In December 2010, Michael Faherty died in his home in Galway, Ireland. His body was found burned and the fireplace was lit, but there was no other apparent source of flames nearby nor accelerant. The house was largely unscorched. The only damage were soot marks on the ceiling and floor immediately below and above where the 76-year-old retiree met his end. At a loss for an alternate explanation, the coroner chalked Faherty’s death up to spontaneous combustion.

Enlightenment-era clickbait

Such deaths are rare, especially in the 21st century. But in Europe in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, upwards of a dozen cases of supposed spontaneous combustion (and potentially as many as 200, depending on who you ask) were reported or described retrospectively. Most share a few unifying hallmarks. The victims were largely older, overweight women. Often, they were believed to be heavy drinkers or alcohol was present at the scene. The bodies were found with the torso burned away, bones and all, and puddles of a dark, greasy substance left behind, while extremities and immediate surroundings–including furniture were left unmarred.

The grim scenes were frequently written up in tabloid-esque periodicals of the time, says Michael Lynn, a historian of early modernist Europe at Purdue University Northwest. Lynn has researched and published on the spontaneous combustion trend that emerged in his study region and era. Stories of spontaneous combustion were treated akin to sensational oddities that functioned like Enlightenment-era clickbait, he tells Popular Science, often with a heavy dose of exaggeration, moralizing, and hand-wringing over the perceived indulgences of modern living.

