Beneath a darkening sky, the stars are just beginning to freckle through the canopy of a thick forest. Smoke unfurls upward from the crackles of a campfire, as the scent of charred pine and sizzling onions fills the air. Perhaps you’ve just hiked 10 miles, your feet ache, and your fingers are wrapped around a warm bowl of stew cooked over open flame. And though the ingredients are simple and the tools primitive, it might just be the best food you’ve ever tasted.

But why does food taste better by a campfire? The answer, it turns out, has less to do with the food itself and more to do with the multisensory symphony surrounding it. It’s chemistry, psychology, evolution, nostalgia, joy, and the ancient pull of that warm glow that has gathered us for millennia beneath the stars.

[ Related: How to build and extinguish a campfire without sparking a catastrophe. ]

A multisensory illusion

“When you’re around a fire, you’re kind of in the pot,” says evolutionary biologist Robert Dunn, author of Delicious: The Evolution of Flavor and How It Made Us Human. “You’re fully experiencing the results of the cooking and of the eating.”

Flavor, Dunn notes, is not just a matter of taste buds. It’s an intricate interplay of smell, texture, temperature, sound, memory, and even narrative. A key player in this process is retronasal olfaction—the aroma of food drifting from the back of your mouth up into your nasal cavity. Around a campfire, you’re not just tasting the food; you’re breathing in a full cloud of aromatic particles, both from the dish and the fire itself.

“You’re getting, in essence, a double dose,” Dunn says. “The flavor includes the smells that are in your mouth and around the fire.”

Fire makes food chemistry magic

When food is grilled, roasted, or scorched over a fire, it undergoes the Maillard reaction, a chemical process where amino acids and sugars recombine to create hundreds of complex flavor compounds. It’s what gives seared steak, toasted marshmallows, and golden-brown bread their irresistible taste.

On top of that, fire introduces pyrolysis—the thermal breakdown of organic materials—which adds smoky, sometimes bitter-edged notes. Unlike stove top convection, fire cooking relies heavily on radiant heat and smoke infusion. Tiny aerosolized particles carry flavor compounds from the burning wood directly into the food. Researchers have identified dozens of aromatic molecules—like guaiacol and syringol—in wood smoke that enhance the perception of umami and sweetness.

Renowned food science writer Harold McGeehas argued that we may be biologically attuned to the complex aromas of meat cooking. “If that’s true,” Dunn muses, “what if we’re innately tuned to complex experiences too?”

Why nature heightens flavor

Beyond food, the campfire experience is about place, body, and mind. Environmental psychology offers a few clues. Studies have shown that spending time in nature lowers cortisol (a stress hormone), sharpens attention, and boosts sensory sensitivity. In this more attuned state, we quite literally taste more.

There’s also the effort justification effect—a principle from behavioral psychology that says we tend to value outcomes more when we’ve worked for them. That trail-cooked chili might taste divine partly because you foraged for kindling, stirred the pot, or simply earned it through sweat and blistered heels.

And, firelight itself, like warm-toned lamps or a candle glow, have been shown to relax the brain and to likely increase oxytocin, the so-called “bonding hormone.”

“In the isolated world we live in today, around a fire you’re with other people,” Dunn says, “and you get a hormonal bump—like chimps grooming each other.”

[ Related: Ice age humans built sophisticated fireplaces. ]

A ritual older than us

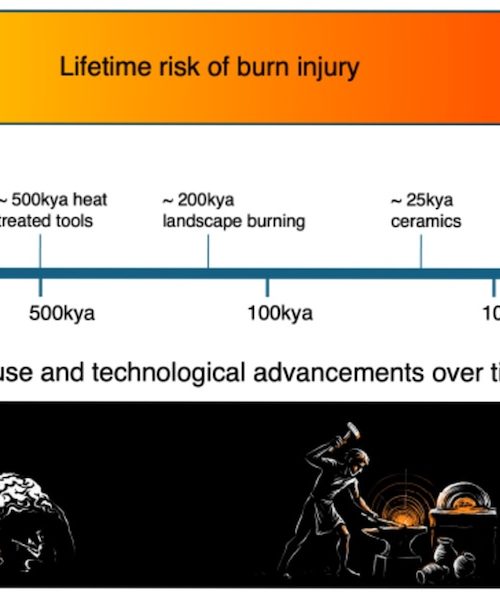

Cooking over fire is also one of the oldest things humans do. Anthropologists estimate that our ancestors began using fire to prepare food over a million years ago, long before we were even fully human. Fire not only made our food safer and more digestible, it transformed meals into communal experiences.

“You’re reconnecting with a way of being with other people that’s our most ancient way of being,” Dunn continues. “That’s a deeper satisfaction. “What’s the benefit of being able to see the stars? It’s more than anything that the word ‘flavor’ is going to capture.”

Indeed, around a fire, we fall into rhythm. Someone stirs, another tells a story, others peer up into the cosmos. The act of cooking and eating becomes a ceremony, and flavor becomes inseparable from presence. For many, the taste of charred marshmallows or hot dogs evokes childhood summers, bonfire songs, or family togetherness—memories stored not just in the brain’s hippocampus but in the gut, the skin, and the smoke-clung hair.

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.