Rubbing a black snail on a wart and impailing the creature with a thorn will make the bumps go away. Giving a donkey some bread will treat whooping cough. Mumps can be cured if you rub your head on the back of a pig. They may sound a bit strange now, but folk remedies like these are an important part of human history. Folk treatments can help explain more about everyday life in the past and how belief systems evolve.

In rural Ireland, using pigs to cure mumps and snails for warts are just some of the hundreds of remedies once believed to be cures. To learn more, a team from Brunel University of London combed through a rare archive of 3,655 folk cures first collected in the 1930s in order to test an anthropological theory: People are more likely to turn to religious or supernatural remedies when the cause of the illness is vague. Their findings are detailed in a study published this week in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

Building a folklore archive

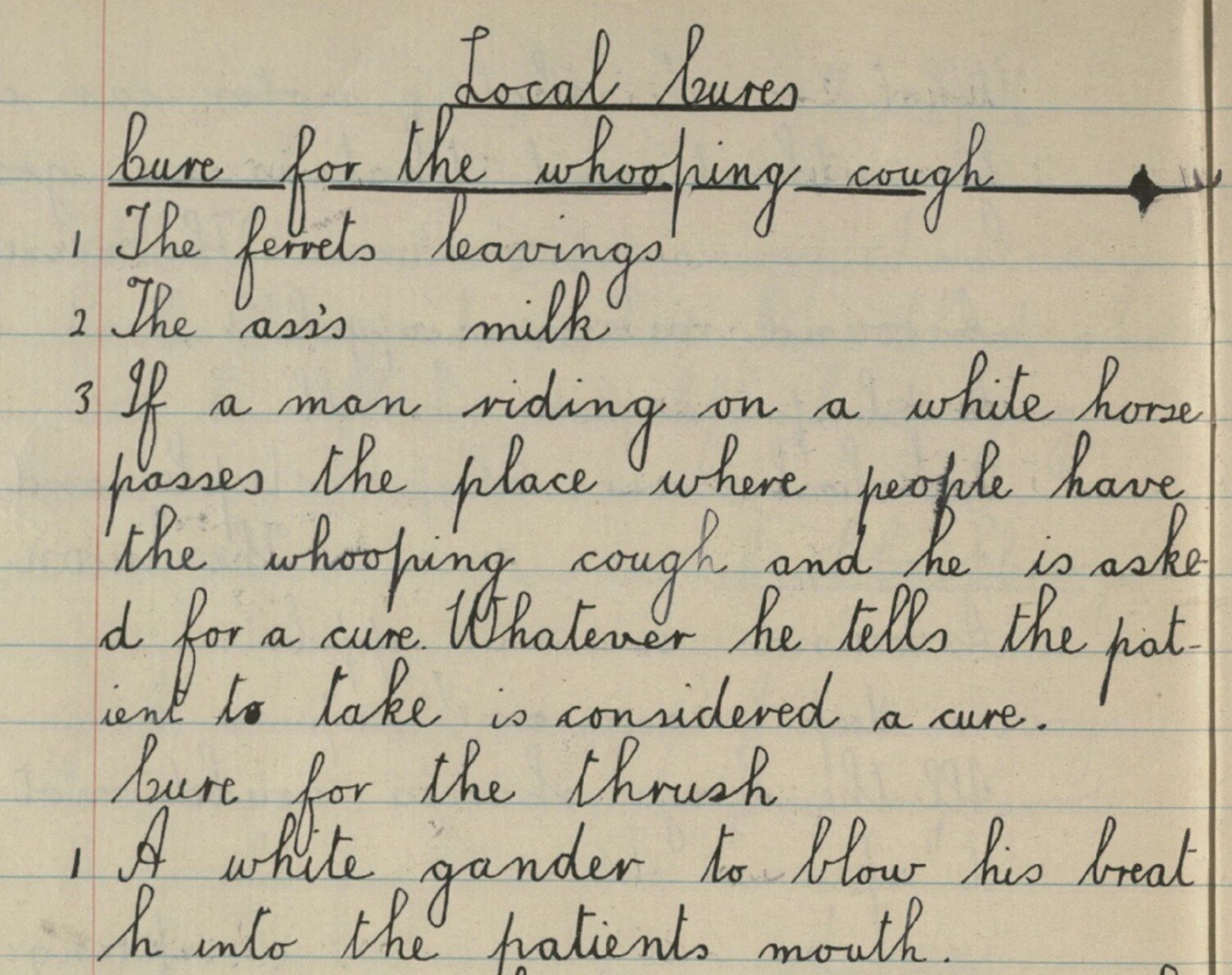

In 1937, the Irish Folklore Commission began a project to document and collect forgotten Irish lore with the help of some young researchers. Partnering with the Irish Department of Education, the commission asked primary school students to document the folklore in their own communities. About 50,000 schoolchildren were given notebooks and asked to interview their parents, grandparents, and neighbors all about local history, beliefs, and cures.

“You’ve got kids going and interviewing older people,” Dr. Mícheál de Barra, a study co-author and psychologist said in a statement. “Then these notebooks were brought back and transcribed by the teachers… and they were recently digitized. It’s a real kind of treasure trove.”

The children ended up collecting stories of folklife spanning 55 topics covering everything from how butter was churned to games to the devastating impacts of the Irish famine and sectarian violence. They wrote down these remedies in both Irish and English and gathered almost three-quarters of a million pages’ worth of documentation.

‘These weren’t random traditions’

In this new study, the team focused on 35 diseases. “We wanted to know whether the logic of folk medicine followed psychological patterns and it does,” said de Barra. “The more uncertain or mysterious the illness, the more likely the cure involved magic or religion.”

They asked two doctors to rate each of these 35 diseases according to how understandable it would have seemed to a common person at the time, in terms of what caused the illness, and what was happening in the body. Obvious cases such as cuts and sprains were marked as certain. Conditions like tuberculosis, warts, or epilepsy were labeled more mysterious.

“We find that diseases with uncertain causes were about 50% more likely to attract religious or magical treatments,” added study co-author and psychologist Dr. Ayana Willard.

Infectious diseases including mumps, whooping cough, and scrofula (a neck swelling, often caused by tuberculosis) are more frequently associated with supernatural cures. This could be because illnesses with unclear causes like these do not leave many obvious ways to act or intervene.

As far as cures, treatments range from religious actions—prayers over bleeding wounds, holy wells, and sacred stones—to more magical methods. One particular remedy instructed parents to place a sick child under a donkey three times and then feed them bread that was first breathed on by the donkey. Another cure claimed that a seventh son could heal anything, as long as a worm had been placed in his infant hand and was held there until it died.

“These weren’t random traditions,” said de Barra. “They reflected people’s need to understand and influence their health, especially when real answers weren’t available.”

The need for a solution

This study builds on earlier anthropology research that found ritual behavior flourished under uncertainty, such as fishermen saying prayers when heading into dangerous seas. In these often frightening situations, the team argues that belief systems fill in gaps when nothing quite explains what is going on around us. While these beliefs are rooted in history and may seem quaint by modern standards, the team feels that they can still apply.

“It’s pretty unsatisfying just not having a solution of any form,” said de Barra. “When there aren’t particularly good medical solutions, I expect people will keep searching for something that makes sense.”

In future work, the team hopes to examine the geographic spread of these beliefs using the original school records from the districts that participated in the Irish Folklore Commission’s project to trace how folk medicine traveled, clustered, or faded away.

“This is such a rich resource and there’s still more to uncover,” said de Barra.