Every year, Hershey manufactures 373 million of its signature milk chocolate bars. While the company doesn’t release exact stats on Halloween sales, you can bet a lot of those end up in plastic Jack O’Lantern-shaped pails. Hershey’s also produces a few other Halloween heavy-hitters in similarly staggering quantities, churning out 25 million Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups and 70 million Hershey’s Kisses a day. But last year, Mars Inc. gave Hershey a run for their money when M&Ms overtook Reese’s as that year’s most popular Halloween candy. Mars makes a whopping 400 million of the sugar-coated candies daily.

A few different factors have helped Mars and Hershey maintain their Halloween aisle hegemonies year after year. There’s the nostalgia element: Parents often want to give their kids the same candies they loved when they were small. There’s the fact that both companies go hard on convenient, single-serving packaging, often in festive colors. And then there’s good, old-fashioned American advertising. Last Halloween season, Mars spent $9.4 million on marketing, followed closely by Hershey’s at $8.6 million.

But how these candies are so embedded in the American psyche in the first place actually has to do with a less obvious source: the United States military.

Related History Stories

World War II’s sugar shortage

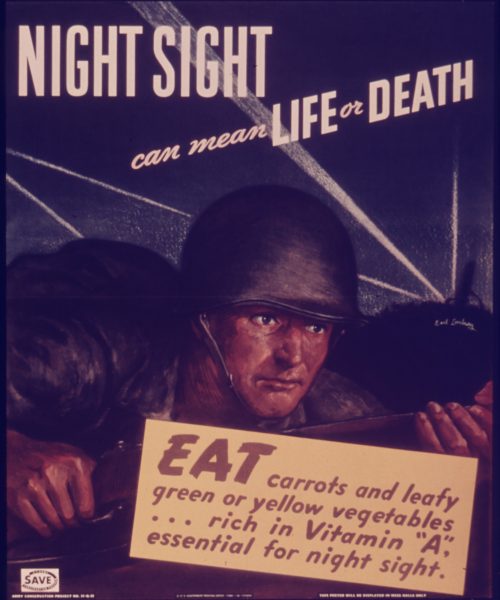

During World War II, sugar was scarce in the United States. Starting in April, 1941, it became the first food to be rationed. Many other items, such as women’s nylons and car tires, also joined the ration list to ensure the government could get the necessary raw materials for military vehicles, parachutes, and other gear. But the reason we ran low on sugar was a simple supply chain issue.

Before the war, much of the U.S.’s sugar came from the Philippines. But when Japan invaded the island nation in 1941, it cut off one of America’s key sugar suppliers. What’s more, many of the merchant cargo ships that would normally have transported sugarcane from Hawai’i, the nation’s largest domestic producer of the raw material, had been repurposed into military vessels.

“There was no way to get the sugarcane from Hawai’i to the processing plants in the United States,” says Elizabeth Aldrich, who writes about the period in Casseroles, Can Openers, and Jell-O: American Food and the Cold War, 1947–1959.

With sugar supplies so low, one might assume that American candy companies were an early casualty of war. Yet Hershey managed to keep doing a brisk chocolate business through the war—just not quite the way you might expect.

Introducing military-grade chocolate—the Ration D bar

By the time sugar rationing kicked into high gear, Hershey already had a contract with the United States military. In 1937, the government approached the candy-maker and asked them to make a calorically dense chocolate bar that could withstand high temperatures. Admittedly, these specimens were a far cry from anything you’d find in your Halloween mix. According to Sam Hinkle, Hershey’s chief chemist at the time, they were instructed to make bars that “taste a little better than a boiled potato.”

If that sounds like a low bar, that’s by design. The Ration D bar was for emergencies, which meant it couldn’t be too tasty, or troops would polish it off right away. The final product, made with oat flour, cocoa butter, sugar, chocolate, skim milk powder, and vitamin B1, was dense as a brick.

“They made this really horrible thing, which broke a soldier’s teeth and caused diarrhea and all sorts of bad stuff,” says Aldrich. The packaging advised crumbling the bar up and dropping it in boiling water to soften.

Nevertheless, the Ration D bars served their purpose. Just three of the bars packed in 1,800 calories, or roughly enough to meet the bare minimum for a day. Soldiers hauled them onto the beaches of Normandy on D-Day, along with their K Ration kits, which contained treats like coffee, cigarettes, and something closer to commercial chocolate—also made by Hershey, naturally.

America, home of the brave (and of chocolate)

Keeping spirits up among the American troops during World War II was indeed no mean feat. Casualties were high, conditions were dismal, and the finer points of geopolitical politics were lost on the twentysomething men drafted into conflict.

“One of the problems that the United States had was to convince its soldiers that they were fighting for a cause,” Aldrich says. “Most of these soldiers had never been to Europe before. The idea of the American way as a better way of life was the thing that pretty much kept a lot of these soldiers from losing their minds.”

Chocolate wasn’t a cause in and of itself, but what it represented was. All of these young men grew up under the Great Depression, when food was often a matter of survival rather than pleasure. The idea of America as a place of abundance, where there was chocolate and food for everyone, was a powerful one.

As sugar became harder to find during the second world war, “Mars and a couple of other candy companies went before Congress and they said, ‘Oh no, we really need to have these sugar shipments,” Aldrich says. “Hershey said, ‘We’re keeping the morale up for our soldier boys to remind them about the great American way and that they’re coming home to a better life.’”

US Soldier with Japanese Child Saipan 19

As Hershey continued production, chocolate bars found their way to American prisoners of war in care packages and to civilians in newly liberated towns and cities across Europe. During the Berlin Airlift, American pilots parachuted 23 tons of candy to the Germans below. One pilot, Gail S. Halvorsen, became so famous for dropping treats that he earned the nickname the “Berlin Candy Bomber” or “Der Schokoladen Flieger” (“The Chocolate Pilot”). Although he was initially acting outside orders, the military seized on the moment. The image of Americans bringing chocolate to the children of the world was forever etched in popular history.

Melts in Your Mouth, Not in Your Hand

Hershey wasn’t the only company to prosper during World War II. Mars supplied chewing gum to the troops, along with another candy still wildly popular to this day. In 1941, Forrest Mars Sr. received a patent for M&Ms, which were manufactured exclusively for the U.S. military. “They were commissioned by the U.S. government to come up with a candy that could be used in the tropics and the subtropics,” Aldrich says.

Mars had seen a similar candy with a durable sugar shell during the Spanish Civil War. He jumped on the idea as a way of creating an easy-to-transport sweet. “That’s where the whole idea of chocolate that melts in your mouth, not your hand comes from,” Aldrich says. The OG M&Ms were all plain chocolate, but they did come in a half-dozen different colors.

In 1947, the company started selling these many colored chocolates to the masses—and the rest is history. An entire post-war generation grew up with M&Ms, along with “The Great American Chocolate Bar,” as the Hershey’s bar was once called. Ever since, they’ve been a trick-or-treat stalwart, and this Halloween will undoubtedly be no different, as tiny spidermen and Elsas flood neighborhoods with pillowcases overflowing with M&Ms and Hershey’s bars.