When they aren’t baffling the public or grounding wildfire planes, drones have some pretty solid uses. Apart from unnecessarily fast same-day deliveries, the pilotless aircrafts may soon become a lifesaving emergency response tool. A collaborative team of health experts, community organizations, and universities are in the middle of a pilot program using drones and automated external defibrillators (AEDs). Led by Duke Health and the Duke Clinical Research Institute, EMS responders are now deploying drones AEDs to certain 911 calls in Forsyth County, North Carolina.

Why is cardiac arrest so serious?

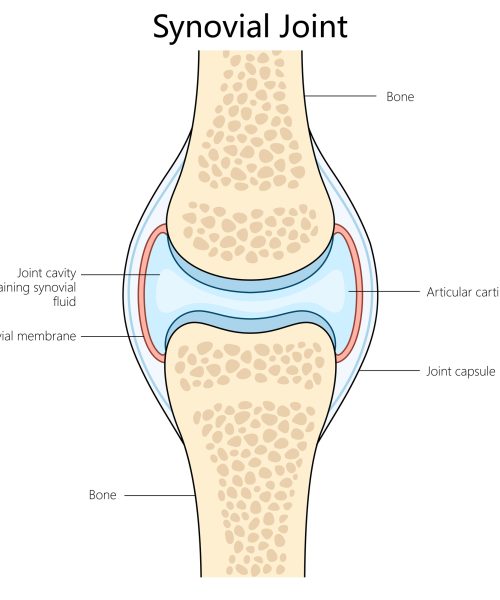

Over 350,000 people experience cardiac arrest every year in the United States. When that happens, time is crucial–and AEDs are key to saving lives. Each device includes external sensor pads that adhere to a patient’s chest to monitor their heart. At the appropriate time, the pads deliver a moderately high voltage shock (usually between 200 to 1,000 volts) to readjust and regulate the heartbeat. Modern AEDs are designed to be used with minimal experience, and often include a speaker in the central component to verbally give proper instructions.

Although 90 percent of patients survive if an AED is administered within the first minute, such a rapid response is often out of the question, unless a patient is already in a healthcare facility. The American Red Cross estimates over 70 percent of all cardiac arrests occur at home, with survival odds decreasing around 10 percent for every additional minute of delayed AED application. The national average for EMS response times is around seven minutes, but in rural areas the timeframe can often extend as long as 13 minutes.

Unlike an ambulance or firetruck, a lowflying drone isn’t beholden to traffic slowdowns or winding streets. Researchers like Monique Starks at the Duke University School of Medicine suspect that deploying drones in conjunction with EMS workers may offer opportunities to provide faster AED deliveries.

“This study represents a major step forward in how we respond to cardiac arrest in the United States,” Starks said in a statement. “By integrating drone technology into emergency care, we’re working to close the critical gap between cardiac arrest and treatment, and that has the potential to save thousands of lives.”

Adding to emergency response

Importantly, the trial does not alter any existing 911 response protocols. When EMS is dispatched to the location, a pilot remotely deploys and guides a drone flying 200 feet above the ground to the same address. If it arrives before first responders, the drone descends to 100 feet and lowers the AED down via a winch strap. At that point, a 911 dispatcher can take a bystander step-by-step through using the device on the person in need.

“They won’t replace traditional response systems, but they can strengthen them by placing lifesaving equipment in the hands of bystanders when it matters most,” added Betsy Sink, James City County Emergency Medical Services battalion chief. “This project allows us to better understand how far this innovation can go in improving survival and will shape the future of emergency medicine.”

The pilot program also includes James City County, Virginia, but could expand to more areas depending on the overall outcome.

“This project is laying the groundwork for what we hope will become a large, multi-center randomized clinical trial,” said Joseph Ornato, an emergency medicine professor at Virginia Commonwealth University and study co-lead. “That future research will help us understand critical questions about how well this works, what it costs, and how we can get AEDs to people as quickly as possible whether they live in a city or rural community.”