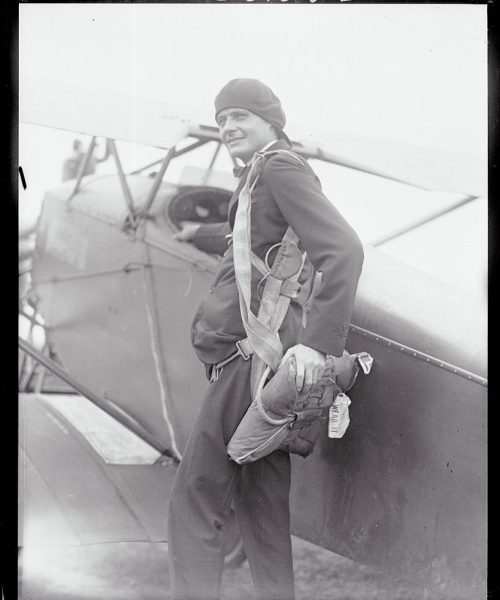

The serious son of Quaker parents, Philip Noel-Baker was first a scholar, then an Olympian, and finally a Nobel Peace Prize winner. He is the only person ever to have won both an Olympic medal and a Nobel.

First, an Olympic medal

By 1912, Noel-Baker had already earned honors in history and economics at Cambridge, and he was on the way to a graduate degree in international law.