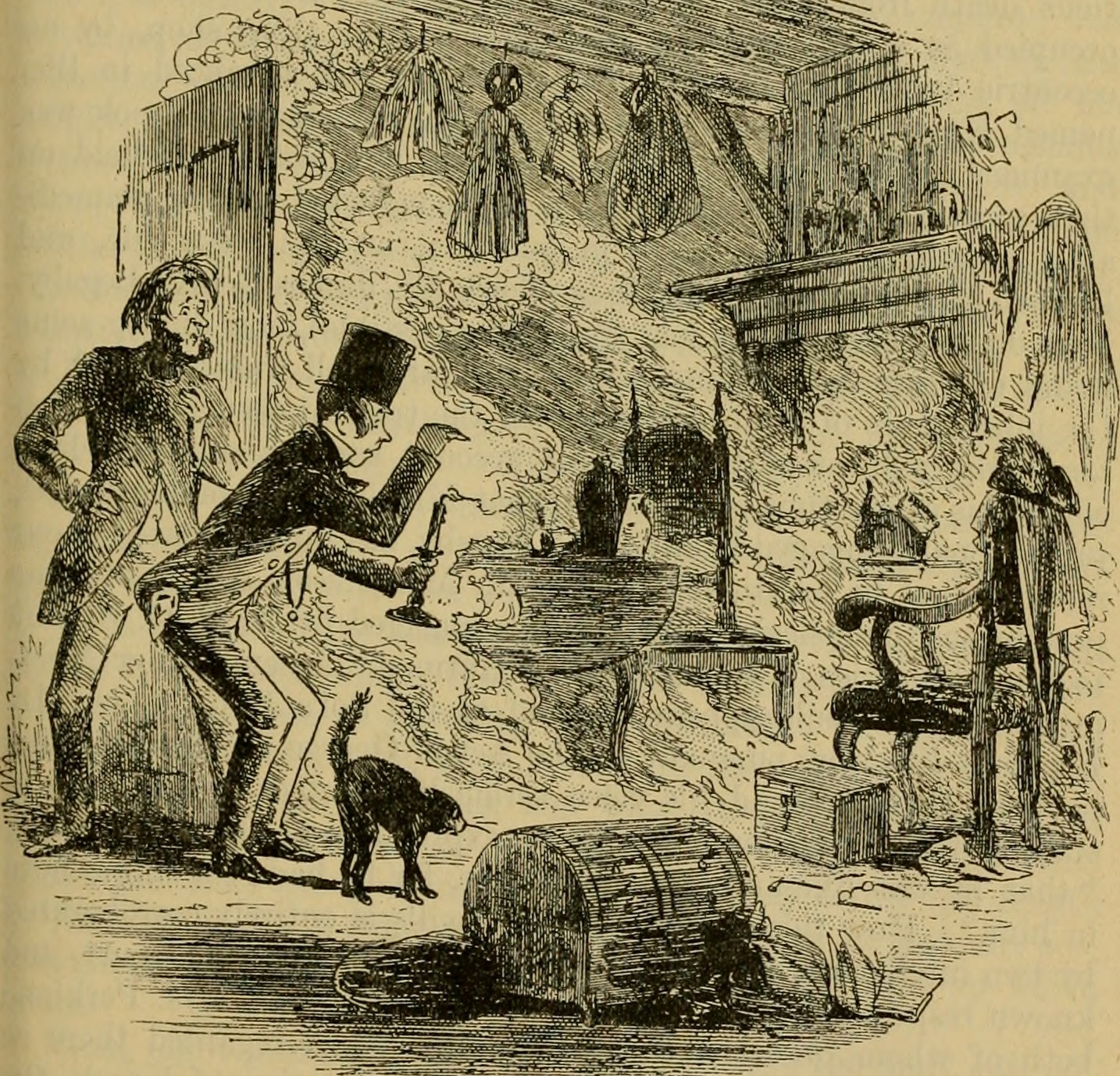

The idea that, at any moment, a living person could burst into deadly flames, permeated the cultural zeitgeist of the time– showing up in literature as well as newspapers. Charles Dickens’ Bleak House is the most famous example. In the story, alcoholic landlord and rag merchant, Krook, leaves only a pile of ash behind when he is consumed by sourceless fire. Herman Melville and Emile Zola also killed off characters through spontaneous combustion. But the phenomenon wasn’t just a convenient plot device. For some, it was a firmly held belief. Dickens included a defense of the possibility, citing multiple alleged real-world reports, in a preface added to an early edition of the book. “I shall not abandon the facts,” he wrote.

But what exactly are the facts behind this fiery phenomenon?

The real science of spontaneous combustion

Scientifically speaking, spontaneous combustion is a real phenomenon. Certain extremely flammable chemicals–like phosphorus–or materials, such as wet hay or compost, can flare up at relatively low ambient temperatures and without any ignition source. Exothermic chemical reactions and accumulating heat from decaying organic matter and fermentation explain the sudden fires. But human bodies are a whole other issue. It’s deeply improbable, nigh impossible that “spontaneous combustion” is a valid explanation for any of the alleged cases, says Roger Byard, a forensic pathologist and emeritus professor at the University of Adelaide in Australia.

“It’s never been witnessed,” Byard tells Popular Science. “If people could spontaneously burst into flames, you’d be down at Walmart and suddenly the little old lady beside you, pushing a trolley would explode.”

[ Related: Charles Dickens’s belief in spontaneous combustion sparked Victorian London’s hottest debate. ]

Instead, the incidents all concern people who die isolated and unobserved. There’s also never been a report in any other animal species, he notes–it’s a strictly human phenomenon. (Although whale carcasses washed up on beaches sometimes “explode,”that’s simply a buildup of gasses from internal decomposition that release suddenly, there’s no intense heat or fire.) In his view, the missing factor is that other animals don’t tend to “wrap themselves up in blankets and drink whiskey and smoke,” he says.

A handful of hypotheses have been proposed for how and why spontaneous combustion might occur in humans, none of which are especially scientifically rigorous nor have been demonstrated. Conspiracists and 19th century scientists alike have blamed acts of God, lightning, trace amounts of phosphates, static electricity, unspecified particles in the blood, and intestinal gases. More recently, an independent researcher suggested acetone accumulation resulting from the metabolic state, ketosis, could explain it.

The wick effect

But one explanation seems far more likely than the rest, and doesn’t really involve any “spontaneous” combustion at all. Instead, Byard thinks the wick effect is the most plausible. “These people are essentially human candles,” he says.

The wick effect describes how human fat burns under blankets and clothing lit with the help of a little bit of accelerant (for instance, spilled liquor), when ignited by a spark or ember. Under these conditions, a fire can burn low and slow, producing hot temperatures, but without high flames and with little collateral damage. If a sleeping or intoxicated person spilled some alcohol on themselves, then dropped a cigarette or caught a stray ember from a fireplace, that could kick off the deadly process.

In 1998, an experiment conducted for a BBC science documentary series demonstrated that the wick effect could replicate the types of scenes found in instances of alleged spontaneous combustion. John DeHaan, a forensic scientist, set fire to a pig carcass wrapped in blankets, and found that it continued to burn for hours. Eventually, the entire midsection of the pig was gone, including the bones, while the less fatty legs remained intact.

It’s not a nice way to go, for a pig or a person. But at least it’s more avoidable than a sudden fiery act of divine punishment or an unforeseen internal gas explosion.

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.