A new biosensor made out of needles most commonly seen in dermatology clinics and medspas could make the fresh fish “smell test” seem antiquated.

For as long as humans have eaten fish, we’ve identified rot or spoilage by looking for a handful of physical signs. Cloudy eyes, bruised gills, and the unmistakable “fishy” smell are all signs that a piece of salmon might lead to gastric distress or worse. Though relatively effective, these observable signs take time to develop, time during which the fish may already be decomposing. A far more accurate method involves detecting faint traces of metabolic compounds that appear during the earliest stages of spoilage. While that is possible now, these methods typically require large, controlled laboratory settings.

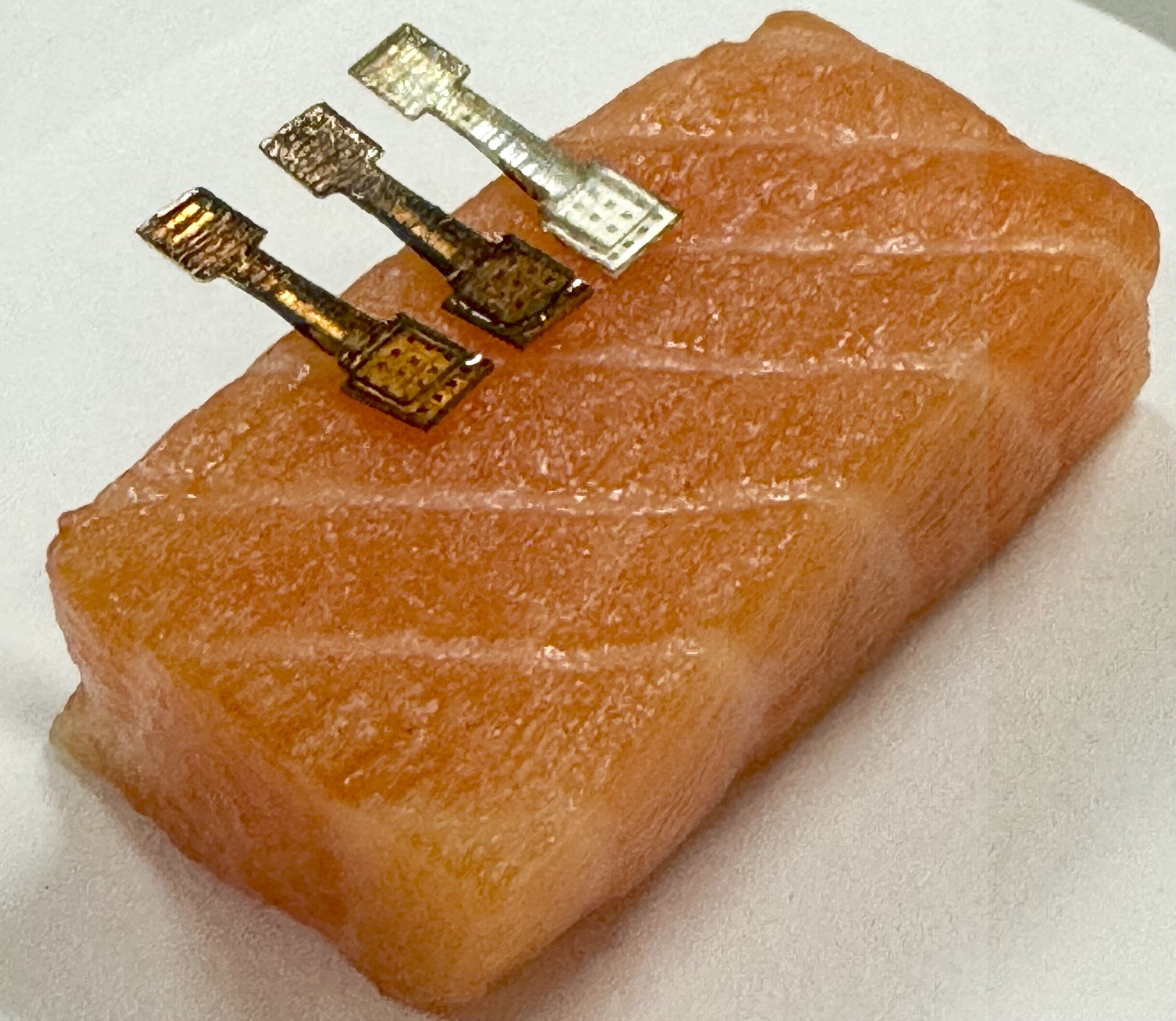

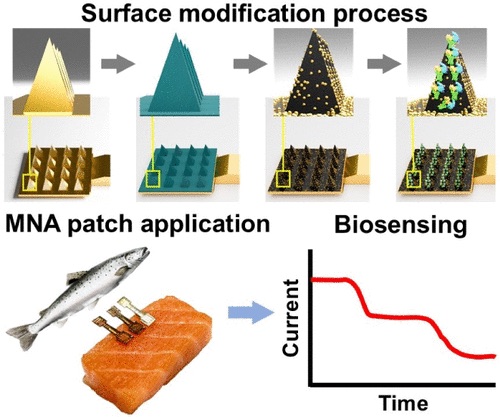

Researchers at the American Chemical Society believe their new “microneedle based freshness sensors” device could make that process much more efficient. Detailed this week in the journal ACS Sensors, the team describes a small device made from an array of microneedles that inserts into a dead fish (or fillets) and continuously measures hypoxanthine (HX), a key compound closely associated with spoilage.

Khazaei et al., ACS Sensors, 2025.

In their experiment, the researchers tested fish samples at varying levels of decay and found that the device could deliver a highly accurate freshness reading in under two minutes. They are hopeful the sensor could bring laboratory-level freshness evaluations to more fish markets—and possibly spare some unwilling victims from having to take a whiff of rotting seafood.

“The ability of the biosensor to monitor HX levels directly in fish samples without extensive pretreatment makes it a valuable tool for assessing fish freshness and quality in real-time,” the researchers write in the paper. “Its portability, fast response time, and ease of use make it ideal for on-site applications in fish markets, processing facilities, and food safety inspections.”

Scientist poked rancid fish with needles

The device is a four-by-four, 3D-printed microneedle array coated with gold nanoparticles. These particles carry an enzyme that can break down any HX compound present when they come into contact with fish. The sensors then measure the resulting changes in the manipulated molecules, a process the team says corresponds to levels of freshness. Some of those early indicators of decomposition notably appear before any physical signs are noticeable to the human eye (or nose).

