Robert F. Kennedy Jr., the recently appointed secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), has long promoted unfounded conspiracy theories regarding community water fluoridation. Now that he’s settled into his new role in President Trump’s cabinet, RFK Jr. is positioned to act on those views. On Monday, RFK Jr. affirmed that he plans to direct the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to stop recommending water fluoridation nationwide. In collaboration with Kennedy, Lee Zeldin–head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)–announced that the EPA would work rapidly to develop new guidelines for the maximum allowed levels of fluoride in drinking water. Along with life-saving vaccines, community water fluoridation is in the crosshairs of the “Make America Healthy Again” movement.

At the same time, states are making their own quick decisions. Last month, Utah became the first U.S. state to ban community water fluoridation. For decades, municipalities in the state have chosen whether or not to add a small amount of fluoride into the public water supply, in accordance with EPA regulations and federal guidelines. About 44 percent of Utahans received fluoridated water through their taps under that status quo. But beginning May 7, when the new law takes effect, that prior level of local control won’t be allowed and that percentage will be legally mandated to fall to zero. Similar bills have been introduced in a handful of other states, including North Dakota and Montana.

Fluoridation has well established benefits for oral health–reducing the risk and rate of tooth decay, cavities, and even childhood dental surgeries. Decades of public health studies suggest the practice is safe. At the same time, research into the potential effects of high levels of fluoride exposure (more than double or quadruple the amount used in community fluoridation programs) on childhood cognitive development have prompted renewed concerns and questions. Some scientists and health experts disagree about how to consider fluoride’s known merits versus possible risks. Here’s how to understand this nuanced public health issue.

Why fluoridate?

Water fluoridation is a public health intervention with the goal of preventing tooth decay and cavities. Fluoride is a mineral that helps strengthen developing tooth enamel in children and aid in the remineralization of adult teeth–both preventing and reversing damage and decay.

“The nice thing about water fluoridation is that everybody benefits, not just the people that have health insurance or a high income–everybody. Young children, but also seniors, adults, and individuals with disabilities.” says Jennifer Meyer, a registered nurse and assistant professor of public health at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

[ Related: To rinse or not to rinse? You might be brushing your teeth wrong. ]

Many sources of drinking water, including private wells, naturally contain some amount of fluoride. But community water fluoridation is done with the intent of optimizing fluoride concentration for the dental benefits. In the United States, about 72 percent of people have access to fluoridated tap water. Municipalities in many other countries, including Ireland, Australia, and Canada also fluoridate their public drinking water. In addition to water, there are other fluoride exposure sources, including toothpaste, dental varnishes, and certain foods and beverages that are naturally high in the mineral like black tea, coffee, and shellfish.

Assuming levels don’t veer too high (which they rarely do in the U.S.), the benefits of fluoride are additive, says Scott Tomar, a professor and associate dean of public health dentistry at the University of Illinois Chicago. Even if a person brushes their teeth with fluoridated toothpaste and regularly goes to the dentist, drinking fluoridated tap water still offers a protective bonus, Tomar explains, counter to Utah Governor Spencer Cox’s claim that fluoridation is ineffectual.

For those with limited access to dental care, fluoridated water makes an additionally significant difference. One 2018 study in the Journal of Dental Research assessing the impacts of water fluoridation in the U.S. found that, children in fluoridated counties incurred 1.3 fewer cavities per person, on average, than their counterparts in unfluoridated counties. Among poorer communities, that difference is magnified to more than two fewer cavities per child with fluoridation. Additional regional research has found similar effects. In Windsor, Ontario, the city council voted to end water fluoridation in 2013, only to reverse that decision five years later after the percentage of children with tooth decay or in need of urgent dental care increased by 51 percent.

