Astronomers have discovered a small exoplanet orbiting Barnard’s star, the closest single star to our sun. This newly discovered exoplanet designated as Barnard b [2] has at least half the mass of Venus and it takes just over three Earth days for it to orbit the sun. Its very existence hints at three more exoplanet candidates in various orbits around Barnard’s star. The findings are detailed in a study published October 1 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

[Related: 1.5 billion cosmic objects dazzle in the largest infrared Milky Way map ever created.]

What is Barnard’s star?

Barnard’s star is a red dwarf about six light-years away from our sun and six light-years away from Earth. It is considered the closest single star and second closest stellar system to us, following Alpha Centauri’s three-star group. It is too dim to be seen with the naked eye despite being so close to us, but can be observed with telescopes.

Red dwarf stars like these are also prime candidates in the search for potentially Earth-like exoplanets. Low-mass rocky planets are easier to detect near red dwarfs than around larger stars like our sun, as these stars have cooler temperatures and a temperate zone that is much closer to the star’s surface than hotter stars like the sun. This means that any planet orbiting the star within their temperate zone orbits it in a shorter period of time. Astronomers can then monitor them over days or weeks, instead of years.

There was one promising exoplanet detection in 2018, also designed as Barnard b, but scientist’s were not able to confirm it. According to the European Southern Observatory (ESO), it’s common practice in science to name exoplanets by the name of their host star with a lowercase letter added to it, ‘b’ indicating the first known planet, ’c’ the next one, and so on.

“Even if it took a long time, we were always confident that we could find something,” Jonay González Hernández, a study co-author and an astrophysicist at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Spain, said in a statement.

Using ESPRESSO to detect an exoplanet

To detect this new exoplanet, scientists used the ESO’s Very Large Telescope (ESO’s VLT) in Chile. They took observations over the last five years. Searching for signals from possible exoplanets within the habitable or temperate zone of Barnard’s star. This zone is the area where liquid water can exist on the planet’s surface.

Barnard b [2] is 20 times closer to Barnard’s star than the planet Mercury is to the sun. It has a surface temperature around 257° Fahrenheit and a full year lasts a little over three days here on Earth.

“Barnard b is one of the lowest-mass exoplanets known and one of the few known with a mass less than that of Earth. But the planet is too close to the host star, closer than the habitable zone,” said González Hernández. “Even if the star is about 2500 degrees cooler than our sun, it is too hot there to maintain liquid water on the surface.”

The team also used an instrument called ESPRESSO (Echelle SPectrograph for Rocky Exoplanets and Stable Spectroscopic Observations) for their observations. This highly precise instrument on the VLT is designed to measure the wobble of a star that is caused by the gravitational pull of one or more orbiting planets.

To confirm these wobbles, the team used the data from other instruments also specialized in exoplanet hunting–HARPS at ESO’s La Silla Observatory, HARPS-N and CARMENES. However, this new data did not support the existence of the exoplanet that was reported in 2018.

[Related: 400 years of telescopes: A window into our study of the cosmos.]

Could there be more?

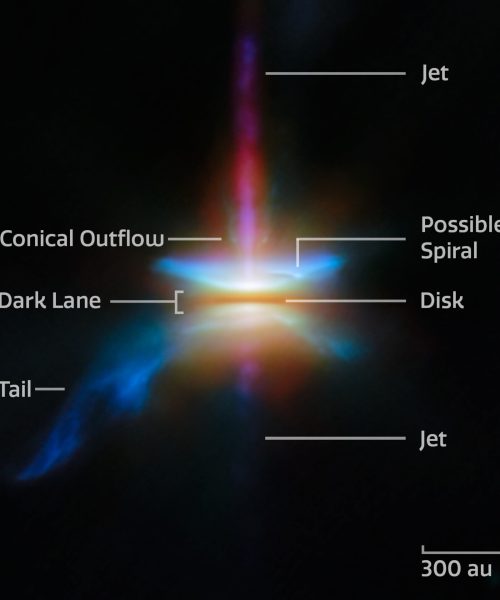

In addition to Barnard b [2], the team found hints of three more exoplanet candidates orbiting this same star. However, observations with ESPRESSO are needed to confirm their existence.

“We now need to continue observing this star to confirm the other candidate signals,” study co-author and Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias astronomerAlejandro Suárez Mascareño said in a statement. “But the discovery of this planet, along with other previous discoveries such as Proxima b and d, shows that our cosmic backyard is full of low-mass planets.”

The ESO’s Extremely Large Telescope (ELT) is currently under construction and is scheduled to be completed by 2028. Astronomers hope that it helps transform the field of exoplanet research, particularly with its ANDES instrument. It should allow researchers to detect more of these small, rocky planets in the temperate zone around nearby stars and study the composition of their atmospheres.