On July Fourth, amid a cacophony of fireworks and flame-throwing propane grills, a seemingly ordinary lightning strike hit somewhere in Grand Canyon National Park. The resulting spark ignited surrounding dry vegetation, and strong winds quickly spread the flames for miles. Over the course of several weeks, that initial spark has grown into a blaze engulfing more than 100,000 acres, officially classifying it as a “megafire” and the largest wildfire of 2025…so far. As of this writing, “The Dragon Bravo Fire” has already destroyed 70 buildings, including the historic Grand Canyon Lodge.

It’s impossible to completely prevent wildfires like this one, but one of the most effective mitigation strategies is also one of the oldest. For centuries, firefighters around the world have used controlled burns, sometimes called a prescribed fire, to preemptively remove leaves, dead branches, and other dry materials that can serve as combustible fuel in the path of raging wildfires. Removing that fuel, the idea goes, should help prevent a wildfire from getting even larger and more dangerous.

Increasingly though, these controlled burns aren’t being initiated by people on the ground or from piloted aircraft overhead, but by small quadcopter drones carrying hundreds of ping pong ball-sized “Dragon Eggs.” These combustible eggs ignite small, trackable and contained fires when they are released.

Drone Amplified, a Nebraska-based startup, pioneered this system, which it calls “IGNIS” in 2017 with input from the U.S. Department of the Interior and the U.S. Forest Service. Now, eight years later, Drone Amplified’s Vice President of Business Development Dan Justa tells Popular Science that the company’s drones are currently operating more than 200 systems in at least 30 US states, as well as Canada, Germany, and Australia.

“This [system] allows you to cover a tremendous amount of ground and get eyes on fire for situational awareness during wildfires,” Justa said. “It also allows you to fly at night.”

Moving from recon to intervention

Firefighters have been using drones in some capacity for well over a decade. Around 2011, state and federal agencies began deploying drones equipped with cameras to capture photos and videos—either for early surveillance or to assess damage after a wildfire. From the beginning, small, unmanned drones were viewed as more affordable alternatives to helicopters for wildlife monitoring and real-time data collection. Their compact size also lets them access areas that may be unreachable by larger, piloted aircraft.

The Western Fire Chiefs Association estimates that around 200 fire departments across the U.S. were using drones by 2018. That number tripled within just two years. Drone Amplified represents a more recent shift toward using those drones for active wildfire mitigation, moving a step beyond basic surveillance and documentation. Drone companies focused on disaster response also gained momentum following the passage of a bipartisan 2019 bill that encouraged greater drone use by federal agencies in wildfire management operations.

“One of our North Stars is doing cool stuff with drones that actually impacts the world rather than just images,” Justa said. “A lot of drones are just flying cameras or sensors.”

Fighting fire with fire

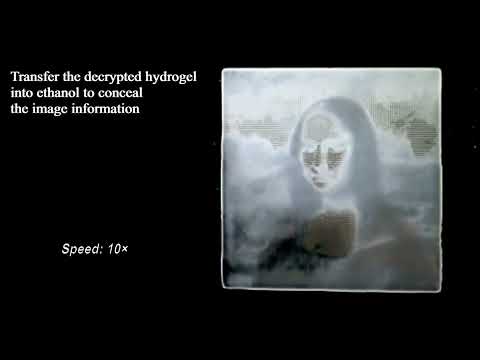

Drone Amplified’s IGNIS system, which gestated from research done by a pair of professors at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, consists of four main subsystems. According to Justa, the drone itself is a heavily modified version of the American-made Freefly Systems Alta X model. Attached is a large hopper that holds up to 450 (or around 13 pounds) of the “Dragon Egg” balls. These small plastic spheres are filled with potassium permanganate. During a controlled burn, each ball is dropped into a separate puncture mechanism where it’s injected with ethylene glycol, a compound commonly found in antifreeze. The resulting chemical reaction produces a steady, relatively cool, and controlled flame.

Once pierced, the Dragon Eggs take about 30 to 45 seconds to ignite, during which time they are launched from the drone toward their pre-programmed targets. This process can be repeated up to 120 times per minute until the hopper is empty. Firefighters can adjust the number of eggs dropped depending on the desired intensity of the burn. Each payload is also programmed to release the incendiary balls only within a specific geographic area.

Firefighters control the drone using a companion app. The drone is equipped with thermal cameras, allowing operators to see targets clearly even in smoky conditions and to monitor the progress of prescribed burns once they begin. According to Justa, the drone, its accompanying software, and the necessary training combined cost approximately $100,000.

That sounds like a lot of money, but it’s often a more affordable option than deploying a helicopter with a full crew of firefighters. It’s also notably safer. Drones aren’t affected by smoke inhalation or the risk of carbon monoxide poisoning, allowing them to operate in more hazardous environments. There’s the added benefit too that crashing a drone, while pricey, isn’t life threatening. The CDC estimates around 25 percent of all firefighting fatalities are related to aviation.

“It’s extremely dangerous to fly helicopters over wildfires because you have thermals, you have smoke, you can’t see anything,” Justa said. “The drones you can put up anywhere.”

All of this gives firefighters equipped with drones greater capacity and flexibility to carry out prescribed burns, tools that can make a significant difference. A 2024 study published in the Forest Ecology and Management found that prescribed burning, when combined with tree thinning, reduced wildfire severity by more than 60 percent compared to areas that did not receive similar treatment.

Making sure Dragon Eggs are used for good

But there’s also the concern of ensuring that a drone capable of starting a wildfire does so only in the place it’s supposed to. To that end, Justa says the company has designed its system with safety and mitigation tools built in from the ground up. While pilots are free to navigate the drone as needed, the hopper will only dispense the Dragon Eggs within a predetermined, geofenced area—the designated controlled burn zone. Sensors onboard can detect if the drone or its payload sustain damage. If that happens, the system automatically disables the dropper mechanism and triggers a small, low-temperature fire designed to safely burn out.

And as for the risk of hackers gaining access to the device and using it to wreak havoc, Justa says the drones mitigate risk by using radio-based encryption. He also points out that anyone intent on starting a forest fire almost certainly has easier methods available to them. Buying a pack of cigarettes at a gas station is far cheaper and simpler than hacking a drone.

Though its most notable impacts so far have been in wildfire management, Drone Amplified’s object-dropping mechanism isn’t limited to dispensing Dragon Eggs. Last month, the company partnered with the American Bird Conservancy to drop dozens of biodegradable, lab-grown mosquito pods over Hawaiian forests in an effort to curb the area’s invasive mosquito population, which poses a serious threat to some native bird species. Justa told Popular Science that the company is also working with the Alaska Department of Transportation to deploy controlled explosive charges for triggering managed avalanches.