Popular depictions of schizophrenia often focus on visual hallucinations, but auditory hallucinations are far more common. At least 70% of people with schizophrenia experience hallucinations like “hearing voices,” and new research advances the theory that those voices are echoes of a person’s own speech.

To study this idea, researchers examined a mechanism the brain uses to distinguish between a person’s own voice and those of others—and found that this mechanism works differently in people with schizophrenia than in neurotypical people. They describe their findings in a new paper published October 3 in the journal PLoS Biology.

Your brain is constantly evaluating whether the sensory information it receives arises from your own actions or something that’s happening in your environment. This is an important distinction, because the appropriate reaction to that information may be very different: hearing a voice when there’s no one in the room is unsurprising if you’re talking to yourself, but startling if you’re not. Similarly, the way you experience that information might be very different: think about how it feels to, say, slap your own arm to try to kill a mosquito, and then how it’d feel if someone else suddenly slapped your arm unexpectedly.

Importantly, the brain can do this in cases where the distinction cannot be made from the sensory information alone. Speaking to Popular Science, Xing Tian—one of the paper’s co-authors—cites a common example of such a situation: tickling. “Most people,” he notes, “cannot tickle themselves.” And yet, whether it’s you or someone else doing the tickling, there’s no difference in what the nerves in your armpit communicate to the brain. The sensations they “feel” are the same.

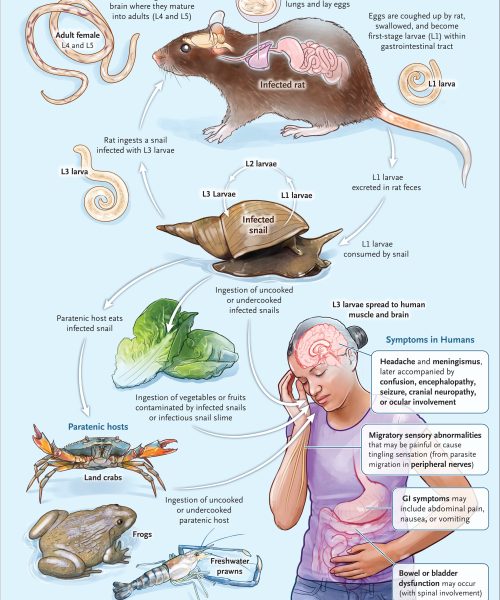

So how does the brain know the difference? Our best understanding is that when we are about to perform an action, the brain sends a message to our sensory organs, essentially telling them in advance what to expect: that your armpit is going to feel a tickling sensation, or your arm is going to feel a slap, or that your auditory nerves are going to hear a voice. As a result, some of the sensory responses you might otherwise experience—an uncontrollable urge to giggle, a sense of shock and pain at someone slapping you, or the surprise of hearing someone’s voice unexpectedly—are suppressed.

The key point here is that it appears this system does not work correctly when people with schizophrenia hear themselves speak. In other words, Tian says, “[People with schizophrenia] cannot suppress their echo of their own voices.”

Of course, people with schizophrenia don’t just hear auditory hallucinations when they’re preparing to speak, and one of the questions that the paper addresses is how the apparent malfunction of the suppression mechanism generates the more general phenomenon of hallucinations. “A suppressive function cannot really provide the foundation of a positive symptom,” Tian agrees. He and his team thus “tested [the hypothesis that] differential impairments in … two functional signals are the cause of auditory hallucinations.”

These two signals—the “corollary discharge” and the “efference copy”—combine to make up the “message” discussed above. Tian explains that the former “inhibit[s] neural responses to self induced sensory feedback” telling the senses to suppress some of their responses to an action. The latter, meanwhile, is a copy of the information sent to whichever parts of our motor system will carry out the action in question. This tells the senses what to expect. As Tian explains, “The perceptual feelings can be estimated based on the efference copy.”

Historically, these terms have been used somewhat interchangeably, reflecting the fact that the idea of advance signaling was proposed independently by two different researchers. One key insight of Tian and his colleagues’ research is that “based on the positive nature of the auditory hallucination symptoms—patients can generate perceptual feelings of hearing something [without] external sounds to induce the perception—there must be two different functional signals, one for generating the perceptual feelings [the efference copy] and one for labeling the sources where these feelings come from [the corollary discharge].”

In people with schizophrenia, neither signal appears to work properly. The corollary discharge’s labeling function is unreliable, resulting in a reduced distinction between their own speech and that of others. Meanwhile, the efference copy sent to the auditory system is also imperfect, so the auditory system is given incorrect information about what it should expect to hear.

The result is a sort of feedback loop: in someone with schizophrenia, the brain is less able to distinguish between the person’s own voice and that of others, and also prone to accidentally treating the latter as the former. As the paper says, “The positive symptoms of audiovisual hallucinations are an emergent property of … a ‘broken’ CD misattributing the inducing sources of … auditory neural representations that are activated by a ‘noisy’ EC without external stimulations.”

Tian suggests that this research may go some way to explaining why auditory hallucinations are more prevalent in people with schizophrenia than other forms of hallucination. Speaking is a far more active process than seeing, and as a result, also more vulnerable to any imperfections in the way we experience our own actions.

“There is a tight relation between the action and its consequence in the auditory domain,” he explains, “[more so] than that in the visual domain. The differences highlight the fundamental differences between the visual and auditory domains as well as their relationship to the motor system. [In speech], such a tight causal relationship necessitates shaping our neural system via extensive experience, and possibly establishing special and strong neural connections between motor and auditory systems.”

More broadly, the paper provides strong evidence that the way in which our motor system functions (or malfunctions) can affect the way we experience the world. Tian says that this points the way to possible treatments for schizophrenia, along with the potential for future research into whether other mental illnesses might also have symptoms whose causes can be found in sensory input.

“Our findings indicate that the motor and auditory systems are likely working together,” he says, “so targeting these nodes in the network—for example, using non-invasive neural modulation methods—could [provide] potential treatments and intervention strategies for alleviating auditory hallucinations. And if our theory about how the motor system and action play a broader role in human cognition is [correct], we can extend our research program.” He cites “depression, anxiety [and] autism” as potential areas for future research.