An international team of scientists believe they have finally found the elusive answer to the question of why moths are drawn to light. The artificial light appears to trap moths and other flying insects in a wonky flight pattern. The light makes them lose their sense of up and down, since they are used to following light in the night sky instead of on the ground. The moths aren’t necessarily attracted to the light, but are more likely trapped in its glow. The findings are described in a study published January 30 in the journal Nature Connections.

[Related: Light pollution is messing with coral reproduction.]

Millions of years of evolution

Moths and butterflies have called Earth home for at least 200 million years. Through that time,

moths and other insects that fly at night may have evolved to tilt their heads back towards whatever direction is brightest. This light source was originally the stars and moonlight in the sky and not on the ground. This ensured that the bugs knew which way was up and kept them flying level.

When artificial light sources began to fill up the Earth, the moths found themselves tilting their backs at lamps in the street or fires. This caused them to fly in endless loops around the streetlamp, as they were trapped by instincts learned through millions of years of evolution.

“This has been a prehistorical question. In the earliest writings, people were noticing this around fire,” study co-author and Florida International University biologist Jamie Theobald said in a statement. “It turns out all our speculations about why it happens have been wrong, so this is definitely the coolest project I’ve been part of.”

Monitoring flight paths

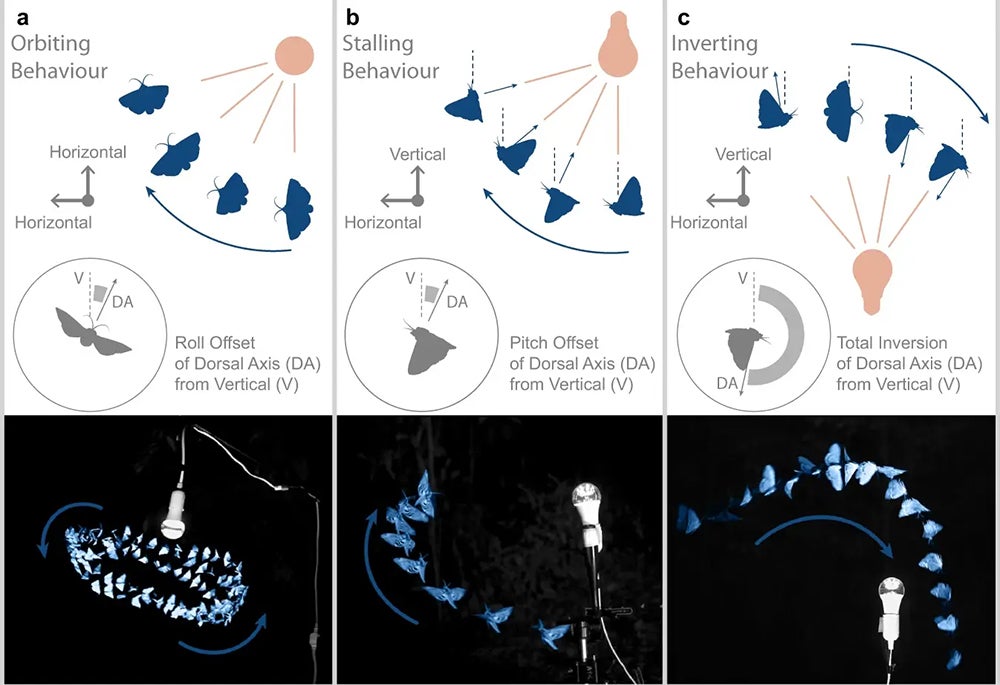

In the study, a team of international researchers in the Costa Rican cloud forest used high resolution and high-speed infrared video recordings to capture insect flight paths around artificial lights. They collected over 477 videos spanning more than 11 insect orders. This technology was able to capture the insects’ fast and frenzied orbits by the lights and was used to reconstruct points of their flight paths in three dimensions. The team noticed that moths and dragonflies turned their backs to artificial lights, which appeared to drastically change their flight paths. The insects may have thought that the lights were a source of light in the sky and not on the ground.

“If the light’s above them, they might start orbiting it, but if it’s behind them, they start tilting backwards and that can cause them to climb up and up until they stall,” study co-author and Imperial College London entomologist Sam Fabian told The Guardian. “More dramatic is when they fly directly over a light. They flip themselves upside down and that can lead to crashes. It really suggests that the moth is confused as to which way is up.”

The research has some entomologists buzzing, since it provides a potential answer to a phenomenon in nature that is millions of years old.

Conservation concerns

This study is the first known documentation of this behavior in nocturnal insects and provides a new possible explanation of why lights seem to attract moths. While it appears to confirm that light is disruptive, it also gives new insights into a conservation concern. Light pollution is a major reason behind recent declines in insect populations. Moths and other insects can become trapped in the lights and become easy prey for bats. The fake light can also make moths believe that it is daytime and signal that it is time to sleep and not eat.

[Related: City lights could trigger a baby boom for some moths and butterflies.]

The study also suggests light direction matters when designing and installing exterior lights. According to the team, the worst direction is an upward facing or bare bulb. Shrouding or shielding a lightbulb could help offset the negative impacts.

Scientists are also beginning to think about how light color impacts flying nocturnal insects. The unexplained mystery of how these insects are initially attracted to light over great distances also still remains.

“I’d been told before you can’t ask why questions like this one, that there was no point,” Yash Sondhi, a postdoctoral researcher at the Florida Museum of Natural History and study co-author, said in a statement. “But in being persistent and finding the right people, we came up with an answer none of us really thought of, but that’s so important to increasing awareness about how light impacts insect populations and informing changes that can help them out.”