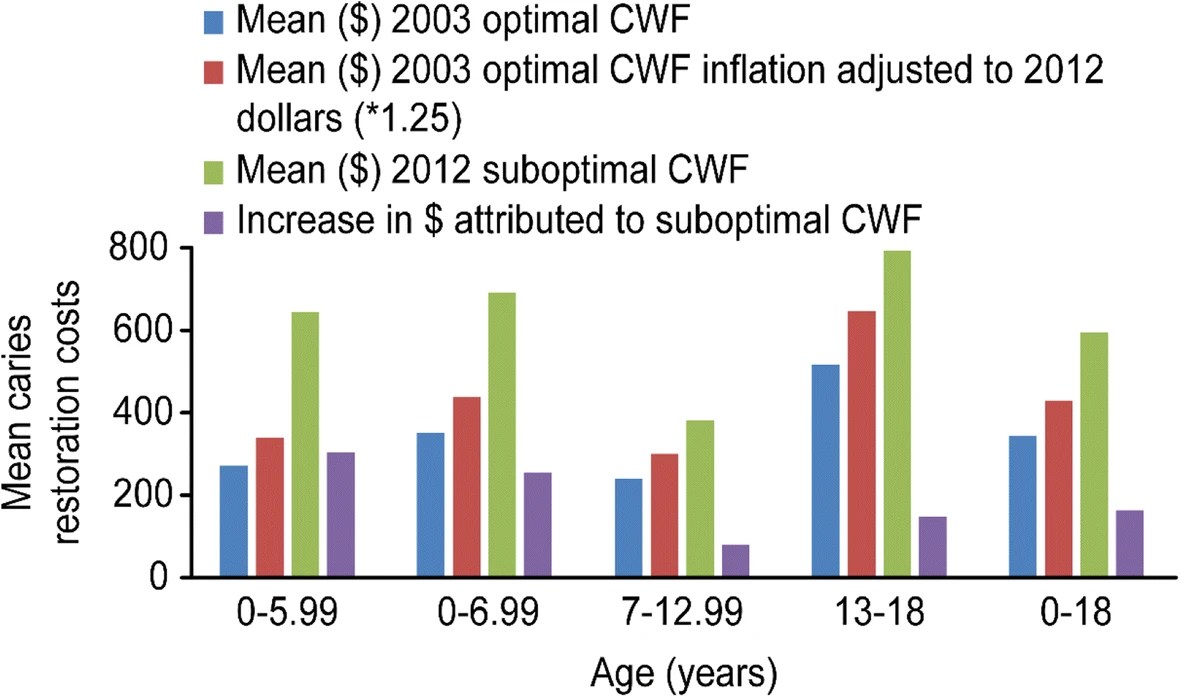

One study of Medicaid claims in New York State found that the number of claims for dental procedures related to cavities were 33.4 percent higher in less fluoridated counties, indicating many more instances of tooth decay. The cessation of water fluoridation in Juneau, Alaska led to $161 of average additional Medicaid cost for each child 0 to 18 years old, according to a 2019 study co-authored by Meyer. For young children, between 0 and 6 years, the added cost in the absence of fluoridation was more than $300 dollars. Those added Medicaid costs are subsequently borne by state and federal taxpayers. “Withholding water fluoridation from communities [imposes] a hidden healthcare tax on families,” says Meyer.

In Utah, with the end of water fluoridation, “I expect that we will see an increased rate of tooth decay, starting first with the youngest children,” says Tomar. He also expects the costs of oral upkeep and healthcare to rise for families and for the state. Every dollar spent on community fluoridation programs saves about $20 in turn, according to a 2016 estimate Tomar co-authored.

And cavities aren’t just minor annoyances or financial impositions, they’re the most common chronic childhood disease in the U.S., according to the CDC. They can have a serious impact on quality of life, negatively affecting things like school attendance and performance. Left untreated, cavities can raise the risk of malnourishment, lower self esteem, and lead to abscess and more serious infections. Globally tooth decay is the most common health condition, according to the World Health Organization.

But is water fluoridation dangerous?

Despite the proven plusses for oral health, community water fluoridation has faced opposition since its inception–when Grand Rapids, Michigan became the first U.S. city to fluoridate its tap water in 1945. The critiques are based on everything from false fringe beliefs to actual scientific studies.

Unsubstantiated conspiracist claims that fluoridation is a communist plot or a form of government mind control have abounded since the mid-20th century. Many people are opposed to fluoridation because they see it as a violation of their personal freedoms or a form of government overreach.

Then there are the waves of more scientifically-rooted health worries. For instance, concerns emerged in the 1990s based on rodent studies that fluoride exposure could increase the risk of bone cancer. That proposed association has since been largely disproven.

There is well-established health research indicating that too much fluoride can cause health problems. As with anything we ingest, the amount is critically important. Even essential nutrients like vitamin D and vitamin A can become toxic past a certain level of exposure. The EPA currently recommends that drinking water contain below 2.0 milligrams of fluoride per liter. The agency also mandates fluoride levels below 4.0 mg/L because of the risk of skeletal fluorosis, in which chronic, high levels of fluoride exposure can cause developing bones to grow weaker. The current U.S. federal guideline suggests optimal water fluoridation level is 0.7 milligrams per liter, which was most recently adjusted down from a range of 0.7-1.2 mg/L in 2015 to minimize the risk of tooth staining.

Too much fluoride and child cognitive development

However, the latest focus of fluoridation concerns is not bone disease or tooth staining, but childhood cognitive development. This is where things become murky and unsettled. Some scientific research–including a divisive review study published in JAMA Pediatrics in January and a related report from the National Toxicology Program–suggests an association between high amounts of fluoride exposure and population-level decreases in children’s IQ levels.