In the testing phase, the sensor was inserted into fish samples that had been left at room temperature for 0, 6, 12, 24, 36, and 48 hours, the last of which is more than enough time for spoilage to occur. Overall, the researchers observed a, “progressive increase in HX levels over time,” with concentrations rising steadily throughout the entire test period. That consistent uptick mirrors already established results from controlled laboratory studies. At the lower end, the microneedle sensors detected HX concentrations below 500 parts per billion, which is considered “very fresh.” In other words, keeping the sensor in the fish allowed the researchers to pinpoint the moment the sample began to deteriorate.

‘Smart sensors’ could reshape industrial-scale food safety

Sensors of various shapes and sizes are becoming common staples in the increasingly industrialized and high-tech world of global food production. Two years ago, engineers at Koç University in Turkey designed a battery free, smartphone controllable sensor device that can be applied directly to the surface of protein-rich meats like beef to remotely monitor their spoilage rates. Meanwhile, over at MIT, researchers developed Velcro-like food sensors (also made with microneedles) designed to attach to plastic food packaging and detect signs of contamination. In this system, the needles were coated with a bioink that changes color when they encounter fluids with pH levels associated with spoilage. For example, the sensors shift from blue to red when they come into contact with E. coli and other harmful bacteria.

Related: [FDA approves lab-grown salmon]

More recently, researchers at the University of Connecticut developed a machine-learning AI model that analyzes data continuously collected from 12 sensors measuring dairy samples and used it to identify patterns associated with the presence of pathogens. In testing, the model was able to detect eight different pathogens and bacteria that cause spoilage in milk in under two hours, with 98 percent accuracy.

As for the fish sensor, the chemists and engineers developing the device are hopeful it could make a real-world impact in the seafood industry, though it’s not quite ready for commercial use. For now, it is also limited primarily to measuring fish, because the HX spoilage thresholds at the core of its detection method can vary significantly between animal species.

Until then, it looks like the smell test inevitably remains an unpleasant but necessary fallback for most home cooks.