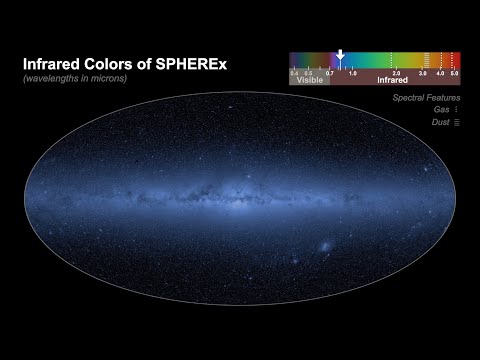

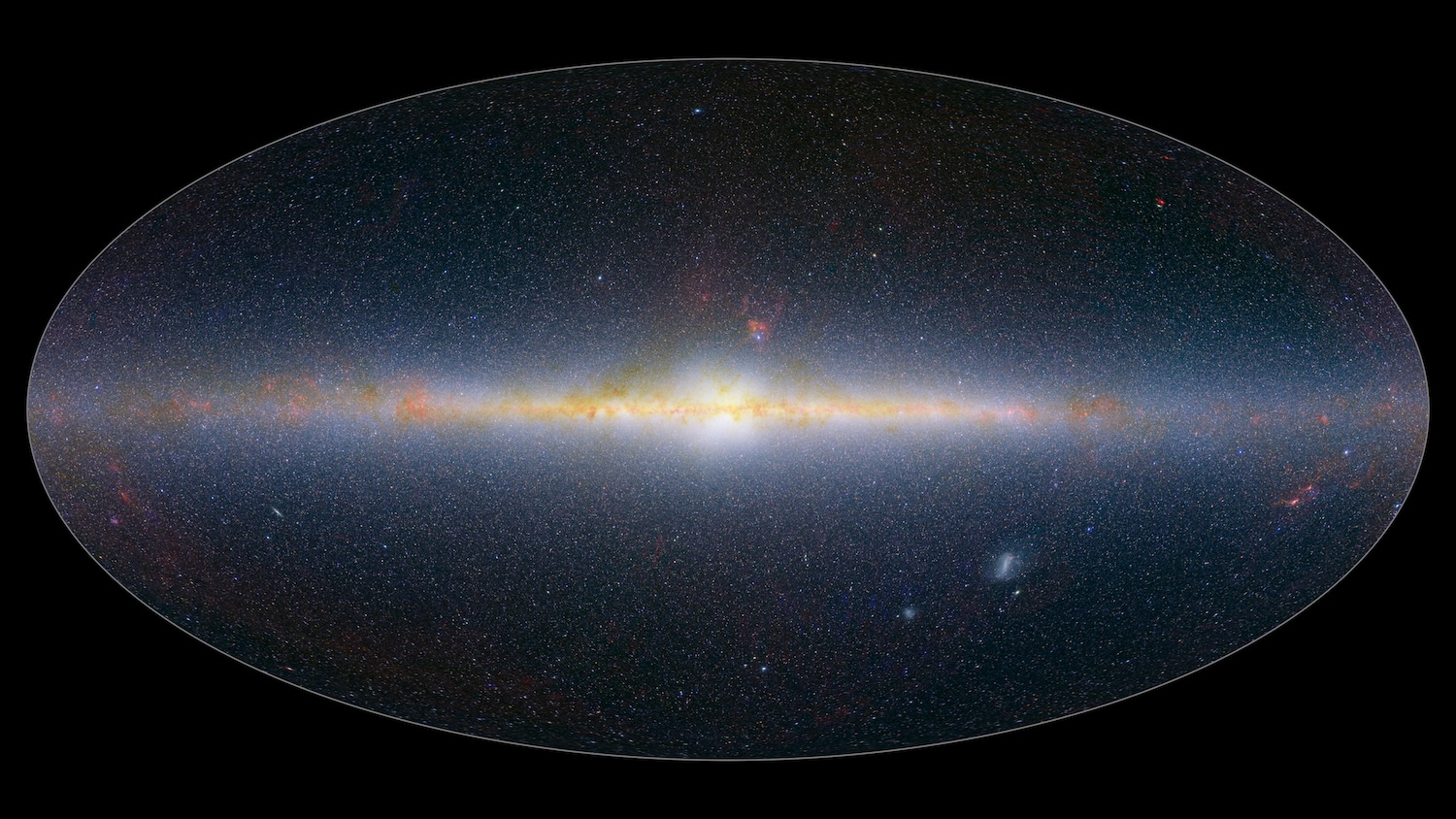

NASA aimed big for its SPHEREx’s first 3D cosmic map. Only six months after starting operations, the orbital space telescope has completed its inaugural infrared scan of the entire sky. Although infrared isn’t visible to the human eye, the map’s 102 wavelengths remain detectable across the universe—to the right instruments. According to NASA scientists, the groundbreaking catalog allows astronomers to peer back in time to the earliest moments of the cosmos

“It’s incredible how much information SPHEREx has collected in just six months—information that will be especially valuable when used alongside our other missions’ data to better understand our universe,” Shawn Domagal-Goldman, director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA, said in a statement. “We essentially have 102 new maps of the entire sky, each one in a different wavelength and containing unique information about the objects it sees.”

With the new trove of data, Domagal-Goldman and colleagues hope to glean new information about the incomprehensibly brief (but massively consequential) first billionth-of-a-trillionth-of-a-trillionth of a second after the big bang. The forces involved in these pivotal moments would ultimately influence how the universe’s hundreds of millions of galaxies distributed themselves across space-time. From there, astronomers can begin to examine how these galaxies evolved over the last 14 billion years.