The review assessed 74 total studies, and concluded that exposure to fluoride levels above 1.5 mg/L in utero or infancy is associated with a dose-dependent reduction in childhood IQ of a few points.

“We found that IQ’s of children were inversely associated with the estimated fluoride exposure to those children during pregnancy and early childhood,” John Bucher, review co-author and an environmental toxicologist and former associate director of the National Toxicology Program, tells Popular Science.

Critically, Bucher and his co-researchers found no significant association between levels of fluoride exposure below 1.5 mg/L in drinking water and IQ losses, and write that more research is needed to understand what, if any impacts, occur at the recommended 0.7 mg/L community water fluoridation level in the U.S..

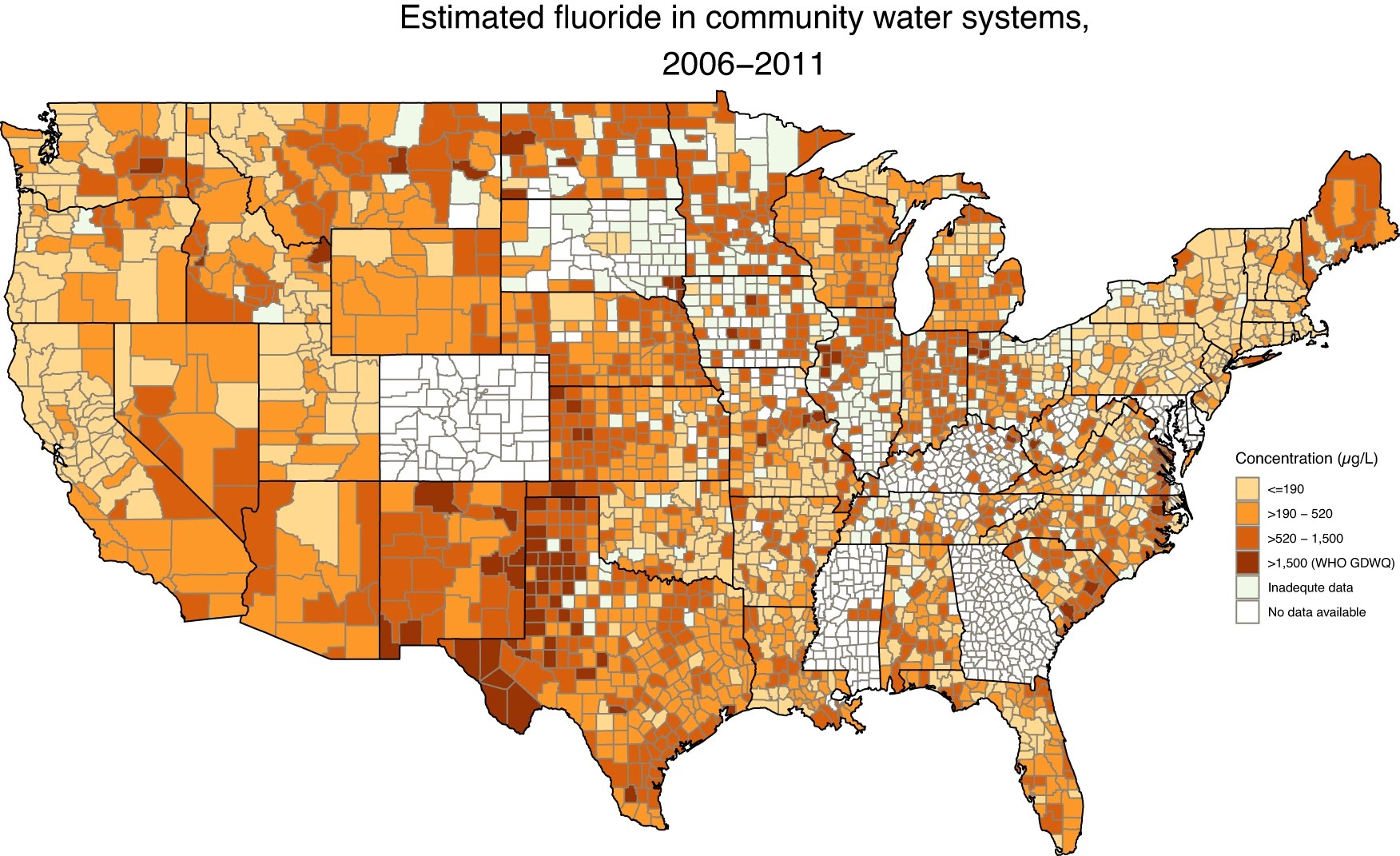

For reference: Only about 2.9 million people (~4.5 percent of those connected to public water supplies) in the U.S. receive municipal tap water with fluoride levels at or above 1.5 mL/L, according to a 2023 analysis. That number includes both those served by public water districts that fluoridate, and those that simply have naturally present fluoride in the water. In contrast, more than 60 million people in the U.S. still receive public drinking water containing lead levels higher than 5 parts per billion, when the EPA has concluded there is no safe amount of exposure, per a 2021 assessment from the National Resources Defense Council.

