The evidence is clear—and in your hair. Americans were exposed to as much as 100 times more lead in their daily lives than they are today before the Environmental Protection Agency was established in 1970. In an effort to examine the dramatic reduction in toxic heavy metal exposure, researchers turned to human hair samples dating back a century. Their findings, published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, provide a startling and dramatic example of the lifesaving benefits of robust, comprehensive, and reliably enforced industrial regulations.

Human history is full of lead poisoning. Paleobiological records indicate that the naturally occurring neurotoxin has affected Homo sapien’s evolutionary development for at least two million years. While no amount of lead exposure is healthy, even comparatively moderate levels of ingestion are directly linked to brain development issues, behavioral shifts, heart and organ damage, pregnancy complications, and immunosuppression problems. These hazards are also particularly dangerous for infants and children.

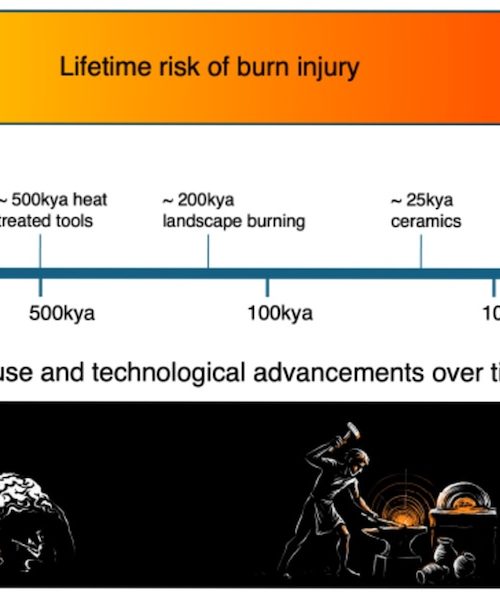

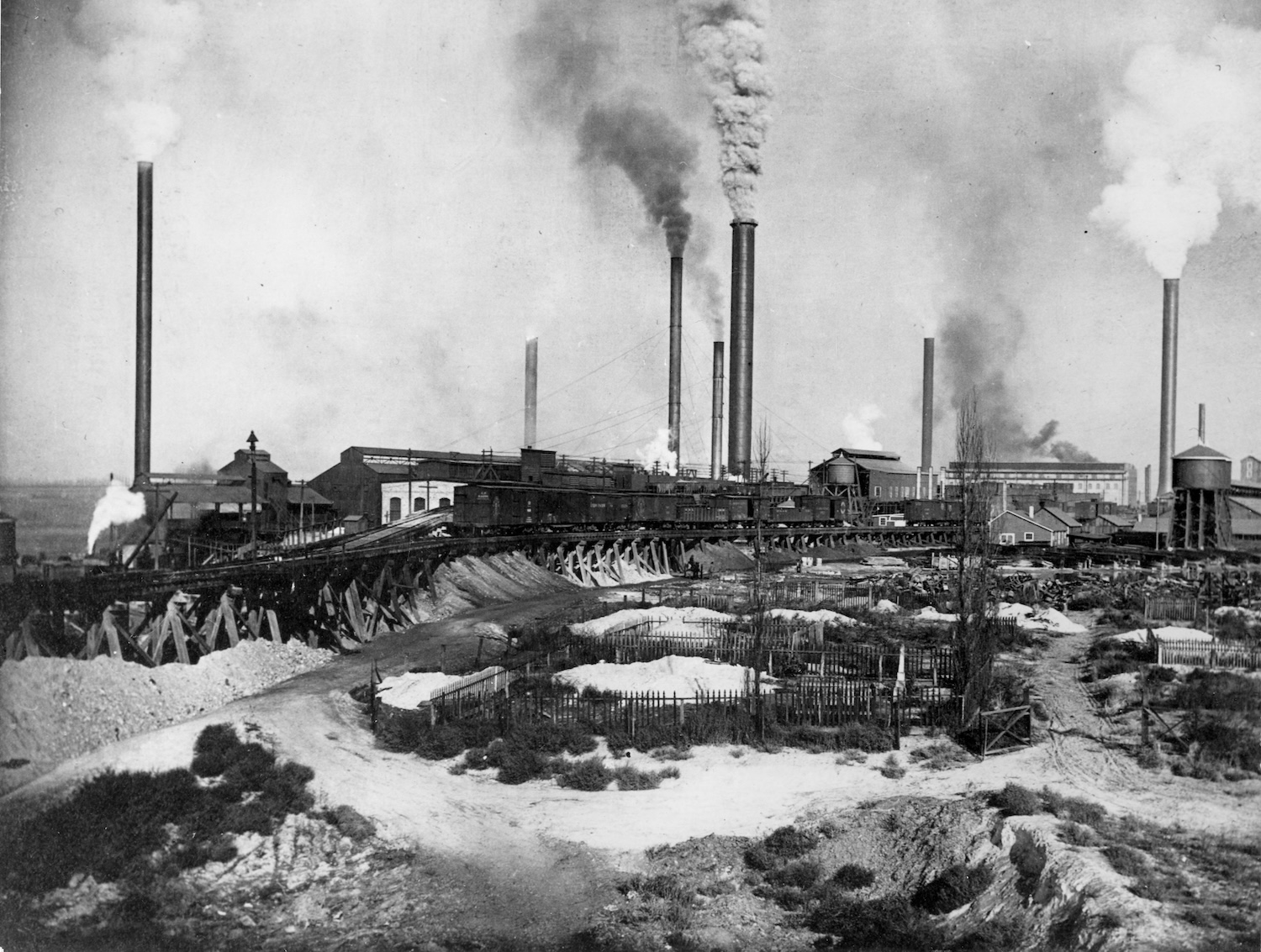

Our species only faced more danger from lead as our technology advanced. Common items including cookware and plumbing components likely affected cognition and physical health in ancient Rome—and these issues became exponentially more dangerous amid the modern manufacturing era. Mounting scientific evidence and sustained public health advocacy finally resulted in the EPA issuing strict rollbacks on lead usage during the 1970s. But even as recently as 1978, the poison could regularly be found in everyday products like paint, pipes, and gasoline.

While lead contamination is still a major issue, its overall reduction is apparent only a few decades after EPA policy regulations were implemented. To understand how much, a team from the University of Utah and the National Institutes of Health recently used mass spectrometry to measure lead levels in human hair. While blood is considered a better biomaterial to assess, hair is still incredibly helpful to study because it’s easier to collect and preserve.

“The surface of the hair is special. We can tell that some elements get concentrated and accumulated in the surface,” explained University of Utah geologist and study co-author Diego Fernandez. “Lead is one of those. That makes it easier because lead is not lost over time.”

