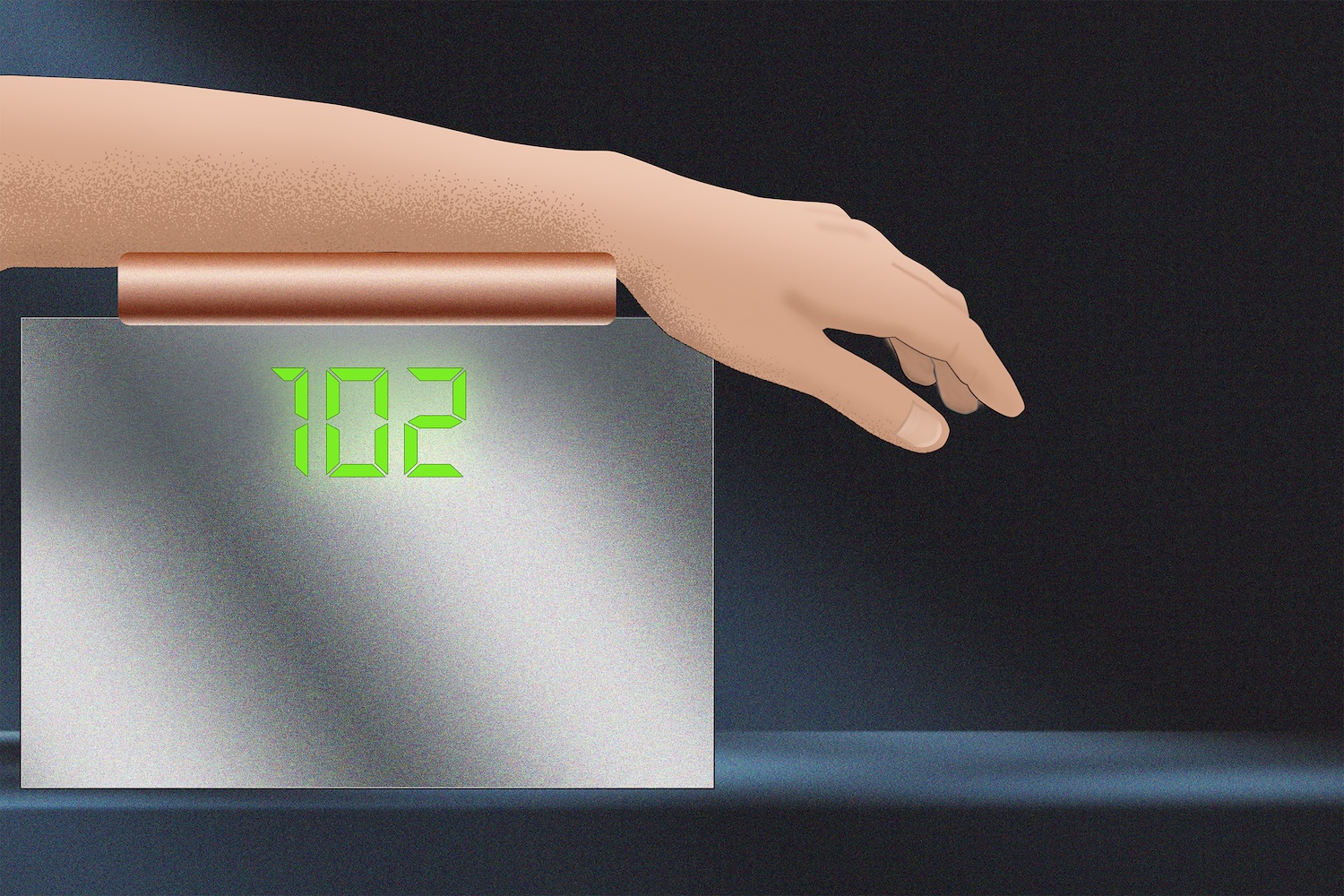

A new, noninvasive blood-glucose monitoring system may allow people with diabetes to finally ditch their painful finger pricks and under the skin sensors. Although the current iteration is comparatively bulky, MIT scientists writing in the journal Analytical Chemistry say they are well on their way to scaling down their invention. In time, their light-based approach could even fit on a device the size of a watch.

Diabetes management requires a person to regularly monitor their glucose levels. For decades, this almost always required multiple, daily finger pinpricks to obtain blood samples. While wearable glucose monitors have risen in popularity in recent years, they still have their own issues. These types of wearables provide constant analysis via interstitial fluid, but only after inserting a sensor wire under the skin. Even then, wearers must replace their sensors every 10 to 15 days, and they still frequently cause irritation.

“Nobody wants to prick their finger every day, multiple times a day,” MIT research scientist and study co-author Jeon Woong Kang said in a statement, adding that this issue goes beyond someone’s pain tolerance. “Naturally, many diabetic patients are under-testing their blood glucose levels, which can cause serious complications.”

For this new way to monitor blood sugar without the pinpricks, Kang and colleagues are building on research stretching back over 15 years. Biomedical engineers at MIT Laser Biomedical Research Center (LBRC) medical engineers first demonstrated they could noninvasively calculate glucose levels in 2010 using Raman spectroscopy, a technique that uses light particles to examine and identify molecules. In this instance, scientists used a device that shined near-infrared and visible light on organic tissues. They then compared the resultant Raman wave signals bouncing off skin cells’ interstitial fluid to reference glucose levels. While accurate, the method wasn’t practical for daily use.

The possibility of harnessing Raman signals became much more viable after researchers designed a workaround to their problem. In 2020, the LBRC announced that they could pinpoint glucose signals by simultaneously firing Raman signals at tissue while also shining near-infrared light from a different angle. This approach filtered out the signals from unrelated skin molecules, allowing engineers to locate and monitor glucose information.

Although the original Raman glucose monitor was about the size of a printer, they have since shrunk the overall device down to the proportions of a shoebox. To do this, they identified only the Raman bands that are needed to measure glucose in the blood.

“By refraining from acquiring the whole spectrum, which has a lot of redundant information, we go down to three bands selected from about 1,000,” explained researcher and study co-author Arianna Bresci. “With this new approach, we can change the components commonly used in Raman-based devices, and save space, time and cost.”

Each measurement scan takes slightly more than 30 seconds to complete. The device also shows an accuracy comparable to two commercially available, wearable glucose monitors.

“If we can make a noninvasive glucose monitor with high accuracy, then almost everyone with diabetes will benefit from this new technology,” said Kang.

As they continue scaling down their Raman glucose scanner, researchers will also focus on additional clinical and larger study tests to ensure the technology’s feasibility, as well as its ability to scan across all skin tones.