“Should Utah have taken fluoride out of the water? It’s a nuanced answer,” Bucher says.

He agrees that fluoride has benefits for oral health, and that the potential cognitive risks of fluoride in drinking water are not straightforward or well-established at low levels. In his view, emerging research warrants re-evaluating the recommended 0.7 level for community water fluoridation. He also says that, ideally, pregnant women and parents mixing infant formula should be granted access to non-fluoridated water at no cost. Though, Meyer counters that fluoride is important for the oral health of pregnant women, who are at increased risk of gum disease and cavities.

Further, not everyone is convinced by the findings the review did report. None of the 74 studies considered in the review were from the U.S. Over half were from China, where the context of fluoride exposure differs greatly from the U.S. Fluoride content is high in much of China’s regional bedrock, and fluoride levels are additionally inflated in the soil and water in part as a byproduct of coal pollution. Both highly mineral-rich bedrock and coal burning can bring along other contaminants, like arsenic, that aren’t necessarily controlled for in fluoride research. Most of the studies looked at exposure levels greater than 2 mg/L, and 52 of the studies were rated as having a high-risk of bias, by Bucher’s and his colleagues’ own classification.

Three Canadian studies included in the analysis offer the closest proxy for U.S. fluoride exposure, says Bucher. These studies assessed comparable levels of water fluoridation as exists in the U.S., and found some small associations between fluoridation and IQ losses among certain cohorts. However, all three of these studies come from a closely affiliated group of researchers, are based on the same dataset tracking maternal health, and use contentious measures of both IQ and fluoride exposure.

IQ tests for young children are usually administered by trained psychologists, not research assistants as they were in the Canadian studies, notes Tomar. And in utero and infancy fluoride exposure levels were estimated based off of a few, point-in-time maternal urine samples. Fluoride urine levels vary widely throughout the day depending on hydration level, diet, as well as factors like whether a person has just brushed their teeth or drank a cup of tea, says F. Perry Wilson, a physician and professor of public health and medicine at Yale University.

Moreover, the level of fluoride excreted in the urine at any given point doesn’t necessarily reflect the level in the blood–which is what would actually directly determine a fetus’ exposure, Wilson explains. Urine pH changes how much fluoride is peed out at any given time. Urine fluoride can vary even as blood fluoride level stays exactly the same, he says. A better alternative would be to directly measure blood fluoride, or at least collect 24-hour urine samples to minimize the impact of time of day. None of the 74 studies included in the analysis did so.

Other recent research, including a 2024 study from Australia has found no association between childhood IQ and fluoride exposure level. This research wasn’t included in the meta-analysis because it was published too recently, notes Bucher. Studies from New Zealand, Sweden, and elsewhere have come to similar conclusions, finding no negative effect of low levels of fluoride on IQ.

“The quality of a meta analysis is a function of the average quality of the included studies,” Wilson says. “I’m not saying the studies are [all] wrong, but when we evaluate the strength of evidence, we have to look at the quality of measurement.”

In his view, the evidence for neurological harm is weak. “It’s certainly something that could be studied more intensively, but I wouldn’t broadly change policy until we actually know what we’re dealing with,” Wilson adds, because the harms of ending fluoridation are so well understood.

[ Related: The shaky science behind treating measles with vitamin A. ]

Cognitive interventions that really work

It’s easy to understand why, given even the slightest possibility of cognitive losses, some may be uneasy about water fluoridation. If you have the means, cavities can be filled and forgotten about. But theoretical developmental impacts could last a lifetime. For pregnant women, parents wary of the potential effects of fluoride, or for those living in areas with especially high fluoride drinking water levels, bottled water and certain filters can offer alternative, unfluoridated sources.

Yet if the concern is truly the loss of a few IQ points, perhaps those advocating against fluoride would be better off focusing their time and resources elsewhere, suggests Wilson. The links between fluoride exposure and IQ losses are only correlations. But there’s a proven, causal method for boosting performance on intelligence tests: high quality education. Training children in creative problem solving boosts IQ scores by as much as 15 points, per one study of Eastern European children. Every year of additional schooling confers a boost of up to 5 IQ points, according to a 2018 global meta-analysis.

To Wilson, it feels “a little disingenuous when politicians pull their hair out and say, ‘won’t someone think of the children,’ when we have interventions in our back pocket that would more than outweigh any potential adverse effects of fluoridation.”

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.