Fernandez and his team previously studied blood samples and family health histories of Utahns. This time, the team recruited volunteers from the Wasatch Front region in northern Utah to provide hair samples. These participants were especially interesting to the researchers because they lived in a region of the state known for its history of industrial runoff—as well as its significant Mormon population and their extensive genealogical records.

“The Utah part of this is so interesting because of the way people keep track of their family history. I don’t know that you could do this in New York or Florida,” said study co-author Ken Smith, a family and consumer study researcher.

In total, the authors received the hair samples of 48 individuals from various stages of their lives, as well as from some of their distant relatives dating back to 1916 from archival sources like family scrapbooks. The mass spectrometry data illustrated dramatic changes over 100 years. Prior to the closure of regional smelting facilities and EPA regulations, Utah residents ingested around 100 times as much lead as they do today. The dramatic decrease also directly aligned with the reduction and eventual removal of lead from gasoline. Before 1970, gas typically included around two grams of lead per gallon, tallying up to about two pounds of lead released into the atmosphere per person every year.

“‘It’s an enormous amount of lead that [was] being put into the environment and quite locally,” said study co-author Thure Cerling, who works in both geology and biological research. “It’s just coming out of the tailpipe, goes up in the air and then it comes down. It’s in the air for a number of days, especially during the inversions that we have and it absorbs into your hair, you breathe it and it goes into your lungs.”

While gas consumption continued to rise in the ensuing decades, lead samples in hair dropped sharply. Samples from the 1970s measured as high as 100 parts per million (ppm), but by 1990 they lowered to 10 ppm. In 2024, the amount averaged only 1 ppm.

Recent Trump administration announcements have severely carved away EPA regulatory powers, worrying scientists, environmentalists, and everyday Americans. The study’s authors stress that their latest findings provide some of the clearest objective evidence of the benefits of sensible ecological oversight.

“We should not forget the lessons of history. And the lesson is those regulations have been very important,” said Cerling. “Sometimes they seem onerous and mean that [an] industry can’t do exactly what they’d like to do…But it’s had really, really positive effects.”