Napoleon Bonaparte’s catastrophic invasion of the Russian Empire remains one of history’s greatest military blunders. In the summer of 1812, the French emperor set out across Eastern Europe’s Neman River with over 615,000 Grand Army troops intent on forcing their foe to agree to a continental blockade against the United Kingdom. In less than six months, over a half a million of Napoleon’s soldiers had succumbed to starvation, hypothermia, and disease.

The failed excursion is still studied today, with historical accounts suggesting typhus as a leading cause of death. However, recent microbial analysis conducted on the remains of Grand Army soldiers indicates at least two other pathogens played a central role in claiming thousands of lives. According to a study published today in the journal Current Biology, it wasn’t necessarily typhus that killed thousands of Napoleon’s men—it was a pair of nasty diseases known as enteric and relapsing fever.

It’s understandable why the typhus theory has remained popular for decades. Primary accounts from French doctors and soldiers cite the infectious disease possibly killing more troops than the Russians themselves. The discovery of typhus’ main vector–body lice–on bodily remains coupled with trace DNA of typhus’ bacterial cause (Rickettsia prowazekii) further supported this narrative.

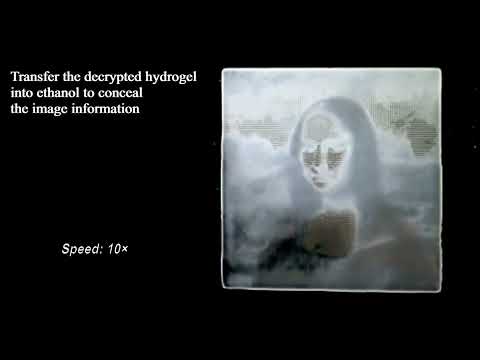

In recent years, technological advancements have opened the door to reexamining Grand Army casualties. It’s with this in mind that a team of microbial paleogenomicists led by Nicolás Rascovan at France’s Institut Pasteur decided to review the common narrative. To do this, they would need to examine the remains of some of Napoleonic excursion’s many victims. Their sources came from a mass grave located in Vilnius, Lithuania—a stop along the French army’s retreat in December 1812. After extracting and sequencing DNA from 13 soldiers’ teeth, they then cleaned their samples of any surrounding environmental contamination and searched for evidence of bacterial pathogens.

None of the men displayed any trace of typhus. Instead, the team discovered fragments of Salmonella enterica and Borrelia recurrentis. The former bacterium is responsible for enteric or typhoid fever, while the latter causes relapsing fever. Interestingly, both pathogens help explain the prior typhus theory. Typhoid fever’s name references its symptomatic similarities (“typhoid” means “resembling typhus,” after all), and wasn’t recognized as a distinct disease until later in the 19th century. Meanwhile, relapsing fever is often transmitted by body lice.

Rascovan’s team also discounted previous work that detected R. prowazekii or trench fever (Bartonella quintana) in soldiers buried in the same mass grave. They believe the reason for the earlier misidentifications likely came from the use of different sequencing technologies. Previous studies relied on polymerase chain reaction (PCR), a system that multiplies copies of a single DNA segment when source material is limited.

“Ancient DNA gets highly degraded into pieces that are too small for PCR to work,” Rascovan said in a statement. “Our method is able to cast a wider net and capture a greater range of DNA sources based on these very short ancient sequences.”

The study’s authors also made one more unexpected discovery. The strain of B. recurrentis seen on Napoleon’s soldiers is traceable to the same lineage other researchers recently discovered to have existed around 2,000 years earlier in Iron Age Britain. Although every present-day B. recurrentis strain sequenced so far has belonged to a different lineage entirely, the one identified by Rascovan’s team appears to have at least survived long enough to devastate the French army.

“It’s very exciting to use a technology we have today to detect and diagnose something that was buried for 200 years,” said Rascovan.