During the decades that humanity has collectively been exploring space we’ve sent up a lot of stuff. Much of it has stayed up there, orbiting the planet or eventually falling back to Earth and burning up in the atmosphere (or sometimes not).

To really send something far out into space, though, you’ve got to put more effort in. Rocket-fueled effort. The spacecraft that’s been launched to explore the outer reaches of the solar system needed a boost to get there, and then further help from the gravity of the planets they passed. Thanks to the general lack of friction in space combined with the abundance of open space, these projectiles can just keep going. The man-made object that is farthest away from Earth and will continue to hold the title is the Voyager 1 spacecraft, followed by Voyager 2.

Voyager 1 was launched a couple weeks after Voyager 2, both in 1977. Voyager 1 was so named because it was on a faster trajectory to reach Jupiter and thus would be the first Voyager to see that planet. It is currently more than 15 billion miles away from Earth. Voyager 2 is more than 12 billion miles from home.

The probes will celebrate 47 years of operation this year and are NASA’s longest operating spacecraft. Both Voyager probes have flown past Jupiter and Saturn. Voyager 2 has also flown past Uranus and Neptune.

[Related: Carl Sagan in 1986: ‘Voyager has become a new kind of intelligent being—part robot, part human’]

These are the only two spacecraft, according to NASA, to “directly sample interstellar space.” Interstellar space is the region outside the heliosphere–the protective bubble created by solar winds. That protective bubble drops off when the force of the solar winds is counteracted by interstellar winds. Voyager 1 and 2 both left the heliosphere and are now in interstellar space. Technically, both are still within the solar system, and will be for a while. The probes will have left the solar system when they pass beyond the Oort Cloud. Voyager 1 will reach the leading edge of the Oort Cloud in roughly 300 years.

Engineers are still sending commands to Voyager 1 and receiving usable information from the spacecraft. Because of the vast distance it’s traveled, NASA says it takes more than 22 and 1/2 hours for light from Earth to reach the spacecraft and the same amount for signals from Voyager 1 to return to Earth. When engineers send a command to Voyager 1 they need to wait two days to find out if it worked.

In May of 2024, Voyager 1 resumed sending scientific data from two of its four instruments after a computer issue took the instrumentation out of commission in November 2023. In June of 2024 Voyager 1 was back to conducting normal scientific operation with all four instruments after troubleshooting efforts by NASA. The four instruments study “plasma waves, magnetic fields, and particles,” according to NASA’s description of the probe.

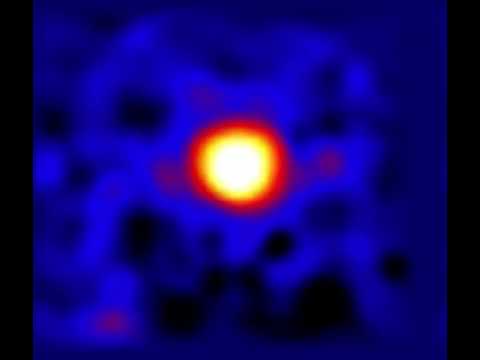

Voyager 1 was responsible for one of the most iconic space photos in the history of the space program. In 1990, while still at a relatively close 3.7 billion miles away from Earth, the space probe took the image now immortalized as the “pale blue dot.”

A small pinprick of light–Earth, only a pixel in size–hangs as if suspended in a ray of sunshine. The image was composed from a series of 60 images taken by Voyager as it passed beyond Neptune. Team managers instructed the probe to look backwards toward home and take a final series of images. According to NASA, Voyager 1 is one of only three spacecraft that could ever have taken such an image (Voyager 2 and New Horizons are the others). Also captured in the Solar System Family Portrait were Neptune, Uranus, Saturn, Jupiter, and Venus.

The images that formed the basis for the iconic photo were taken barely half an hour before the probe’s cameras were permanently shut down in February 1990. It wasn’t until May of that same year, that all of the file data was received back on Earth and could be processed.

Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 continue on their outward trajectories, slowly losing power and capabilities until they’re truly shut down and out of range. Scientific data may be sent back to Earth for several more years after the crafts’ instruments have shut down, depending on how much power is available.

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.