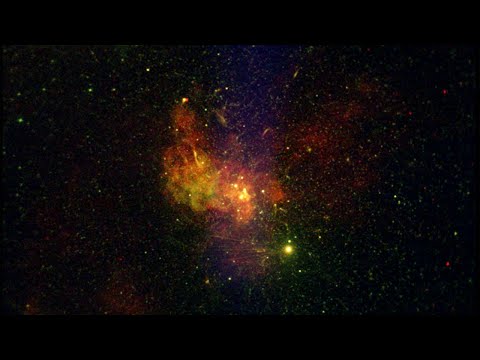

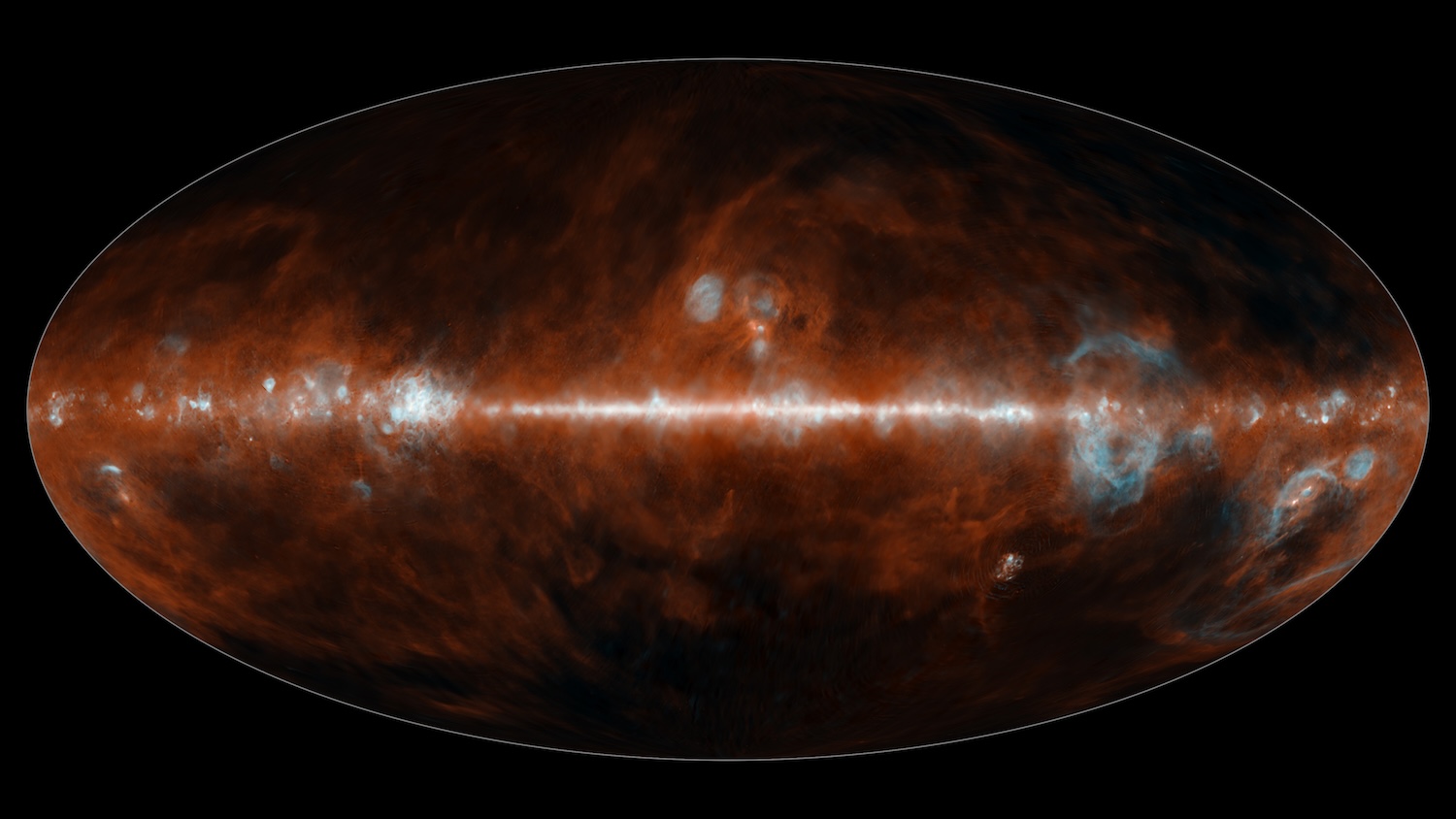

Infrared may not be visible to us, but the wavelengths contain a wealth of vital information. All stars and planets are born inside dense dust clouds, but they don’t radiate the types of light that they human eye has evolved to see. This means that what may appear as a vacant region of the universe to the naked eye is actually a dynamic, creative cosmic nurseries.

Getting to this milestone of infrared spectroscopy was no easy feat. Since May, SPHEREx (short for Spectro-Photometer for the History of the Universe, Epoch of Reionization, and Ices Explorer) has orbited Earth from north-to-south over the planet’s poles at a rate of 14.5 times per day. Over the course of each circuit, SPHEREx amassed around 3,600 images inside a single strip of sky. The telescope’s field of view then shifted naturally over time as Earth continued along its solar orbit. Six months’ later, SPHEREx finally completed a 360-degree survey of the sky.

SPHEREx is uniquely suited for such a vast project. NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer previously completed a similar map, but not in as many wavelengths. And while the James Webb Space Telescope houses far more advanced spectroscopic tools, its technical field of view is thousands of times narrower.

“The superpower of SPHEREx is that it captures the whole sky in 102 colors about every six months. That’s an amazing amount of information to gather in a short amount of time,” SPHEREx project manager Beth Fabinsky said. “I think this makes us the mantis shrimp of telescopes, because we have an amazing multicolor visual detection system and we can also see a very wide swath of our surroundings.”

The observatory’s mission is far from over. From here, SPHEREx’s primary directive will complete another three scans of the entire sky over the next year-and-a-half. From there, researchers will merge all four maps to boost the overall sensitivity of measurements. Both the final project, as well as the current dataset, is available online for free.

“SPHEREx is a mid-sized astrophysics mission delivering big science,” said NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory Director Dave Gallagher. “It’s a phenomenal example of how we turn bold ideas into reality, and in doing so, unlock enormous potential for discovery.”