While it may appear humble, Earth’s moss is built darn tough. It thrives in extreme environments–from the bitter cold, low-oxygen air of the Himalayas, down to the parched sands of Death Valley. Some species even make their home among the lava fields of active volcanoes. It can now add space to its list of homes.

In March 2022, a team from Hokkaido University in Japan sent several moss reproductive structures called sporophytes into space aboard the Cygnus NG-17 spacecraft. Over 80 percent of the spores survived for nine months outside of the International Space Station (ISS). The spores even returned to Earth still capable of reproducing. The findings are detailed in a study published today in the journal iScience.

“Most living organisms, including humans, cannot survive even briefly in the vacuum of space,” Tomomichi Fujita, a study co-author and biologist at Hokkaido University, said in a statement. “However, the moss spores retained their vitality after nine months of direct exposure. This provides striking evidence that the life that has evolved on Earth possesses, at the cellular level, intrinsic mechanisms to endure the conditions of space.”

Readying the moss

For Fujita, the idea for space moss struck while he was studying plant evolution and was interested in how the plant colonized Earth’s harshest environments. He began to wonder, “could this small yet remarkably robust plant also survive in space?”

To see, Fujita’s team turned to Physcomitrium patens, a well-studied species moss commonly called spreading earthmoss. They put the moss into a simulated space environment with high levels of ultraviolet (UV) radiation, extreme high and low temperatures, and vacuum conditions.

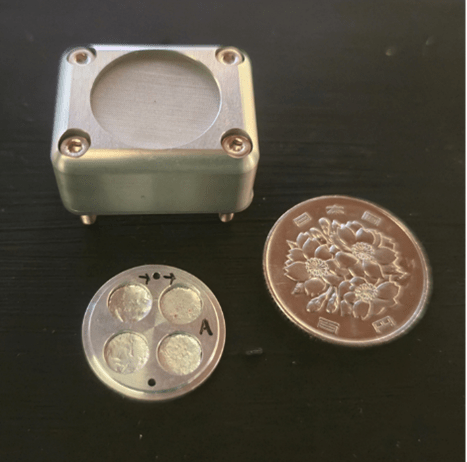

Next, the team tested three different structures from the moss–juvenile moss (called protenemata), the specialized stem cells that emerge under stressful conditions called brood cells, and the reproductive sporophytes that enclose the spores. Testing these three helped them determine which moss structure had the best chance of surviving in space.

“We anticipated that the combined stresses of space, including vacuum, cosmic radiation, extreme temperature fluctuations, and microgravity, would cause far greater damage than any single stress alone,” said Fujita.

The UV radiation proved to be the toughest element, but the sporophytes were the most resilient of the three moss parts. All of the juvenile moss died from the UV levels or extreme temperatures. While the brood cells had a higher survival rate than the juvenile moss, the sporophytes still exhibited about 1,000 times more tolerance to UV radiation. The spores could even survive and germinate after being exposed to temperatures of −320 degrees Fahrenheit for over one week, as well as after living in temperatures as high as 131 degrees for a month.

According to the team, the structure surrounding the spore appears to serve as a protective barrier. It absorbs UV radiation and physically and chemically covers the inner spore to prevent damage. This coating is likely an evolutionary adaptation that allowed the group of plants that moss belongs to (bryophytes) to transition from aquatic to terrestrial plants 500 million years ago. Moss has survived several mass extinction events ever since.

Moss goes to space

To put this huge evolutionary advantage to another test, the team sent the spores beyond the stratosphere and to the ISS. Once there, astronauts attached the sporophyte samples to the outside of the space station. The samples were then exposed to space for 283 days. In January 2023, the moss headed back to Earth on SpaceX CRS-16 and was returned to the lab for testing.

“We expected almost zero survival, but the result was the opposite: most of the spores survived,” said Fujita. “We were genuinely astonished by the extraordinary durability of these tiny plant cells.”

Over 80 percent of the spores survived their intergalactic journey. All but 11 percent of the remaining spores were able to germinate in the lab. The team also tested the chlorophyll levels of the spores. The levels were mostly normal except for a 20 percent reduction in chlorophyll a. Chlorophyll a is particularly sensitive to changes in visual light, which could explain why those levels dropped. Even with the reduced chlorophyll a, this change did not appear to impact the health of the spores.

“This study demonstrates the astonishing resilience of life that originated on Earth,” said Fujita.

How long could moss survive in space?

To see how much longer the spores could have survived, the team used the data from before and after the moss’s expedition to create a mathematical model. Based on this model, the spores could have survived for up to 15 years (or 5,600 days) under space conditions. However, they caution that this is just a rough estimate based on one experiment, and that a larger data set is necessary for more realistic predictions of how long moss could survive in space.

The team hopes that this moss experiment helps advance research on how extraterrestrial soils can plant growth and inspires more exploration of how mosses could develop agricultural systems in space.

“Ultimately, we hope this work opens a new frontier toward constructing ecosystems in extraterrestrial environments such as the Moon and Mars,” said Fujita. “I hope that our moss research will serve as a starting point.”