 200 words while the electrodes transmitted each corresponding neural pattern. Once these were recorded, researchers moved onto the bilingual phase.

The new system is composed of two modules, Spanish and English, each of which attempts to match the neural data of a phrase’s first word in their respective languages. Each module selection is accompanied by an estimated probability of accuracy—the Spanish module may calculate a 50-percent probability the neural activity matches “trabajo” (to work), while the English module assesses an 80-percent likelihood of being the word “they.”

But from there, the AI program shifts tactics. Instead of repeating the first neural-matching step, the modules predict the following words based on probability. Once both English and Spanish sentence estimates were completed, the system displayed whichever phrase possessed the higher overall probability.

By the end of their study, the new AI modules accurately determined the first word’s language 88 percent of the time, while the finalized sentence choices garnered a 75-percent accuracy rate. With additional practice, their patient could even participate in spontaneous conversations with the researchers using the implant’s upgrades.

The additional data appears to contradict previous neuroscience studies that suggested separate brain regions are activated depending on a given language. In this case, however, much of the area-specific activity overlapped for Spanish and English.

There is also evidence that the patient’s neural activity largely mirrored those of people raised bilingual, despite only learning a second language as an adult. Researchers believe this might imply languages share some neurological features, in which case future implant translation technology could be more generalizable. While the brain implant advancements have so far only been studied in one patient, the team hopes to expand the scope for more participants, as well as experiment using other languages.