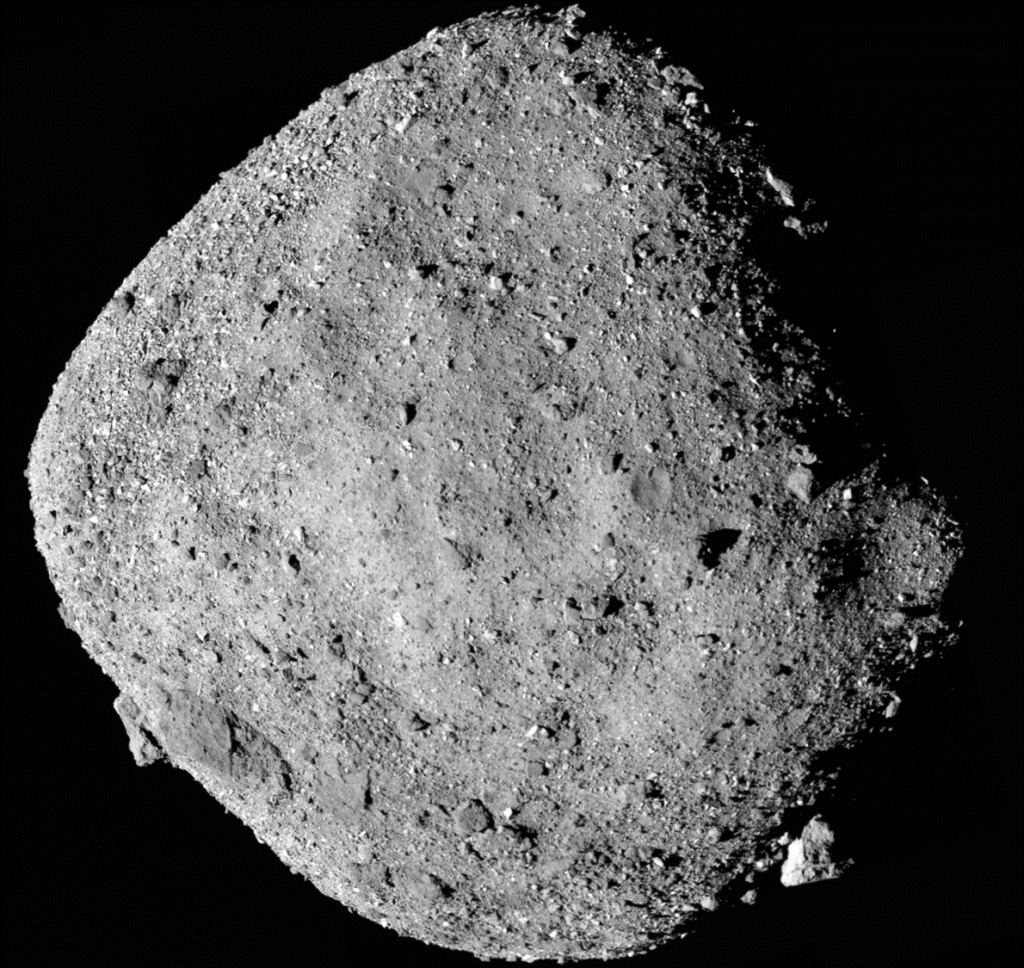

It took a while for scientists to gain access to the samples that NASA’s OSIRIS-REx mission took from the asteroid Bennu, but the wait is proving to be worth it. A new study published January 29 in Nature describes an unexpected discovery in the material delivered by OSIRIS-REx: residues of compounds left over by the evaporation of liquid water.

Tim McCoy, the paper’s lead author and the curator of meteorites at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, tells Popular Science that the presence of these compounds was completely unexpected. “[Finding them] was a complete surprise,” he says. “Collectively, the team that wrote this paper has hundreds of years of experience examining meteorites and none of us—in fact, nobody—had ever seen some of these minerals.”

One of the reasons that the discovery is so significant is that the compounds must have precipitated from the evaporation of brine solutions–solutions of liquid water with high concentrations of dissolved salts. “We know this,” McCoy explains, “both because some of these minerals … actually have water in their crystal structure, and because we know the most abundant fluid [in the universe] is water. There could have been a small component of other ices, like carbon dioxide, but it was mostly water.”

[ Related: This is what’s inside NASA’s previously stuck asteroid sampler ]

The presence of these compounds therefore implies the presence of liquid water at some point in Bennu’s history—or, more accurately, in the history of the ancient asteroid from which Bennu originated. That parent asteroid was a larger object that broke up into smaller pieces at some point during the last 65 million years. McCoy explains that the parent asteroid was formed partly of ice, and over the millennia, this ice was melted by heat from the decay of radioactive elements in the asteroid’s regolith.

McCoy says that this water “likely existed not on the surface, but as a vein or pocket under the surface of the asteroid.” This prolonged its existence in a liquid state, most likely, as McCoy says, at “about room temperature.” The dissolved minerals may also have allowed the solution to remain liquid for longer: brine solutions generally have lower freezing points than pure water. (This is why roads are salted during snowy weather.)

In any case, when the water did eventually evaporate, it left behind the concentrated precipitates that proved such a surprise to McCoy and his team—and when the parent asteroid broke up, those compounds were passed onto its successors, including Bennu. The first compound the team discovered in the Bennu sample was sodium carbonate, which had never been observed before in any other asteroid or meteorite. As it incorporates water into its crystal structure, its presence prompted McCoy and other teams around the world to search samples of other water-soluble compounds. They found 11 such compounds in total, all of which had been concentrated in a brine solution and then precipitated as the water evaporated.

This evidence for the presence of liquid water on the ancient body from which Bennu formed provides a tantalizing possibility: the possibility that Bennu’s progenitor may have seen the first stirrings of life. Brines of the sort that apparently formed in the pockets of liquid water on Bennu’s ancestor provide a favorable environment for the development of complex organic compounds. In a statement accompanying the release of the paper, McCoy said, “We now know from Bennu that the raw ingredients of life were combining in really interesting and complex ways on Bennu’s parent body.” The paper also speculates that similar brines may exist today in the interior of Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Mars’s moon Ceres.

Either way, McCoy says the apparent presence of liquid water in Bennu’s parent asteroid also tells us something important about that asteroid: “The fact Bennu’s parent asteroid incorporated ice means it had to form beyond the Solar System’s snow line.” This line marks the distance from a star at which the temperature falls below water’s freezing point. (In 2016, NASA captured an image of this phenomenon in a young solar system.)

The snow line is particularly important in the early days of a solar system, as the cloud of dust and gas that surrounds a nascent star begins to coalesce into the protoplanetary disk from which the system’s planets and other orbiting bodies will eventually form. Beyond the snow line, water is solid and aggregates readily into nascent planets and asteroids, whereas within the line, water remains gaseous and is harder to capture.

[ Related: 10 chaotic space-related mishaps of 2024 ]

This means that objects formed beyond the snow line are relatively rich in water, and one leading theory about the origin of the water on Earth is that it was acquired by the capture of such water-rich objects. And if those objects contained brine solutions rich in organic compounds, it’s at least theoretically possible that life may have already been evolving in those environments before their arrival on Earth.

Such theoretical possibilities aside, McCoy says the discovery of brine compounds shows the value of OSIRIS-REx having been able to take direct physical samples from Bennu. “These are incredibly rare minerals, so they can’t be detected from Earth.” In addition, he says, “Many of these minerals are unstable in the Earth’s atmosphere. Without the controlled return by a spacecraft mission and very careful curation in nitrogen to isolate them from the atmosphere, we would have never found [them] in the first place.”