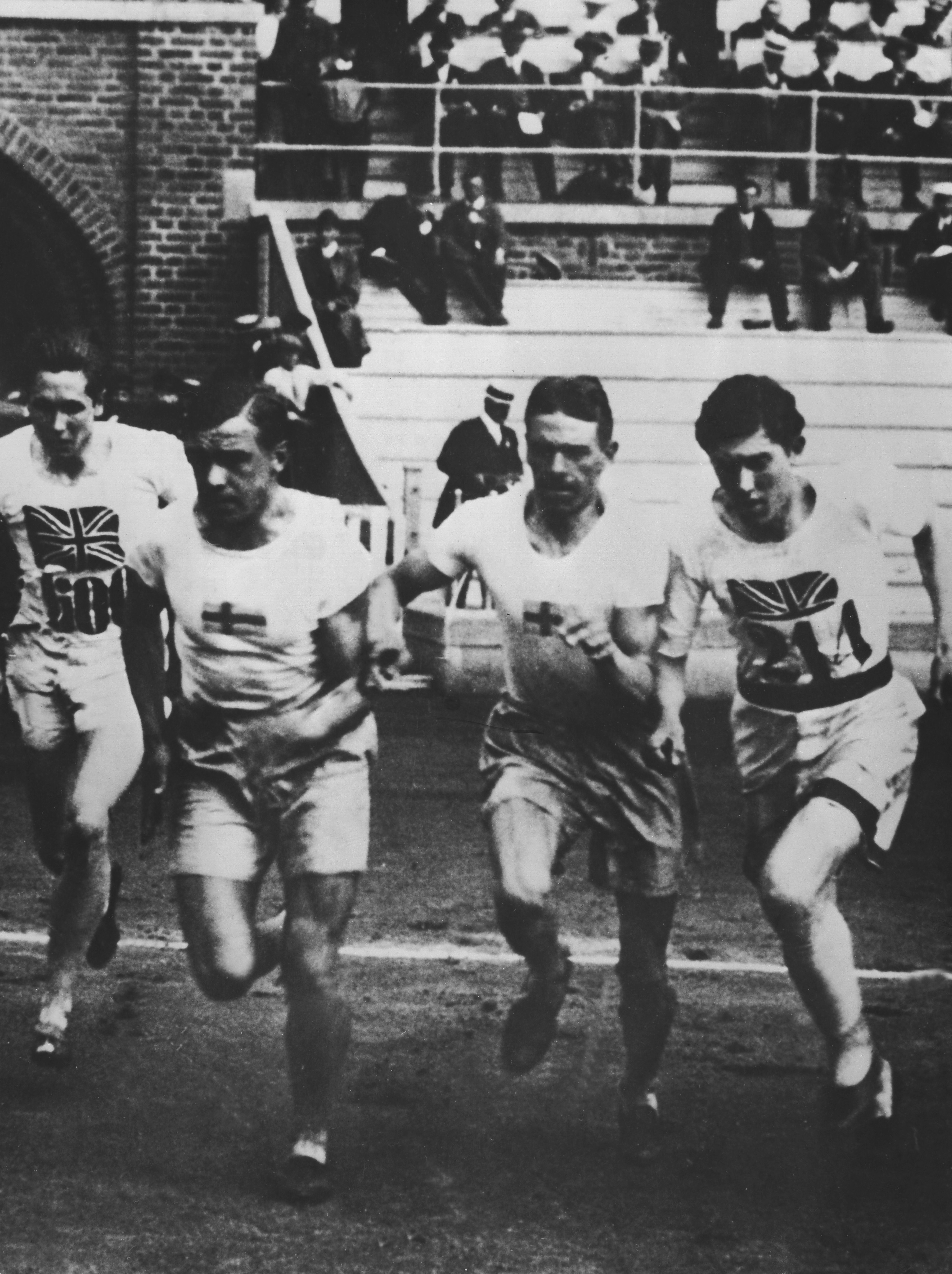

But the 22-year-old was also president of the Cambridge Athletic Club, and that July he took some time off from his studies to join the British track and field team for the fifth modern Olympic Games in Stockholm.

It was an eventful Olympiad. The American multi-sport phenom Jim Thorpe easily won the pentathlon and decathlon, prompting an impressed King Gustav V of Sweden to declare Thorpe “the greatest athlete in the world.” That year saw the Olympic debuts of equestrian sports, women’s aquatics, and the nation of Japan.

Great Britain took home a silver in tug-of-war, just one of 41 medals British athletes won that year. Noel-Baker was not among them; he ran the 800 and 1500-meter races, taking sixth place in the latter.

It may not have been his best showing, but Noel-Baker—who hyphenated his name when he married his wife, Irene Noel, in 1915—did better at the next Olympiad, held in Antwerp in 1920, after the 1916 Olympics were cancelled due to World War I.

That year, the 30-year-old won silver in the 1500 meter race, his only Olympic medal. But nearly four decades later Noel-Baker would return to Scandinavia for a gold one.

Then, a Nobel Peace Prize

Noel-Baker’s father, a successful London businessman and dedicated pacifist, put his own belief in public service into action as a member of the London County Council and, later, in the House of Commons. Noel-Baker took after his father, and was dismayed when war came to Europe so soon after the jubilant spectacle of internationalism he had witnessed in Stockholm.

On August 4, 1914, Noel-Baker “listened to Big Ben strike midnight as the Horse Artillery thundered along the Embankment to Victoria to entrain for France,” he later recalled. “And we knew that the guns were already firing, that the First World War had come.”

A conscientious objector, he would devote his own war effort to organizing ambulance services for Allied soldiers injured on the front lines, earning multiple citations for valor. But like many who had seen the worst of the so-called Great War, Noel-Baker returned with an even greater zeal for peace.

After the war, Noel-Baker served as principal assistant to Lord Robert Cecil, one of the architects of the League of Nations (and himself a future Nobel Laureate). He continued working for the League in various capacities throughout the 1920s and for most of the ‘30s, ‘40s, ‘50s and ’60s served in Parliament as a minister from the Labor Party.

After World War II, he joined the effort to replace the flawed League with what would become the United Nations, working tirelessly all the while for multilateral disarmament.

While some of his contemporaries advocated a realpolitik approach, or even hewed to the idea that powerful weapons were the best deterrent against violence, Noel-Baker “believed fervently in the cause of peace and advocated disarmament as the only answer to war,” said Professor Michael E. Cox, Emeritus Professor of International Relations at the London School of Economics, in a 2024 lecture. “In other words, he was not a realist. He was what many called him at the time, a romanticist—dare I even use the word—a utopian.”

Undeterred by Noel-Baker’s critics, the Norwegian Nobel Committee granted him the Peace Prize in 1959, shortly after the publication of his book, The Arms Race: A Programme for World Disarmament, which offered a detailed plan for getting rid of both nuclear and conventional weapons.

Philip Noel-Baker’s legacy

Eight more Olympics had taken place since Noel-Baker won his silver medal, the games interrupted by yet another world war. Meanwhile, new weapons had been developed, weapons more terrible than previous generations could have imagined. Noel-Baker, now nearing 70 years old, used his Nobel Lecture to look back on a dangerous half century, and to issue a warning to the future.

“The arms race still goes on; but now far more ferocious, far more costly, far more full of perils, than it was then,” he said. “It is the strangest paradox in history; every new weapon is produced for national defense; but all experts are agreed that the modern, mass-destruction, instantaneous delivery weapons have destroyed defense.”

Trying to curb war with rules and limits had come to nothing, he argued. Instead, he issued a challenge to the international community, the building of which had been his life’s work, from the track to the treaty table. Proudly utopian to the last, he declared, “I start with a forthright proposition: it makes no sense to talk about disarming unless you believe that war, all war, can be abolished.”

In That Time When, Popular Science tells the weirdest, surprising, and little-known stories that shaped science, engineering, and innovation.